If Venezuela’s opposition really wants to remove Nicolas Maduro, it must unite behind renegade candidate Henri Falcon, writes Asa Cusack (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre).

If Venezuela’s opposition really wants to remove Nicolas Maduro, it must unite behind renegade candidate Henri Falcon, writes Asa Cusack (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre).

• n.b. republished courtesy of Al Jazeera; Creative Commons licence does not apply

Can anyone win in an illegitimate election? This is the big question in Venezuela today, as commentators and citizens alike debate whether to participate or abstain in upcoming elections, where one candidate, Henri Falcon, has defied the opposition coalition’s decision not to take part.

In short, the answer is “yes”. Paradoxically, the very lack of legitimacy that undermines these elections has also created the conditions for a viable candidate to garner broad support and unseat Nicolas Maduro. But for that to happen, the opposition Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD) must back Falcon, and begin to convince a desperate and disillusioned electorate that voting can make a real difference.

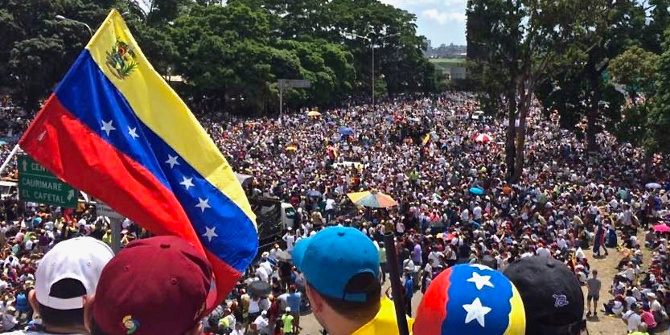

The most obvious reason why an opposition candidate can win is that, according to one of Venezuela’s most reliable pollsters, around 75 percent of those eligible to vote would be willing to vote against Maduro. Or to put it another way, “never, ever in the history of Chavismo over the last 20 years, has it been so clear that people want real change”.

Sadly, the complexity of this picture tends to be obscured by infantile narratives of opposition good guys versus government bad guys, where in reality the largest political group in Venezuela is the 51 percent supporting neither. Essentially, since the death of Chavez, most Venezuelans have been voting for the side they deemed to be the lesser of the two evils, but the cynicism and incompetence of both sides has gradually worn down even this minimal enthusiasm.

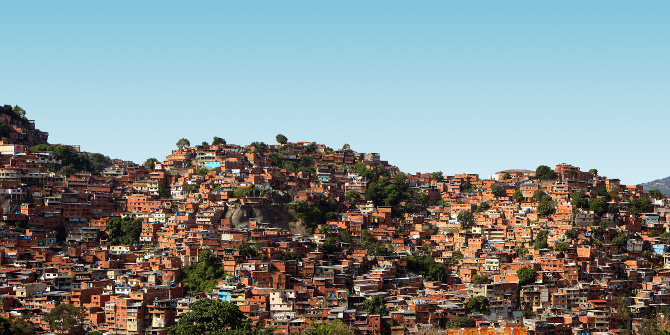

Support for Maduro has been ravaged by devastating economic, political, and social deterioration. Runaway inflation has eroded purchasing power and instilled a sense of intractable economic chaos. A dysfunctional currency regime has destroyed local industry, enabled massive corruption, and – combined with declining prices and production of oil – provoked serious scarcities of vital food and medicines. The resulting social hardship has fuelled unrest and emigration, but the conventional political channels for change have been blocked by anti-democratic means.

As for the opposition, no amount of hagiographic foreign journalism can erase what most Venezuelans already know:

- The MUD’s leaders are overwhelmingly drawn from the richer, whiter side of society and have never shown any sign of understanding or caring about the poorer, darker majority in the way that Chavez did.

- These leaders themselves have been all too willing to support anti-democratic measures, not least the 2002 coup and subsequent oil strike.

- Despite having nearly two decades in opposition to shape a coherent platform for government, they have never advanced beyond their one unifying goal of removing the incumbent.

As veteran pollster and analyst Luis Vicente Leon has noted, this opposition acts with all the self-obsessed short-sightedness of a teenager, and its leaders and parties inspire neither support nor sympathy.

Henri Falcon: traitor, Trojan horse, or potential president?

The key reason behind the MUD coalition’s decision not to participate in the upcoming elections was that two of its figureheads, Leopoldo Lopez and Henrique Capriles, are barred from running. Even without considering wider democratic failings, they are quite right to claim that this one fact makes the elections illegitimate. They are, however, quite wrong to think that the participation of one systematically disadvantaged candidate could lessen this illegitimacy, which is abundantly clear both at home and abroad.

Moreover, rather than being a traitor for deciding to run – or worse a Trojan horse for Chavismo – Falcon’s middle-ground status could prove more appealing than the usual MUD candidates to Venezuela’s unrepresented majority of disaffected “neither/nor” voters and disgruntled Chavistas.

Though opposition and government alike could depict him as a turncoat, this varied background means that he knows both sides of Venezuela’s stark political divide, has experience of public administration, and has already come close to engineering an opposition victory in far less favourable conditions (following Hugo Chavez’s death).

Since launching his campaign he has also made clear commitments that speak to public concerns: to tackle inflation through dollarisation, to reduce the potential for corruption by serving a single term, and to promote a peaceful transition both by releasing political prisoners and by disavowing persecution of Chavista officials. This moderate approach is strategic and pragmatic rather than moral or ideological, which is precisely what is required in a context of entrenched polarisation where the candidate could pick up support from all sides given the overwhelming unpopularity of his opponent.

Even without MUD backing, Falcon already leads Maduro by 16 points in head-to-head polling.

Hope, help, and turnout

But the real danger to Falcon’s bid – and the main reason that he needs MUD support – is that this election will be decided by turnout rather than voter preferences.

As it stands, only 41 percent of voters are “very willing” to vote – a figure usually around 70 percent at this stage – whereas a further 20 percent are “very unwilling”. Within the hard core of definite voters, Chavistas are significantly over-represented, whereas those determined not to vote are almost entirely opposition supporters.

If this situation prevails on election day – even more so if the opposition calls for a boycott – staunch Chavista voters will show up in the greatest numbers and return Maduro to the presidency with a low turnout. If, however, the opposition were to back Falcon or simply participation, a relatively modest 54 percent turnout could produce a Falcon victory.

MUD backing would also have an important effect on momentum and hope, particularly with election day over two months away. Though the MUD is far from representative of the entire opposition, its stance sets the tone for critical media that are far freer and more influential than commonly believed. And in Venezuela, this hope is more than a warm fuzzy feeling, as it can serve to assure Maduro voters direly dependent on the benefits of political patronage that supporting an alternative candidate represents a risk worth taking.

MUD backing is also crucial in terms of the final barrier to popular hope and participation: fear of electoral fraud. One of Falcon’s conditions for running was that the process would follow the same standards as 2012 and 2015 elections, with every step open to international observers. While the UN may not be able to send a full mission at such short notice, nor without a Security Council or General Assembly mandate, the key task of scrutinising storage and transfer protocols in Venezuela’s electronic system could be performed by a more specialised, lower-level mission. Paper copies deposited in ballot boxes for auditing of the electronic vote, meanwhile, could then be monitored by national observers. Again, the MUD has far more experience and manpower apt for this task than the smaller coalition behind Henri Falcon.

And if Falcon wins?

So, can anyone win in Venezuela’s illegitimate 2018 presidential election? The only answer is “yes”, but the possible gains depend on turnout, which in turn depends on whether the MUD calls for a boycott, participation, or support for Falcon.

While abstention offers nothing more than another round of violent and violently repressed street protests, devoid of any wider strategy, participation offers the chance for an unusually moderate, big-tent candidate to take the presidency, yet without whitewashing an election that is unquestionably illegitimate.

The greater the participation, the more likely such a victory becomes and the harder for the government to deny it. Maduro would either have to accept the result and give up power or force electoral authorities to commit out-and-out fraud of a kind not previously seen in Venezuela, thereby robbing his government of what little legitimacy remains.

Maduro’s incompetence and Falcon’s defiance have given the MUD leadership a better opportunity to defeat Chavismo than they ever managed to craft on their own. Now it’s up to them to take it.

• Read more from Asa Cusack

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• Originally published by Al Jazeera and republished with their permission; Creative Commons does not apply

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

A few years ago the opposition won the Assembly with the same CNE, so why couldn’t it happen again? I agree with your arguments and will vote for Henri Falcon. The worse possible strategy is to let Maduro win an election without a fight, at least make him sweat. Its an absurd strategy from the opposition that’s been influenced by extreme groups within. It is the time to vote and unseat a government that has only brought misery and anguish to its people. To wait and wish is not a strategy, the only action is to vote and massively. Will it happen, most likely not, unless the opposition individual leaders ask the people to vote. Capriles has a unique opportunity here to make a difference, asking to vote for Falcon.

Dear Dr Cusack,

I see your point about offering Maduro an easy way out, however, that argument completely ignores the elephant in the room: the illegitimate ANC.

The fact of the matter is, the role of President of the Republic has been usurped by the ANC. Therefore, any Presidential elections proposed by the ANC are merely a smokescreen. I appreciate that whilst your Spanish might be good, you may need to swot up on the intricacies of Venezuelan constitutional law.

To accept the ANC and any of its declarations is to effectively surrender the basis of Venezuelan law. What is most damaging to liberty and the rule of law in Venezuela is the illegitimate ANC.

From December 2015 onwards when MUD candidates won a majority in the Legislature elections, the PSUV increased its strategy of political aggression against legal norms and dissenters, a process which culminated in their illegitimate ANC inaugurated in 2017 after the deaths of at least 150 individuals who were enacting their constitutional right to protest against the regime.

Just like a pick-pocket seeks to distract their mark before committing their act, the Presidential elections are yet another distraction. The PSUV chose to drive themselves into a corner with their illegitimate ANC. Declaring Presidential elections amounts to, for lack of a better analogy, the PSUV painting a tunnel on the wall Wiley Coyote style to entrap the Venezuelan electorate (our figurative Roadrunner) as part in their continuing desire to remain in power, in a race between Chavista 1 and Chavista 2.

As a well read academic, my question to you is: if Falcón wins would his victory dissolve the ANC or are the elections yet another scheme to buy the regime more time to continue conducting their ‘socialist experiment’?

Thank you for your interest in Venezuelan politics.

P.S.: As your Spanish appears to be very good, if you have a spare moment I encourage you to listen to the following:

https://humanoderechorecords.bandcamp.com/album/rock-contra-la-dictadura-venezuela-volumen-01

Buenos días en Londres! Hemos leído atentamente su artículo reciente sobre las opciones electorales en Venezuela y observado la polémica que en español ha causado en su Twitter. Nos parece positivo y honesto de su parte el presentar ese análisis desde su particular punto de vista. Al respecto, nos gustaría saber si existe dentro del Instituto de Estudios latinoamericanos, con sede en Londres, una línea de investigación que este abierta a la participación de académicos venezolanos que deseen investigar sobre este tema? Si actualmente, no hay investigaciones sobre el caso Venezuela le sugerimos envíe alguno que desee indagar el proceso político tomando en cuenta la polarización e incluyendo la opinión de dirigentes como de simpatizantes o militantes de cada bando político. Eso sería muy interesante y objetivo. Presentaría una visión menos sesgada de la situación.

Por otro lado, lo invitamos a que se “reenamore de la revolución bolivariana” es un proceso político que da continuidad a nuestra historia como nación y que obviamentente va más allá de un presidente además, de que con sus errores y aciertos sigue siendo una alternativa a la globalization corporativa. Saludos, Dr. Asa nos agrada que haya vivido en VENEZUELA y maneje nuestro idioma.

Gracias por su preocupación por nuestro país.

Scarleth, te agradezco el comentario, sobre todo por este tono comprensivo que lamentablemente escuchamos cada vez menos al hablar de Venezuela.

Aqui en LSE no hay una linea de investigacion sobre Venezuela en especifico, pero habra seguramente muchas lineas que tocan temas relacionados o incorporan el caso venezolano para entender procesos sociales y politicos en un sentido mas amplio. Habra tambien investigadores en distintos departamentos que conocen el caso y que lo utilizan para fundamentar sus ideas. Aqui como en otras universidades del pais estamos siempre abiertos a la participacion de academicos internacionales, incluso venezolanos, aunque las posibilidades dependen mucho de los programas de investigacion e intercambio que financian los estados y los organismos internacionales.

Habiendo hecho trabajo de campo alli en que trataba de “tomar en cuenta la polarización e incluir la opinión de dirigentes como de simpatizantes o militantes de cada bando político”, te puedo decir que aun si quieres apartarte para tomar distancia, no es nada facil. Cada bando te quiere de su lado. Nadie quiere matices. En este ambiente de guerra continua, donde la meta parece ser destruir al otro, solo interesa lo que se pueda convertir en arma. Y por la misma razon ningun analista — aunque no tenga interes ni vinculo alguno — se toma en cuenta mas alla de cierto grupo de gente. Al contrario, una reaccion comun — lo veras en mi Twitter — es tratar de socavar a esta persona acusandole de haberse vendido a uno u otro bando.

El problema de base es que cada bando quiere ganar a todo costo aunque haga daño al sistema politico, a la sociedad, al pais. Hay una mayoria que no forma parte ni de un bando ni del otro, pero no tienen representacion clara en este momento y el sistema ofrece cada vez menos posibilidades de ofrecer esta representacion.

Buenas noches Dr. Asa. Muy complacida de haber podido participar en este espacio virtual. Nos han permitido publicar en nuestro idioma y han sido muy equilibrados al momento de considerar nuestro comentarios sobre su artículos. Nos agradecidos, por que usted ha respondido muy amablemente a nuestras inquietudes y ha sido una orientación muy valiosa. Aunque le reitero, nosotros los venezolanos estaríamos encantados de presentar trabajos de investigación que estuvieran insertos en una linea de investigación mas que partidista, consonantes con las necesidades de interés y conocimiento que debe haber en el mundo entero sobre las innovaciones en los sistemas políticos latinoamericanos y su impacto en la calidad de la democracia en un contexto post neoliberal. Actualmente, en la mayoría de los gobiernos del continente ha asumido el poder lideres con una tendencia ideológica de derecha y cuyas políticas están inscritas en la gobernaza empresarial. Sin embargo, se han incrementado los niveles de conflictividad social y organizaciones de todo tipo insisten en la lucha por la reivindicación de sus derechos y el mantenimiento de logros alcanzados. Entonces, investigar sobre estos temas nos parece mas que relevante. Ojala, así como usted lo dijo organismos internacionales tengan la apertura para financiar este tipo de trabajos académicos. Muchas gracias por su atención y amabilidad. Saludos, desde Venezuela, Scarleth Robles

Surprising the article doesn’t mention that if Chavismo were to lose power, almost all of the top gov’t officials, possibly along with the top military generals would go to jail (or worse).

For this reason even if the vote was 99% for the opposition, Chavismo would still stay in power by force (as they have been doing)

Therefore the MUD is smart to not give into these shame elections as they have a zero chance of winning and do nothing other then legitimize the elections.

Also this quote ” or force electoral authorities to commit out-and-out fraud of a kind not previously seen in Venezuela” Really? They have been committing massive fraud on an epic scale in all the elections of the last 2 years. The numbers for the municipal elections were pretty much pulled out of thin air.

I personally don’t believe in the idea that the Chavista government has any problem in committing massive fraud to cover up an election loss. Doesn’t matter if every single person votes for Falcon, those votes don’t count. The election is a total sham. If it came down to massive street protests and they have to quell it down by force, they already did it last year, they will have no problem doing it again. This illegtimate gov’t has already lose face years ago so to say they have a problem losing face by committing “out-and-out” fraud doesn’t hold weight. All of South America (except Bolivia) and the entire world already turned their backs on Venezuela. These criminals have everything to lose by allowing an opposition win.

I’ve seen some reports by some publications like Forbes hypothesizing that they will voluntarily give power to Falcon to negotiate a smooth transition and give them a “soft landing” while Falcon promises not to prosecute the former gov’t for their crimes. For anyone who believes that, keep dreaming.

Why do you think Maduro has been promoting anyone with a criminal history to the highest ranks? Drug trafficker as VP, convicted murdered on the supreme court etc etc.

The idea is by promoting these thugs and criminals with their known histories, they will be most unwilling to relinquish power and willingness to fight to the bitter end.

Playing along with the charade that there is still some “democracy” only strengthens this regime and for that reason I think Falcon was a fool to participate.

Fred, thanks for the detailed comment.

There is a hint at the military problem, but really it’s an issue of space. Al-Jazeera are relatively generous at 1200 words, and I was already closer to 1400. You could — and people do — write books about any aspect of this, but hardly anyone would read them, so I’m afraid some simplification is always going to be necessary if you want your message to have any impact.

The main thing I would say about the military aspect is that I am fully aware that Maduro surrounds himself with those who are most at risk of being prosecuted if he loses power. But that’s precisely why a political opponent needs to at least give some chance of an acceptable exit for those people (irrespective of the morality of it). That presents a possibility of positive progress, whereas baying for blood just reinforces their incentives to support Maduro. What is the point in this apart from satisfying (increasingly justifiable) anger? What is the plan? I don’t see one, and the MUD’s record suggests there is no reason to believe that they have one. All of the roads that this approach opens up are also less attractive than a peaceful handover of power, so even a slim chance of the latter should be seized upon.

On elections there is a huge “crying wolf” problem. Electoral conditions have been different at every stage, more so in the wider sense than in the technical, procedural one (until recently — see comment below). The opposition has been saying the system was rigged forever, even when it quite clearly was not. If I remember rightly, in the early days they were even criticised by foreign observers for scaremongering about the system. And of course they later used it themselves for primaries. Again, there’s nothing to be gained in making broad-brush, inaccurate claims about the system now or then. If there are possibilities for change due to particular aspects of the system or the wider conditions, then anyone wanting to actually deal with the reality should recognise and work with them. (The person who knows most about the system is Jennifer McCoy, and she took no issue with this aspect of my analysis when she recommended the article to her followers.)

Overall, it’s not that I’m saying this will definitely work, but it holds more hope than the dead end of abstention. And indeed the conditions in future elections are only likely to be worse if this chance is not taken (on which, see Victor Alvarez: http://panorama.com.ve/opinion/La-abstencion-solo-es-util-al-continuismo-gubernamental-por-Victor-Alvarez-20180327-0105.html)

Great points, but you forget that they are going to commit fraud like they did in the last election. And seriously? “robbing his government of what little legitimacy remains.” They have no legitimacy whatsoever.

Mila, thanks for the comment.

On the legitimacy point, it’s a very difficult thing to judge since it’s subjective, but I was suggesting that they have very little anyway.

On the fraud possibility, the previous manipulation of turnout seems to have been a political one rather than a technical one: the system counted the votes correctly, but the state announced an inflated figure (seemingly to outdo the opposition’s figure for turnout in the unofficial referendum on the constituent assembly). The exit of Smartmatic as a result of their declaration about this is a shame in this sense, as it leaves no one to vouch for the electronic side of the system. Hence I hoped the UN might send a smaller, more specialised mission for this purpose (UNASUR is not really geared up for observation; the OAS could seem partial given the over-zealousness of Almagro; the timeframe is probably too short for the EU leviathan, and they might also be seen as partial). But the physical side of the vote could be covered by national observers: making sure paper copies match electronic copies, taking copies of acts after individual polling stations close to compare with central results, preventing tampering with physical materials for auditing by physically accompanying them throughout the process. This is a big job, however, and the MUD would be much better placed to provide the human resources and know-how required.