There is nothing new about Trump’s linkage of trade and non-trade issues, but subjecting trade deals like the North American Free Trade Agreement to the whims of the US president undermines a key benefit of such arrangements: greater stability. Without this stability dividend, potential partners could begin to question whether the costs of forging complex agreements with the US outweigh the benefits, writes Ken Shadlen (LSE International Development).

There is nothing new about Trump’s linkage of trade and non-trade issues, but subjecting trade deals like the North American Free Trade Agreement to the whims of the US president undermines a key benefit of such arrangements: greater stability. Without this stability dividend, potential partners could begin to question whether the costs of forging complex agreements with the US outweigh the benefits, writes Ken Shadlen (LSE International Development).

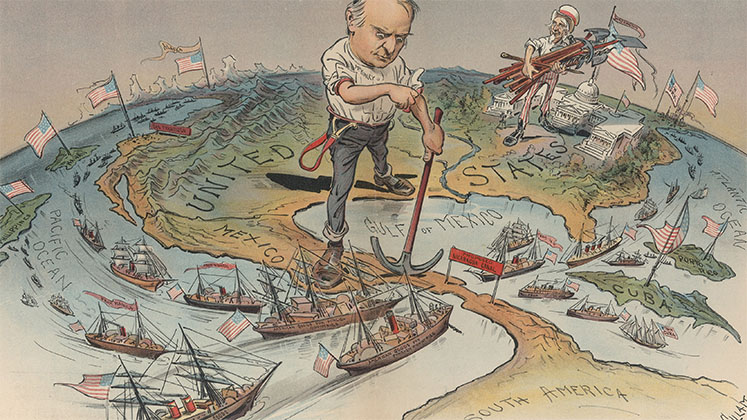

The United States’ last week threatened to apply tariffs on imports from Mexico unless Mexico revamped its approach to Central American migrants passing through the country. This move underscores the power asymmetries in the global economy and undermines the credibility of US trade agreements elsewhere. Essentially, President Trump was threatening to abrogate US commitments under NAFTA (and the World Trade Organization) unless Mexico introduced measures in an area that is not addressed by NAFTA.

These tariffs will not now be applied, and there is debate about just how much Mexico changed its migration policies as a result of Washington’s manoeuvre. Nevertheless, the Trump administration’s linkage between trade and “non-trade” issues such as immigration has profound implications for the political economy of international trade, especially within preferential trade agreements such as NAFTA.

The blurred lines between trade and non-trade issues

Many critics of Trump’s threats claim that immigration policy and trade policy are distinct, and that it makes no sense for the administration to link the two. But this misses the point: what is and is not “trade” is determined politically.

Since the 1980s, the United States has conditioned market access on the introduction and enforcement of a wide range of “trade-related” policies, including investment, intellectual property, government procurement practices, and so on. Market size confers to the importing country the power to define what constitutes “trade,” and the definition of “trade” thus has changed according to Washington’s preferences. In that sense, Trump’s trade-immigration linkage manoeuvre is not at all new.

On the one hand, NAFTA is the outcome of massive linkage of this sort, as Mexico was required to introduce extensive changes to policies and practices in a range of trade-related policy areas in order to qualify for the agreement. On the other hand, NAFTA was meant to protect against further “ad-hoc linkage”, whereby new conditions would be attached at the whim of the United States.

Prior to NAFTA, Mexico’s exports largely entered the U.S. market under the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), which offers preferential market access to exports from developing countries under a wide range of conditions. But GSP preferences can be withdrawn unilaterally, and, being the importing country, the United States changed GSP preferences in response to its changing sentiments. Beneficiary countries always ran the risk of having the US Congress and Executive attach additional conditions to the programme like ornaments on a Christmas tree.

NAFTA and subsequent NAFTA-like trade agreements promised to deliver substantially more predictability and stability than the GSP, but recent events question these premises.

Trump and the NAFTA stability dividend

In 2017-18, Trump warned that Washington would withdraw entirely from NAFTA unless it was renegotiated on terms more to his liking. Last week’s threat to remove preferential market access unless Mexico changed its immigration policies and practices is precisely the sort of behaviour that NAFTA was meant to protect against. The agreement supposedly replaced the unstable preferences of GSP, which were always vulnerable to the whims of US politicians, with preferences that were clearly defined, had fixed conditions, and were less prone to being unilaterally withdrawn. Trump’s behaviour shows that this stability dividend is fragile, and not guaranteed.

Washington’s actions are something akin to the Mexican government announcing it would stop enforcing the copyrights and patents of US firms unless the United States substantially increased science and technology assistance to help upgrade the stock of biologists, chemists, and engineers in Mexico. The reaction to such an announcement would be ridicule, and Washington would claim that NAFTA (as well as the WTO) binds Mexico to protect intellectual property. The United States would assert, moreover, that its science and technology assistance is not covered by NAFTA; Mexico’s threat would elicit no change of behaviour on the part of the US.

Beyond NAFTA per se, these events make one wonder why any country would sign a trade agreement with the United States. After all, if countries already have preferential market access under the GSP, then one of the main benefits of reciprocal trade agreements is to lock-in and stabilise those preferences – even with the need to make substantial concessions on “trade-related” policy areas.

If, in reality, only half of the bargain is locked in and the benefits can evaporate at the whim of the US president, then for many trading partners the benefits of such agreements will be unlikely to compensate for the costs.

Notes:

• Views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or LSE

• This is a slightly modified version of an article that originally appeared on the AULA Blog

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting