While academic research recognises a number of potential drivers of Venezuela’s social and political polarisation, major English-language newspapers tend to depict Chavismo alone as responsible for tearing apart a supposedly peaceful and united nation, writes Alan MacLeod (Glasgow University Media Group).

While academic research recognises a number of potential drivers of Venezuela’s social and political polarisation, major English-language newspapers tend to depict Chavismo alone as responsible for tearing apart a supposedly peaceful and united nation, writes Alan MacLeod (Glasgow University Media Group).

Polarisation is a key issue in Venezuela. Rather late to the party, this month the United Nations noted its concern over the issue, but in reality Venezuela has been economically, socially, and politically polarised for decades.

The country’s experiment with neoliberalism in the 1980s and 1990s led to significant increases in inequality, poverty, and unemployment, which in turn raised the temperature in an already volatile political climate. The 1990s in particular was a decade marked by coups, impeachments, scandals, near-daily protests, and the rise and fall of several political parties, all of which fed into the surprise victory of the rank outsider Hugo Chávez in the 1998 presidential election.

Explaining polarisation

Despite these historical roots, the issue of polarisation only began to receive sustained attention after Chávez’s ascent to the presidency. Political scientists, historians, and Latin America specialists have identified four main sources of polarisation:

- Class hatred and conflict fomented by Chávez and his movement

- The actions of a disgruntled opposition that has consistently tried to oust the government by extralegal means

- US support for the 2002 coup, for the subsequent oil strike, and for radical political groups more broadly

- Reactionary and highly partisan local media that stir up tensions domestically

Yet, the latter three of these explanations and any hint of pre-Chávez polarisation are all but absent from accounts in Western media, where Venezuela is depicted as a once peaceful and united nation that has been torn apart by the rhetoric and policies of Chávez alone.

Polarisation through Western eyes

My recent research published in The Bulletin of Latin American Research analysed how polarisation has been represented in the Western media by sampling 381 articles from seven of the world’s most influential English-language newspapers during three key periods of the Chávez era (1998-2013):

- Newspapers

The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Miami Herald, The Guardian, The Times (London), The Daily Telegraph and The Independent - Key periods

The 1998-9 election and inauguration of Chávez, the 2002 coup, and finally Chávez’s death in 2013 plus the subsequent election of Nicolas Maduro

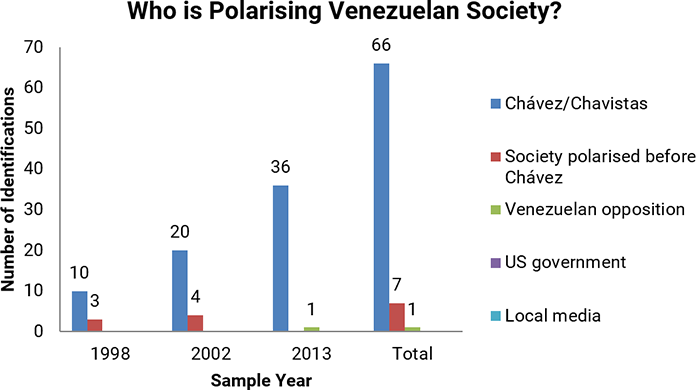

As illustrated below, within this sample there were 66 identifications which held Chávez or Chavismo responsible for polarising Venezuelan society, one relating to the local opposition’s divisive role, and none at all giving any role to the US government or the local media. There were seven references to the existence of social polarisation in the pre-Chávez era.

The devil in the detail

Even before he had been elected, the idea of Chávez as a threat to national unity had emerged. In its coverage of the 1998 election, The Miami Herald quoted one source as saying:

“There are two candidacies…one that divides Venezuelan society profoundly and dangerously [Chávez], and another that has enormous capacity to unite [his opponent].”

The Times, referencing Chávez’s role in a 1992 coup attempt, noted:

“Chavez’s presence on the political scene has deeply divided the country. ‘Once a coup leader, always a coup leader,’ argue upper and middle-class Venezuelans who fear his radical left-wing views and authoritarian manners.”

Yet, when the opposition themselves staged a momentarily successful coup in April 2002, there was no suggestion that this polarised the country. In fact, across 139 articles covering the coup, only Chávez was deemed responsible for polarising society. The Guardian reported that:

“Mr Chavez polarised the country by his attacks on the media and Roman Catholic church leaders, his refusal to consult with business chiefs and his failed attempt to assert control on the unions.”

At the same time, The Miami Herald published a story entitled “Chávez’s Return May Deepen Divisions”, in which it was claimed that:

“President Hugo Chavez’s astonishing survival of a coup attempt may only sharpen the class hatreds that are tearing Venezuela apart, analysts said Sunday… Venezuela’s current crisis is only partly political and largely the result of a class struggle seeded and nurtured by Chavez since his election in 1998.”

That is, there was no responsibility for generating polarisation amongst the opposition, the local media, or the US government, all of which backed the coup. Instead it was the coup’s target, Chávez himself, that caused the polarisation.

The Guardian is generally regarded as the most liberal or left-wing major newspaper in the Anglosphere, whereas The Miami Herald‘s take on Latin America is arch-conservative, with Miami’s significant ex-pat community exerting direct influence on the paper’s content. Yet, there are only minor differences in how Venezuela is represented in these publications, or indeed across the entire gamut of major newspapers, British and American, liberal or conservative.

American outlets cited Chávez or his movement as the cause of polarisation 42 times as compared to UK newspapers’ 24. Left-of-centre publications charged him with polarising society 35 times as compared to 31 times for right-of-centre outlets. However, when taking into account the greater number of American articles and the greater average length of liberal articles, the frequency of references to Chávez’s polarising influence was virtually identical whether publications were left- or right-wing, British or American.

Not only was frequency fairly uniform, there was also a distinctly similar tone across the board, as is clear from analysis of the many obituaries of Hugo Chávez following his death in 2013.

The New York Times stated that “Mr. Chávez mined and deepened the divide between the masses of Venezuela’s poor and the middle and upper classes, presiding over a bitterly divided country”, whereas The Guardian noted:

“The debate continued as to whether Chavez could fairly be described as a dictator, but a democrat he most certainly was not… he assiduously fomented class hatred and used his control of the judiciary to persecute and jail his political opponents, many of whom were forced into exile.”

Across 381 articles there is only one reference to a force other than Chavismo bearing any responsibility, with the Washington Post noting 52 lines into one story that:

“For chavistas – the diehard supporters of Chavez, who died after a long battle with cancer – the opposition is made up of people who are little more than American puppets solely interested in pillaging the country and keeping the poor down. ‘Chavez said, “No more. We’re all the same,” and that’s how the polarisation began,’ said Ismer Mota, a pro-government activist.”

Yet, this comes within an article whose sub-headline states that “Hugo Chavez polarized Venezuela but his people are more divided than ever” before going on to add that polarization was “a central strategy of Chavez.”

Thus, the one identification providing any sort of counter-balance to the dominant narrative of Chavismo as the sole driver of polarisation comes through quoting a supporter of someone the Post had regularly described as a “strongman”, a “dictator” and a “demagogue”, and even this was buried in an article that explicitly refuted that opinion.

Echoes of past portrayals of the Latin American left

This is hardly the first time that a leftist government in Latin American has overwhelmingly been portrayed as polarising. Nicaragua’s Sandinista government in the 1980s met the same fate, whereas The New York Times claimed shortly after the 1973 coup against Chile’s Salvador Allende that:

“No Chilean party or faction can escape some responsibility for the disaster, but a heavy share must be assigned to the unfortunate Dr. Allende himself. Even when the dangers of polarization had become unmistakably evident, he persisted in pushing a program of pervasive socialism for which he had no popular mandate.”

This strongly suggests that “polarising” has a political meaning to much of the English-language press, equating roughly to “governing in a way in which the West dislikes”. As such, any “polarising” government that achieves power quickly draws the ire not only of Western powers but also of the Western press.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• Draws on the author’s article Was Hugo Chávez to Blame? Media Depictions of Polarisation in Venezuela, 1998–2013 (2019)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

If supposed divisions in Venezuela and the consequent odium heaped upon the Chavista regime are artefacts of the Western press, prompted by “governing in a way in which the West dislikes”, maybe we should look to the Socialist International for a less biased opinion. In August 2017 it asserted:”The Socialist International strongly condemns the decision of the Venezuelan regime to usurp the powers of the National Assembly, the seat of the legislative power in that country. … Within this context, we also call on the Organisation of American States, OAS, to take immediate action in favour of the enforcement of the Democratic Charter in Venezuela.” http://www.socialistinternational.org/viewArticle.cfm?ArticleID=2528 .

This year it has recognised Juan Guaidó as interim president. The organization also expressed its “enormous concern for repression carried out by the “illegitimate regime of Nicolás Maduro” and “demands the full restitution of the constitutional order”. It sounds as though Venezuela is actually being governed in a way that most people, apart from thugs like Castro and Putin, “dislike”.

Since the author also suggests that criticism of the Nicaraguan government is misdirected, it’s worth noting that the SI expelled the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) last month. “The Council of the Socialist International meeting in the Dominican Republic has decided to expel the FSLN from the organization for the violations of Human Rights and the democratic values” committed by the Ortega regime in Nicaragua.

No, I’m afraid unsympathetic reporting is not the same as biased reporting. The trajectory of the Chávez regime became clear early this century, including the use it intended to make of class divisions. As government blunders multiplied exponentially, all were blamed on wicked “coupmongers” from the upper classes. Short of lavatory tissue? All the fault of CIA minions hiding the stuff. Unfortunately, this seems to have been swallowed by many political sympathisers abroad who became blinded to the true nature of the government. For example, I discussed the collapse of the politicised oil industry back in 2011 in the Madrid El Pais but it seems to have come as a bolt from the blue in some quarters: https://www.flickr.com/photos/94703479@N00/43180960612/in/album-72157668833746287/ .

A sample a few hundred articles on geophysics is likely to show a strong tendency to prefer a spherical rather than a flat model for the Earth. Can this be explained by factors other than blind, “Western” prejudice?