Any attempt to increase Latin America’s productivity should adapt managerial ideas to the Latin American character rather than the other way around, argues Alfredo Behrens (FIA Business School, São Paulo).

Any attempt to increase Latin America’s productivity should adapt managerial ideas to the Latin American character rather than the other way around, argues Alfredo Behrens (FIA Business School, São Paulo).

There are many explanations for why Latin America has lagged behind regional leader the United States for over a century.

One might point to our recurrent macroeconomic crises, our lower educational level, and our poorer health services. Then there are the poor credit facilities, deficient infrastructure, and weak institutions foregrounded by economists. But these are not explanations but rather expressions of poor productivity, which relates to the way we are organised for work in the broadest sense: the geographical distribution of our populations, huddled in a few large cities along the coastlines; the disenfranchisement of large segments of our population, and the consequent lack of sense of social integration and common good.

Piecemeal approaches aiming to enhance the effectiveness of public policies, improve the supply of credit, or better understand the world of the shantytown will not be enough to address these problems, as their failure throughout the past century has already demonstrated.

A continent in search of a script

I will offer a complementary interpretation: Latin Americans fit poorly into the prevailing managerial script. That is, we are not suited to working in the way that we are expected to go about it. Consequently, our productivity suffers, and the meagre and poorly distributed surplus that results means there’s not enough to go around.

Latin Americans are akin to the eponymous “Six Characters in Search of an Author” in Luigi Pirandello’s famous play, desperate to burst into life by finding their place in the narrative but ultimately finding themselves orphaned and frustrated. In Latin America we are in search not only of leaders, but also of a script.

But the script to which we are accustomed and which we would like to follow is no longer available in mainstream business, leaving us at a loss when faced with a script that is entirely unsuited to our mindset.

Contrary to the standard view, I suggest that because mindsets take so very long to change, any attempt to increase our productivity should adapt this managerial script to the Latin American character rather than the other way around.

The rise and incompatibility of the American management script

Today the dominant managerial script is distinctly American, having spilled over into Latin America via John F. Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress during the Cold War, with American professors midwifing local business schools that taught in English. This strategy helped to create a local comprador class – sharing the interests of foreign investors, multinational corporations, and even militaries – that still prevails in modern-day Latin America and continues to provide the bulk of local management leaders. But this American script is predicated on goal-seeking, autonomous individuals rather than the journey-focused, group-orientated peoples found in Latin America.

Thus, in American narratives it is mostly about reaching a goal in the fastest and most efficient way. From a very young age, Americans are presented with clearly defined means and ends that are inflected with a strong dose of pragmatism, whether in Melville’s Moby Dick, where Captain Ahab’s “path to my fixed purpose is laid with iron rails, whereon my soul is grooved to run”, or in Warner Brothers’ Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner, where neither predator nor prey can exceed the limits of their shared route.

Iconic Latin American stories are markedly different, born of a feudal past: they stress adventure, heroism, or even public service, but rarely private gain (which is more usually disparaged). Thus, Miguel de Cervantes’ “Don Quixote” roams the Iberian peninsula righting wrongs, while Luis de Camões’ “Os Lusíadas” condemns the accumulation of material wealth and exalts expeditionary adventures that spread the word of Christ.

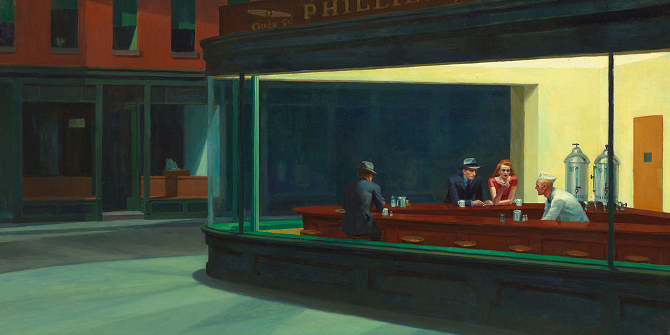

Latin American cultures are also significantly different from that of the United States. Narratives from the region like José Enrique Rodó’s “Ariel” denounced North American pragmatism, whereas José Hernández’ “Martin Fierro” in the mid-19th century or Juan Rulfo’s “Pedro Páramo” a century later repeatedly stressed the importance of group belonging. Likewise we see this group orientation in the crowds painted by Mexico’s muralists, Brazil’s Candido Portinari, or Argentina’s Antonio Berni. In the US, meanwhile, we find the bleakness of American solitude in works like Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks” and Andrew Wyeth’s “Christina’s World”.

Dancing in someone else’s shoes?

In Latin America gravitating towards family for longer periods generates distrust of outsiders and a preference for working with people you already know, as opposed to hiring impersonally from the market as mainstream management recommends. This relates to our corporations’ inability to grow and our universities’ failure to recruit or promote by meritocratic standards. This has led to poor research and development within corporations, which are themselves largely disconnected from universities, favouring in turn a dependence on exports with low value-added. This dependence militates against any demand for skill upgrades, meaning that those of lower socio-economic status remain marginalised and disenfranchised.

If making the journey together is of such importance to Latin Americans, should we not be making this the core of our managerial focus? Does focusing on the individual goal not deprive us of an important source of motivation?

Think of a Brazilian samba school. Dancers dedicate a year of precious spare time to a world-class competition that brings little more than fifteen minutes of fame. Only the first top three samba schools from an earlier competition have a chance of winning the parade, but the remaining nine samba schools continue to compete nonetheless. It is not winning the parade that counts, nor can the year-long effort of gearing-up to the parade be compensated by the fleeting glory of parading for fifteen minutes. Working together year after year, however, turns the members of a samba school into a kind of extended family, offering a sense of belonging frequently lost in rural migrations to an uncertain urban setting.

Revolutionary alternatives

Because the American managerial script doesn’t gel with Latin American culture, foreign-appointed business leaders have little charisma – or whatever charisma they do have fails to tally with what local workers recognise as such. The resultant low productivity feeds noxious political consequences like deep social frustration, feeble institutions, rampant corruption, and widespread violence.

The Latin American insurrections I studied for “Gaucho Dialogues on Leadership and Management” reveal that popular leaders had to recruit and reward in a different way, turning to family connections and rewarding collaborators with titles because money was scarce.

All across Latin America I also found that recruitment favoured affinity over dexterity, as the latter could be improved on the go. Whether defending Montevideo during the Great Siege, fighting for the Federalist Riograndense Revolution in Brazil, marching for Venezuela’s Liberal Restoration, or winning the Mexico’s revolution, fighters were bound through webs of pre-existing loyalties. Leaders recruited teams, not individuals.

Loners did not have an easy time in these fighting packs, as the case of Mexico’s Felipe Ángeles demonstrates. Trained at France’s Saint-Cyr military academy, Ángeles led Mexico’s Colegio Militar, where he taught artillery, a skill which came in very handy for Villa at the battle of Zacatecas. Yet Ángeles was considered too “foreign” for either Pancho Villa or Emiliano Zapata to fully trust him.

Leaders also recruited where their message would be more amenable. Gumercindo Saraiva’s conservative movement in Brazil targeted the country’s hinterland, for example, because the urban environment was not as sympathetic to his royalist message.

Revolutions also offered better chances for quick promotions, whereas performance assessments were crystal clear and feedback was given on the spot. Everybody knew where they stood and why. This is what Latin Americans expect, but it cannot be delivered by foreign-appointed managers unsure of their support bases and bound to calendar-based performance assessments.

Today’s managers of multinational subsidiaries forget these lessons when they recruit from the market, selecting mostly English-speaking graduates from top-schools, only to offer them unattractive work and long waits for promotion.

Changing the script

And so we come back to the initial question: why is it that Latin America lags behind the USA?

Essentially, because we were led to believe that the American way is the only way to do business, even if it works very poorly for us. With productivity remaining stubbornly low there is not enough to go around, frustrating all but the best off.

And yet, there have been important autochthonous managerial successes. Besides samba schools, Brazil has Embraer, the leading mid-sized aircraft manufacturer and Vale, the leading mining company. Mexico boasts Cemex and Bimbo. But these are all examples of autochthonous management. Corporations like Embraer, Vale, and even Petrobras all began, expanded, and achieved world recognition as state-run corporations, where management was of the local benevolent paternalist style.

The time has come to create a new script, one that will allow Latin Americans to enjoy and excel at work as they do at samba schools. Higher productivity will follow, and so too will a better future.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This article draws on the author’s own Gaucho Dialogues on Leadership and Management (Anthem Press, 2017)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Professor Alfredo Behrens’s view point and strategic thinking to some of the world development shortcomings is very astute and out of the box. Very different indeed. It does not start from a rightist or military coup détat or a communist revolutionary movement. If I understood him right the needed change can come from peoples minds and the way they see themselves and the world around them as well as how they can turn things around to their own benefit in accordance with their own culture and ways. If you start changing things and ways at your own micro level (home, school, firm) so that you start seeing yourself making progress, chances are your neighbor will start doing the same and then at the macro level (society, town hall, government). Good thinking Alfredo! Thanks.

Thank you, Agostinho. You are right; listening to people is the best way. It might be tricky, though. If the questions are asked by management or a management-appointed mediator, “impression management” mode will kick in, and responses will likely be gauged to please the bosses. Yet, there is a way around this conundrum.

I suggest that in hierarchical societies, where people tend to be clannish and distrustful of outsiders, hiring should respect clans. This will bring into organizations teams that already pre-exist. They will have their own networks and trust-verification patterns. If alignment with the organizations ends is ensured, those clan-based teams will perform magnificently well. However, these organizations will require a high level of tunning into the local culture. This, for example, might imply respect for the elderly, less pragmatism and more idealism, as in lofty goals. This does not come easily to the “comprador class” individuals that multinationals tend to staff their subsidiaries with.

There is more like this in my earlier book “Culture and Management in the Americas,” Stanford University Press. Also, in “Gaucho Dialogues”, by Anthem Press, or in “A Pig in a Poke Management,” with Inês Medeiros, https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.22117.

Very well punctuated with good analogies over a vast theme that is clearly dominated by Professor Behrens.

Thanks Marcus, I’ve looked into this but as you say, it is a vast theme. Alone I can only paint with a large paint brush. In a team we could do more. We could go into greater details in Latin American cases, or we could extend the coverage further and suggest this might even be important to other regions of the world, namely countries who are also of collectivist orientation like many in the Middle East, Asia and Africa. I’ve done some work with colleagues in India, but none on China and the Russian Federation, to mention only the largest BRICs. If someone out there wishes to develop Master dissertations or even PhD ones I am game!