Asha Herton-Crabb, a PhD student in the Department of International Relations, argues that for Trade and Gender initiatives (TGI) to take seriously the impacts of trade on women and non-binary people, they must look more broadly at the history of the trading system, the liberal ideas that imbue it, and the economic inequalities that sustain it.

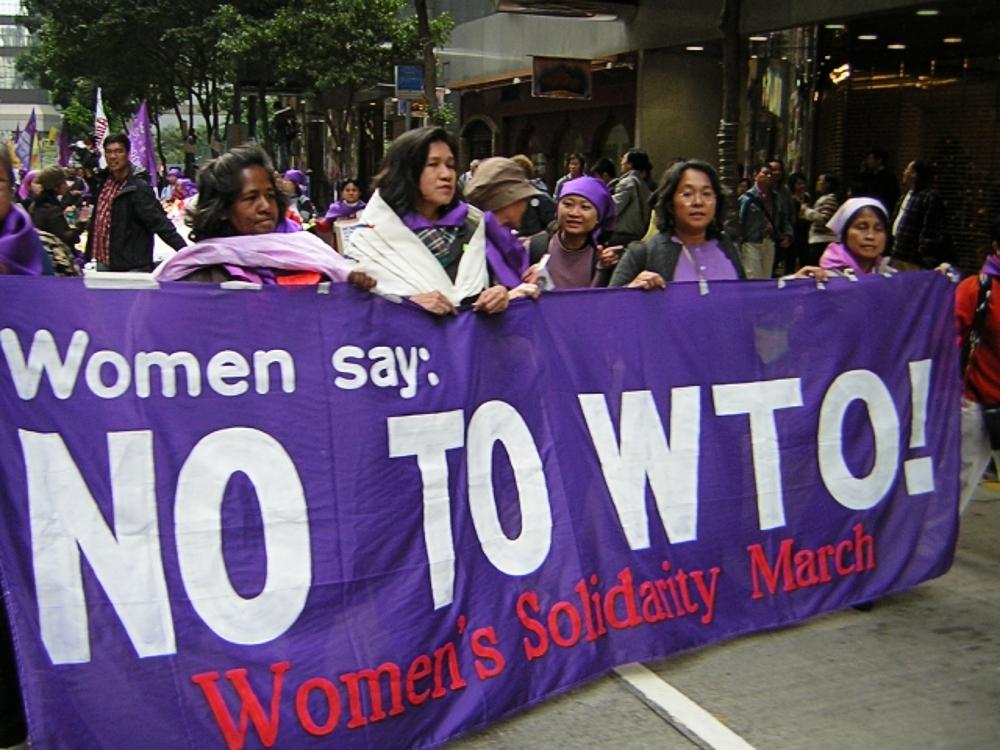

This week, the World Trade Organization (WTO) is hosting its first international research conference on trade and gender. The World Trade Congress on Gender is intended to be a space for “innovative thinking” and the sharing of research from around the world on gender and trade. For decades, the need to attend to the gendered impacts of trade has been recognised by feminist economists and activists around the world.

Yet, there are significant shortcomings to both the WTO’s approach and the bilateral trade negotiations it appears to be learning from. Alongside the many feminist critiques, I argue that for Trade and Gender initiatives (TGI) to take seriously the impacts of trade on women and non-binary people, they must look more broadly at the history of the trading system, the liberal ideas that imbue it, and the economic inequalities that sustain it. Until we start to think beyond borders, to unpack the inequalities between the richest white men and the poorest peasant or Indigenous women and non-binary people, TGI will remain window-dressing, devoid of the transformative, feminist potential that willed them into being.

Until we start to think beyond borders, to unpack the inequalities between the richest white men and the poorest peasant or Indigenous women and non-binary people, Trade and Gender Initiatives will remain window-dressing, devoid of the transformative, feminist potential that willed them into being.

The WTO has moved in concert with its member states and their bilateral agreements in the acknowledgement of the gendered impacts of trade. In 2016, the Chile-Uruguay free trade agreement was the first to include a standalone gender chapter; in 2017, the WTO published its Buenos Aires Declaration on Women’s Economic Empowerment and in 2019 WTO created its first training module on gender and trade.

And yet, both feminist activists and scholars have highlighted the ways in which TGI are ‘gender-washing’ global trade negotiations by focusing on women as export entrepreneurs at the expense of a more holistic and feminist approach to trade that could work towards benefiting the world’s poorest women. For example, the WTO’s Buenos Aires Declaration was met with considerable resistance from over 160 women’s rights and ally organisations who critiqued the Declaration as gender-washing WTO’s role in “deepening inequality and exploitation” globally.

The WTO’s bread and butter policies are harmful for women on a manner of fronts: trade liberalisation through tariff reduction and removal restricts government funds to provide public services, on which women and non-binary people are most reliant; growing food for export leads to land grabs, displacing local people and local production in places where women small holder farmers predominate; expanded intellectual property rights prevent the sharing of seeds critical for these women farmers. TGI tend to focus almost exclusively on women as export entrepreneurs with only minimal reference to women as workers, and a fleeting nod to unpaid care work. Resoundingly, the emphasis on women is limited to their potential contribution to economic growth, rather than the fulfilment of their human rights. Indeed, there is “little to suggest it will bring about fundamental transformations … [for] the world’s most vulnerable people”.

The emphasis on women is limited to their potential contribution to economic growth, rather than the fulfilment of their human rights.

A significant reason for these limitations is the classical liberal assumption that free trade will ‘lift all boats’ and provide well-being via the proxy of economic growth. The ideology behind TGI suggests that all that is required for gender equality in trade is to make some specific adjustments – affirmative action if you will – for women traders and other groups who are marginalised from world trade so that they too can participate more equally. Yet, trade’s ‘gender problem’ goes far beyond whether women and non-binary people are exporting at the same rate as men.

The logic of free trade, by Ricardo, Smith, and others, was informed by and used to justify Western European extraction and exploitation of its colonies and, in the case of Britain, its trading partners. The liberal theories of British imperialism were then embedded into the rules of economic domination through Anglo-American cooperation during the development of the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT), WTO’s precursor. Reciprocity and non-discrimination became key: principles based on the idea of equality which mask gross disparities between colonised and (settler-)coloniser states.[1]

If state-supported TGI really care about women then they must reckon with the fact that one of the greatest predictors of any person’s income is their nationality. This detail goes unrecognised when ‘gender equality’ is measured state by state. Inequality between states, and thus inequality between the richest men and the poorest women and non-binary people has become normalised and depoliticised through the use of language like ‘developed’ countries and ‘developing’ countries. When do we in wealthy, predominantly white (settler-)coloniser states stop to consider who developed who and the role that trade played in the process?

If state-supported TGI really care about women then they must reckon with the fact that one of the greatest predictors of any person’s income is their nationality.

Coloniality highlights how the modern world is constitutive of the imperial structures that developed through the onset of Western European colonialism in the 16th Century.[2] Coloniality thus facilitates a broader historical lens on the challenge of modern feminisms, to be not just intersectional but also anti-imperial: where, geographically, are the women most impacted by trade and how has history, politics, and imperial ideology impacted the power, wealth, and resources they have access to? Coloniality recognises the imperial, white supremacist, capitalist, and patriarchal structures that pervade the global political economy and the ideas we hold about what is ‘normal’ and ‘rational’. Importantly, coloniality emphasises the indivisibility of gender from other hierarchies such as race, class, and nationality: these intersections remain outside the purview of current TGI.

Coloniality thus facilitates a broader historical lens on the challenge of modern feminisms, to be not just intersectional but also anti-imperial.

What happens if we frame the intersection of Trade and Gender not as how to equalise women and men traders in their national contexts, but as a critical analysis of how trade has contributed to inequality between Indigenous women in the Brazilian Amazon and Jeff Bezos, or small-holder women farmers in rural Zimbabwe and Bill Gates?

TGI will continue to do little for the world’s most vulnerable people without confronting the question of how and why such disparities exist, but they’ll be able to pat themselves on the back as more women join the capitalist class as export entrepreneurs.

The situation is not, however, completely dire. It is impossible to deny the goodwill of the people engaged in TGI: their genuine desire to do better and be more inclusive is palpable even if their capacity to act beyond the ideational limits of trade liberalisation and Western classical economics is not. TGI are critical in highlighting to negotiators that not all people are equal when it comes to trade: that the principle of non-discrimination has its problems and serves to reinforce existing structural inequalities between men and women exporters. These initiatives have been vital for opening space among feminists to talk about and critique the impacts of trade on women such that these concerns are more likely to be taken seriously.

TGI are critical in highlighting to negotiators that not all people are equal when it comes to trade: that the principle of non-discrimination has its problems and serves to reinforce existing structural inequalities between men and women exporters.

There are many well-meaning and increasingly influential feminists driving this conversation in national and multilateral trade spaces. They can use their privilege to critically question the impacts of trade liberalisation on the world’s poorest women; to seek out and listen to these women and non-binary people where they are, rather than waiting for them to reach the table in Geneva, Ottawa, or Brussels; to search for alternatives such as a feminist re-visioning of the New International Economic Order. A feminist approach to trade must be holistic, seeking to understand and transform power hierarchies as has always been central to feminism’s political mission. We must take seriously the imperial dependencies inculcated into the global trading system. Such an approach would do more for the world’s poorest women than what TGI are currently achieving for a small group of women entrepreneurs.

A feminist approach to trade must be holistic, seeking to understand and transform power hierarchies as has always been central to feminism’s political mission.

[1] The WTO’s Generalised System of Preferences generously grants these previously colonised states a few extra years to liberalise but not the several hundred years of relative protectionism and an influx of cheap or slave-extracted commodities that imperial states themselves were granted

[2] To understand how Western European imperialism spread a particular understanding of gender as binary and hierarchical, see Lugones’ Heterosexualism and the Colonial/Modern Gender System.

This article represents the views of the author, and not the position of the Department of International Relations, nor of the London School of Economics.

Banner image by Puck Lo from IndyBay