Multinational cooperation between Latin American dictatorships, particularly via Operation Condor, means that digital archiving of musical experiences under political detention must also take on an international dimension, write Katia Chornik and J. Patrice McSherry.

Multinational cooperation between Latin American dictatorships, particularly via Operation Condor, means that digital archiving of musical experiences under political detention must also take on an international dimension, write Katia Chornik and J. Patrice McSherry.

• Disponible también en español

Over 1,000 centres for political detention operated in Chile during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990). Music had a powerful impact in these places. For prisoners music was a source of resistance, inspiration, unity, solace, and solidarity. For agents of the state it served as a tool to indoctrinate, torture, and humiliate the imprisoned.

Thanks to the digital archive of Cantos Cautivos (Captive Songs), music is now also helping to recover this vital historical memory and provide public recognition, commemoration, and a measure of moral reparation to those who suffered terrible repression.

Thanks to the digital archive of Cantos Cautivos (Captive Songs), music is now also helping to recover this vital historical memory and provide public recognition, commemoration, and a measure of moral reparation to those who suffered terrible repression.

The archive represents the first online resource on music and political detention in Latin America, collecting testimonies of a wide variety of individual and collective musical experiences taking place at all levels of political imprisonment, from secret torture chambers to officially recognised prisons. Launched in collaboration with the Chilean Museum of Memory and Human Rights in 2015, it was originally available only in Spanish, but in 2016 the complete archive was also made available in English.

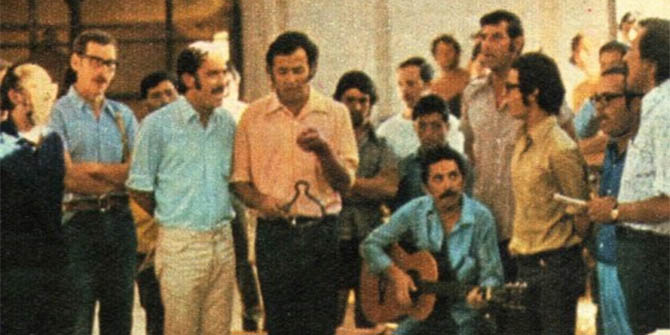

The largely crowdsourced content includes 130 testimonies relating to thirty political detention centres in Chile, of which approximately 30 per cent refer to songs partially or fully written under detention. Amongst the archive’s most unique materials are recordings by detainees at the Chacabuco concentration camp in the Atacama Desert and accounts of Dawson Island concentration camp at the southern tip of Patagonia. These invaluable accounts reveal the inner workings of a repressive state and the resilience of its political prisoners.

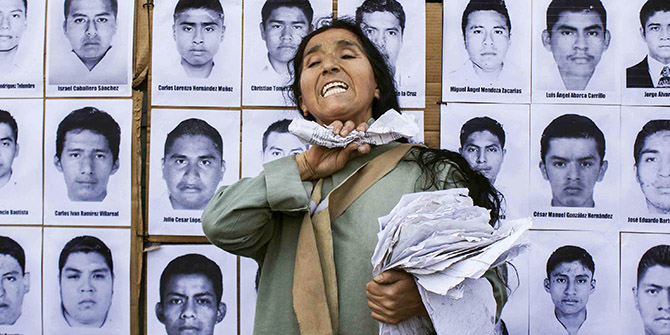

Luis Alfredo Muñoz González, detained in the notorious torture centre Cuatro Álamos in Santiago, recounts that “after our bodies have been destroyed to the marrow, when nothing is left of us but the murky eyes of death, music and song appear.” After a night of horror he hears a woman’s voice in another cell asking him to sing a song. She tells him she is Argentine.

He sings “Casida de las palomas oscuras” (Casida of the Dark Pigeons), a song composed and recorded by Spanish singer Paco Ibañez, with lyrics by renowned poet Federico García Lorca. She says she feels less alone. Surprisingly, he then hears a male voice from another cell, saying that the song was beautiful. The voice belongs to a European priest. The origins of both the cleric and the woman suggest that they may have been among the thousands of victims of Operation Condor.

Operation Condor was a secret, multinational “black operations” programme to destroy political opposition to the military dictatorships in Latin America. The system began in 1973-74 and was “institutionalised” in 1975. Organised by six Latin American states (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay) with secret backing from Washington, Condor operatives carried out covert abduction-disappearance across borders, targeting exiled political dissidents and activists fleeing the military regimes in their own countries.

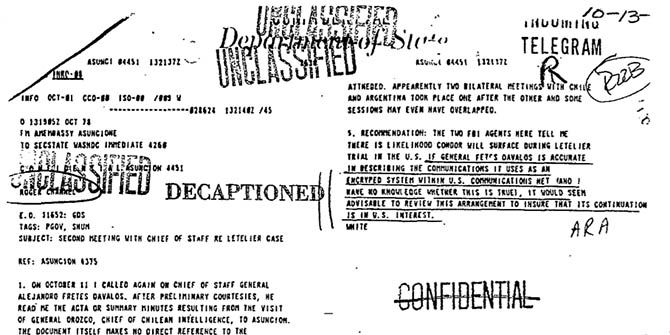

Condor’s methods were torture, extra-legal “rendition,” and extrajudicial execution. Special death squads also targeted leading opposition figures exiled in Latin America, Europe, and the United States. The notorious assassination of former Chilean minister Orlando Letelier and his colleague Ronni Moffitt in a 1976 car-bombing on the streets of Washington D.C. was a Condor operation.

Condor operated covertly within the hemispheric counterinsurgency regime heavily influenced by Washington. A declassified U.S. document, for example, shows that Washington authorised Condor agents’ use of “an encrypted system within the U.S. telecommunications net[work],” located at its major counterinsurgency base in the Panama Canal Zone, to “coordinate intelligence information” across the whole continent. This logistical support indicated deep U.S. knowledge of and collaboration with Condor.

Just as in Chile, there is evidence that music was used at Condor sites in other countries. In a recent email exchange, Sara Méndez, a Uruguayan woman imprisoned and tortured in the Argentine secret centre Orletti Motors (code-named OT-18 or “El Jardín” by military intelligence operatives), remembers no singing by the detainees. But she vividly recalls the use of music by their captors.

Méndez recounted that during torture sessions the abusers would play the radio loud to drown out the cries of the tortured. They would also laugh, mock, and taunt the prisoners, sometimes singing sarcastically themselves, changing the lyrics of songs in order to insult their victims or disparage organisations like Argentina’s urban guerrilla movement Montoneros, even if prisoners were not necessarily part of such groups.

One former Argentine political prisoner who spent years with other female detainees in Argentina’s Devoto Prison testifies that there was music among the prisoners there. In fact, there were even classes conducted by a fellow prisoner, who was a music teacher. “You don’t know how much I want to listen to music, to be tranquil, in silence, alone or with someone else, and to feel the sounds emanating from the loudspeakers…” wrote another detainee in a letter included in the testimonial book Nosotras, presas políticas: obra colectiva de 112 prisioneras políticas entre 1974 y 1983.

In Michael Chanan’s documentary Interrupted Memory, Ana Mohaded recounts another moving musical episode, when an imprisoned member of the well-known Uruguayan duo Los Olimareños sang a song heard by other detainees in San Martín Prison in Córdoba, Argentina.

The musician, Braulio López, sang to communicate his solidarity with the other detainees, he said. He was held in San Martín Prison as well as other political detention centres in Argentina. López’s case is believed to be a Condor operation.

As the links between Latin American dictatorships’ multinational cooperation, political detention and music have become clear, so too has the need for Cantos Cautivos to take on an international dimension. The archive is now looking to expand its database to include testimonies of musical experiences under political detention in other countries in the Americas, especially from those that formed part of Operation Condor.

The power of music to sustain and strengthen political prisoners in Latin America is a story that is only beginning to be written.

Notes:

• Visit the archive at www.cantoscautivos.org or follow on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Images used are not covered by the text’s Creative Commons licence

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting