Following a trial that lasted over three years, in May 2016 a federal criminal court in Buenos Aires convicted fifteen defendants for crimes against more than 100 victims of the infamous Operation Condor. For the first time, a court of law had recognised the existence of this transnational terror network, which was used to hunt down political opponents in South America in the 1970s. The ruling also saw the prosecution of state officials for human rights violations of a transnational nature. This historic trial offers important lessons that could help to achieve accountability for contemporary transnational human rights violations, writes Francesca Lessa (University of Oxford).

Following a trial that lasted over three years, in May 2016 a federal criminal court in Buenos Aires convicted fifteen defendants for crimes against more than 100 victims of the infamous Operation Condor. For the first time, a court of law had recognised the existence of this transnational terror network, which was used to hunt down political opponents in South America in the 1970s. The ruling also saw the prosecution of state officials for human rights violations of a transnational nature. This historic trial offers important lessons that could help to achieve accountability for contemporary transnational human rights violations, writes Francesca Lessa (University of Oxford).

Juan Hernández, Manuel Tamayo, and Luis Muñoz were three young members of the Chilean Socialist Party who, having fled persecution from the Pinochet dictatorship, sought refuge in the Argentine city of Mendoza in the mid 1970s. But with Argentina’s military coup in March 1976, the country became a death trap for them.

On 3 April, 1976, a joint Argentine-Chilean operation illegally detained the three exiles on Belgrano Avenue. After a brief spell in the military barracks in San Martín Park, Juan, Manuel, and Luis were transported back to Chile in a pick-up truck. There, survivors of the Cuatro Alamos and Villa Grimaldi detention centres recall seeing the three with clear signs of having suffered extensive torture.

More than forty years on, Juan, Luis, and Manuel remain disappeared, but after a relentless struggle by their families, Chilean courts did recently convict two members of the Chilean secret police over their kidnapping.

Understanding Operation Condor

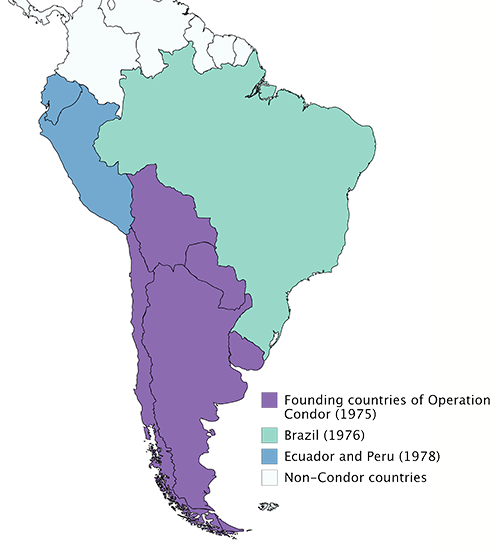

During the decades of state terror in South America between the 1960s and 1980s, stories like that of Juan, Luis, and Manuel were all too common. Within the geopolitical context of the global Cold War and the ideological influence of the National Security Doctrine, the dictatorial regimes of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay brutally repressed all forms of peaceful and violent political opposition.

Against this backdrop, thousands suffered the most serious violations of their basic human rights: extrajudicial executions, illegal detentions, enforced disappearances, and torture and inhumane treatment.

By the mid-1970s, political repression in this region had also acquired a sinister regional dimension through Operation Condor. This secret transnational collaboration between the region’s dictatorships was established in late November 1975 and reproduced the same kinds of atrocities on a regional scale.

As part of my research, I have been building a new database to record victims of transnational human rights violations in South America. Though still a work in progress, the database already holds 496 confirmed cases of victims between 1969 and 1981.

The majority (247) were Uruguayan (50%), 94 were Chilean (19%), 82 were Argentine (16%), 28 were Paraguayan, 13 were Peruvian, 18 were Brazilian, five were Bolivian, and nine came from the US and Europe (see below).

Operation Condor specifically targeted exiled political and social militants like Juan, Manuel, and Luis through a coordinated system of regional monitoring, intelligence, joint operations, secret detention and interrogation under torture, and often clandestine rendition to the country of origin, where targets would be disappeared.

Operation Condor on trial

The Argentine trial dates back to the years of impunity in South America in the 1990s. Six women who were relatives of victims filed the case in Buenos Aires in November 1999 with the support of two human rights lawyers. By 2013, when it finally reached the trial phase, it had expanded significantly in terms both of defendants and of victims. The case was built around a selection of over 100 victims whose experiences could provide a representative insight into Operation Condor’s activities.

The charges included illegal detentions and torture, while the overarching system of transnational political repression was deemed to constitute asociación ilícita, which is similar to the crime of conspiracy under UK and US law. The probing of the illustrative cases allowed state prosecutors to demonstrate that these were not isolated incidents but rather a systematic pattern of human rights violations perpetrated in a similar and coordinated manner across the region.

The Argentine prosecutors, judges, and defence had to explore an unprecedented abundance of evidence, including over 200 testimonies from survivors and experts, thousands of pages of archival records received from neighbouring countries and the US, as well as prior jurisprudence from Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

After 38 months of public hearings – and almost 17 years after the lawsuit was originally filed in 1999 – the court handed down its verdict before an audience of hundreds, with survivors and victims’ relatives crowding the courtroom in Buenos Aires (left). Many more watched on via livestreams at Argentine consulates in Santiago, Asunción, La Paz, and Montevideo.

Achieving justice for transnational crimes

The judges found 15 of the 17 defendants guilty, with sentences ranging from eight to 25 years. Those convicted included high-ranking politicians and officials like former Argentine dictator Reynaldo Bignone and the Uruguayan coronel Manuel Cordero, extradited from Brazil in 2010 to face this trial. The judges unquestionably affirmed that Operation Condor had constituted a transnational asociación ilícita.

Never before had a court recognised that a conspiracy had existed at the international level in order to coordinate persecution of political opponents all across South America.

By using emblematic cases, the judges were able not only to probe dynamics and responsibilities relating to each individual victim, but also effectively to try Operation Condor in its entirety. Indeed, these cases allowed the court to explore the ways in which the transnational terror network as a whole operated in practice. This meant that beyond the charges of illegal arrests and torture, the tribunal was able to assert that the machinery of regional repression had constituted a transnational criminal conspiracy devised by South America’s dictators to eliminate any form of opposition.

Over forty years on from Operation Condor, and largely owing to the tenacious and persistent efforts of survivors, relatives, and human rights activists and their lawyers, a measure of justice was finally achieved.

Beyond Operation Condor, this landmark trial provides four lessons that might apply to other contemporary manifestations of transnational human rights violations, including the trafficking of women, children, and migrants or the extraordinary rendition of alleged terrorists.

First, domestic courts can effectively probe transnational human rights violations. This is in line with the complementarity principle of the International Criminal Court, whereby the latter can step in if national jurisdictions are unable or unwilling to fully investigate and prosecute atrocities.

Second, tribunals can rely upon different jurisdictional principles – territoriality, nationality, passive personality, universality – to investigate cross-border crimes. There is no specific prescription in this regard, but varying combinations can be adopted in line with the circumstances and nature of a given situation.

Third, international cooperation between judges, lawyers, prosecutors, and human rights activists in gathering the necessary evidence is a crucial precondition for the success of such investigations.

Fourth and finally, state borders should not be seen as insurmountable obstacles in situations of transnational human rights violations. The Argentine Operation Condor trial has demonstrated that state agents can be held responsible for perpetrating human rights crimes outside of their own national territories.

Scholars and policy-makers working on the many manifestations of transnational crime can draw hope and insight from such cases as they seek to help victims achieve accountability for the horrors that they have suffered.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or LSE

• This post draws on the author’s article “Operation Condor on Trial: Justice for Transnational Human Rights Crimes in South America” (Journal of Latin American Studies, 2019).

• Featured image credit: Carlos Teixedor Cadenas, CC BY-SA 4.0

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting