Though female members of the Farc guerrilla movement face special barriers in their reintegration into wider society, the prominence of “insurgent feminism” within the peace process provides hope for the future, write Camille Boutron and Diana Gómez.

Though female members of the Farc guerrilla movement face special barriers in their reintegration into wider society, the prominence of “insurgent feminism” within the peace process provides hope for the future, write Camille Boutron and Diana Gómez.

• Disponible también en español

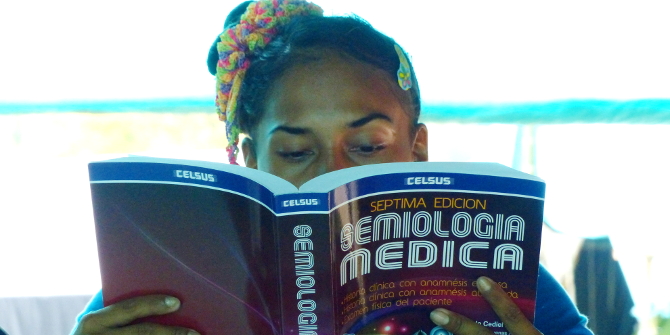

Last week on 1 March 2017, after half a century of conflict, Colombia’s Farc guerrillas began to disarm. Since last December, when they gathered in “concentration zones” dotted around the country, they have been preparing for reincorporation into civilian life. Some are studying to complete their secondary-level schooling with a view to entering higher education. Others are taking courses on subjects ranging from communication and social-media management to animal nutrition and nursing.

Although the Farc has agreed to abandon armed, subversive action, this does not mark the end of its political activity. Rather this activity will take new forms, including establishment of a political party. To this end, the group is training and organising particular cadres to go beyond concentration zones and deliver peace-education training as a first step towards entering the political realm. Reintegration to civilian life thus takes on social, human, and political dimensions, allowing for the emergence of new leaders, discourses, and proposals.

Around forty per cent of Farc insurgents are women and although their presence is visible throughout the group’s structure, the top echelons continue to be dominated by men. According to senior members, the influx of women began in the 1980s and picked up speed during the San Vicente del Caguán peace talks (1999-2002), where women took part in some committees yet remained absent from the negotiating table. But things changed significantly during the more recent Havana peace talks (2012-2016), with female Farc members playing active roles as negotiators, advisors, or spokespersons.

The most significant step towards acknowledgement of their issues and proposals was the creation of a Gender Sub-Commission in September 2014. This body, made up of five representatives of the Government and five from the Farc, allowed female members to gain public visibility, to spark debates on feminism and gender issues within the organisation, and to put forward proposals on reintegration into civilian life and on peacebuilding in general.

Although debates on gender equality were not new to the organisation, there had been a lack of spaces and mechanisms catering specifically to women’s issues, which made the new Gender Sub-Commission all the more important. Whereas other insurgencies, such as Peru’s Shining Path made women’s emancipation central place to their ideology in the 1980s and 1990s, the same cannot be said of the Farc. The creation of the Gender Sub-Commission was also facilitated by pressure from civil society and the international community. This pressure helped to open up debate on the specific experiences of women within the insurgency and allowed female leaders and ‘experts’ on gender issues (like Victoria Sandino) to rise through the Farc’s ranks, promoting dialogue both within the organisation and in the public sphere, even after peace talks had concluded.

Last month, for instance, female combatants in the concentration zone of La Elvira (Cauca) had the chance to discuss gender issues with international experts. This initiative reveals how gender issues can come to circulate amongst the peace process’ many distinct stakeholders, influencing the development of a politico-military organisation that had sometimes overlooked such issues.

But not all female Farc members are equally involved and many – especially amongst the rank-and-file – have not taken part in debates on gender, feminism and peacebuilding. Wider circulation of these ideas and issues could open up new possibilities for women within the organisation. Indeed, there is an urgent need for this to happen, as several studies have shown that the barriers to reintegration faced by former combatants are higher for women than for men.

Female combatants are often stigmatised for the double transgression of breaking not only the law, but also traditional gender stereotypes. Their suspected sexual promiscuity — or the belief that they may have suffered sexual violence — makes it more difficult for them to find partners, get married, and raise a family. Their reintegration into civilian life often requires them to accept roles that are traditionally assigned to women and often favoured by familial expectations and indeed public policies.

Although the government’s reintegration programmes do incorporate a gender perspective, they do so from a traditional, essentialist perspective that assumes women will “commit to build and promote family growth”. Women are thus led towards traditional, reproductive, subordinate roles, with their contribution to peacebuilding reduced to keeping their husbands away from guns. Women’s experience as combatants is still seen as exceptional and marked by victimhood rather than as an outcome of the characteristic frictions of societies in armed conflict, which themselves include a gender dimension. A supposedly flattering article published around Women’s Day last year under the title “From rifles to high-heels: Farc’s women in Cuba” was just another example of the dominant representations of former combatants that circulate in society. But the title begs the question of why these women, those not visible in Havana, should put down their rifles in such a conservative society? To pick up their aprons perhaps?

At a time when feminism has become the target of extreme and violent fascism, Colombian society must give these women the chance to put aside their rifles and continue developing into transformative political subjects outside the bounds of war. In order for this to happen the insurgent feminism of Farc leaders like Victoria Sandino and Manuela Marin must not only percolate into the day-to-day lives of female ex-combatants, but also engage with women’s and feminist movements in Colombia and beyond.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Images are not covered by the text’s Creative Commons licence (© 2017 Camille Boutron)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting