Human rights violations committed by Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship in Chile contributed to the electoral defeat that led to his downfall. Surprisingly, this happened without changing citizens’ political alignment, write María Angélica Bautista, Felipe González, Luis Martínez, Pablo Muñoz, and Mounu Prem.

• Disponible también en español

At any give time there are thousands of people being repressed and even murdered by authoritarian regimes around the world. Yet at the same time dictators are increasingly relying on elections to validate their rule. In a world where citizens are becoming ever freer to express their political preferences by voting, the important question is whether these acts of repression influence the chances of dictators remaining in power.

But the answer to this question is far from obvious. The state might use repression precisely to suppress opposition, but citizens also have the power to punish acts of the state, meaning repression has the potential to backfire.

Insights from Pinochet’s Chile

The regime led by General Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990) used military forces to murder more than 3,000 people. But then, exactly 30 years ago in 1988, Pinochet lost a referendum on continuation of his government, sparking Chile’s return to democracy.

Our latest research shows that state-led repression contributed to Pinochet losing that election because it triggered a social movement that craved a return to democracy. Yet, when democracy returned in 1990, those who were more exposed to violence were no more likely to support left- or right-wing candidates; they simply preferred democracy to dictatorship.

A network of military bases was key when Pinochet rose to power on 11 September 1973 via a coup against the socialist president Salvador Allende. From that day forward, places located near to the nodes of that network were more likely to be exposed to state violence.

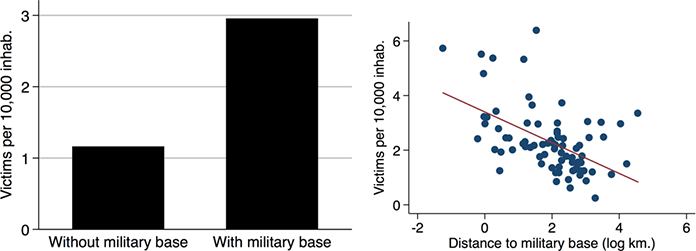

The location of military facilities – constructed anything up to a century earlier – was related to security concerns rather than the political alignment of citizens in the surrounding area. During the dictatorship, counties hosting a military base within their boundaries had more than twice the number of victims than counties without bases, irrespective of the makeup of their populations. And the chance of being a victim decreased with distance from these facilities (see figure 1, below).

Repression and Chile’s famous “No!”

The 1988 referendum on the continuation of Pinochet’s rule attracted a lot of attention in Chile and around the world. More than seven million people registered to vote, which is the highest tally in the country’s history. The political circumstances, together with international monitoring, also meant that this was a relatively free and competitive vote.

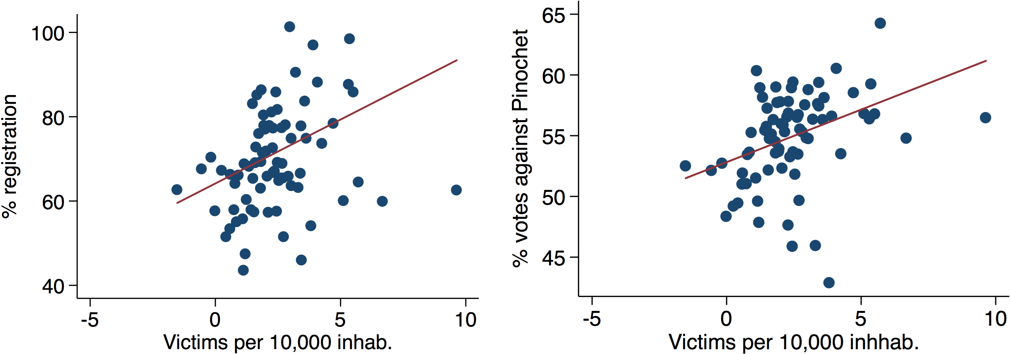

Notably, those places most exposed to violence also experienced the highest levels of voter registration. In addition, these places voted most strongly against Pinochet’s continuation in office (see figure 2, left panel, below). The share of voters supporting the “NO” option, which heralded Pinochet’s exit and new presidential elections open to all parties, was also higher in counties with more victims of the dictatorship (figure 2, right panel). Televised political campaigns to inform citizens about acts of repression also helped to stimulate the vote against Pinochet.

Understanding the local-level effects of repression on support for democracy

Local levels of state-led violence were an important factor behind people’s support for democracy for two different but related reasons.

First, the Pinochet regime went to significant lengths to minimise knowledge of repression. Examples abound, but the most common strategy was to manipulate the diffusion of information through newspapers and the television. This censorship made local events a critical source of information for communities. Second, personal experience motivates people more than the experience of others more distant in a social network. Both factors contribute to knowledge of repression irrespective of political alignment.

Pinochet led the country by forming a political coalition with right-wing parties, going on to implement wide-ranging economic and institutional policies, not least a new constitution in 1980. The existence of this alliance makes it logical to expect that acts of repression during these years might also have pushed citizens leftwards on the political spectrum.

However, our research also finds that this is not the case: places with higher levels of repression exhibit similar levels of support for left- and right-wing political candidates in each and every presidential and local election since the return to democracy. That is, state-led violence triggered a movement for democracy and a desire to end the authoritarian regime in charge without affecting people’s political alignments.

The experience of Pinochet’s military dictatorship thus provides an important lesson for other countries in Latin America and the rest of the world: rather than quelling dissent, acts of repression can create powerful social movements that crave a return to democracy. And as Chile’s case shows, they may well get it.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• This blog draws on the authors’ paper “The geography of repression and support for democracy: evidence from the Pinochet dictatorship”

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting