Liberalism is often seen as a Western gift to the world that became tragically warped on contact with less developed nations. But where once the region’s intellectuals themselves subscribed to this vision, more recent scholarship shows that Latin American countries charted their own courses towards “liberal” rights and constitutions. Despite even the recent ravages of neoliberalism, the key tenets and institutions of liberalism remain deeply popular, write Catherine Andrews (CIDE, Mexico) and Ariadna Acevedo Rodrigo (Cinvestav, Mexico).

Liberalism is often seen as a Western gift to the world that became tragically warped on contact with less developed nations. But where once the region’s intellectuals themselves subscribed to this vision, more recent scholarship shows that Latin American countries charted their own courses towards “liberal” rights and constitutions. Despite even the recent ravages of neoliberalism, the key tenets and institutions of liberalism remain deeply popular, write Catherine Andrews (CIDE, Mexico) and Ariadna Acevedo Rodrigo (Cinvestav, Mexico).

• Disponible también en español (versión extendida)

In a recent article musing on the state of governance in Latin America, The Economist‘s columnist Bello asks himself whether “liberal ideas suffer in the region because they are imported”. He thinks so, but he nonetheless encourages Latin Americans to persist with them because they will bring “equality of opportunity” and “better public services at an affordable cost”. In a single stroke, Bello resolves all of liberalism’s contradictions and limitations by absolving it of blame for failing in Latin America. It is not liberalism – an “imported” idea – but rather its faulty application, which is in crisis. He conveniently forgets that the 2008 financial crisis left liberalism in crisis everywhere. He also overlooks at least two decades of research relating to the history of liberalism in Latin America.

The West’s gift to the world?

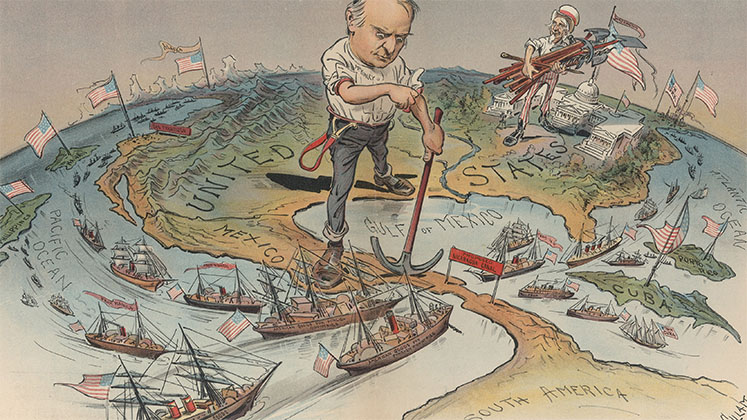

Liberalism, it is often assumed, was the West’s gift to the world. In the retelling of twentieth-century Anglophone scholarship, it was born during the founding of the United States and the French Revolution – two “Atlantic Revolutions” – that destroyed the “old regime” and brought forth the modern political landscape. Liberalism, like its presumed progenitor the Enlightenment and its twin brother Civilization, was the principal ideology that European and US colonisers took with them in their push towards political and economic domination of the world. The good news of liberalism would show the backward nations the road to political and economic salvation.

This historiography defined “the West” as northern Europe and the United States. The roots of the holy trinity could be from outside – Italy, Spain, or the ancient world, say – but its maximum expression and defining aspects could only be found within these limits. All other countries could only ever be considered to have received the good news via the importation of “Western” ideas. “Liberalism” can only be appreciated in its true form in its places of origin: at best, all other liberalisms must bear a national prefix to indicate their variance with the norm; at worst, they should be found wanting as “fakes”.

Liberalism in Latin America

This perspective allowed observers from the nineteenth century onwards to analyse Latin American history in the light of their “reception” of liberal ideas. Once it had been determined that Latin American institutions did not match those in the UK or the US, such observers concluded that any weaknesses must be the result of deficient application or resistance to the good news of liberalism amongst backward elements like the Catholic Church, peasants, or military caudillos.

Within Latin America itself, this narration was attractive to intellectuals of all political stripes. For Conservatives, it provided useful ammunition with which to criticise those they held to be under the sway of the corrupt irreligious foreigner and his “metaphysical” ideas. Liberals were able to denounce any group which opposed them as “backwards” and “despotic”. Liberalism as an unsuccessful foreign import also became a tenet of early twentieth-century Latin American history.

During the hegemony of positivism, lawyers such as Mexico’s Emilio Rabasa would conclude that constitutionalism had failed in Latin America because its institutions had not grown “organically” from its culture. The only solution could be to develop Mexico’s own constitution based on its homegrown liberal spirit – an achievement that the Revolution’s intellectuals would claim for the PRI. This was the “social liberalism” championed by Jesús Reyes Heroles.

Challenging historiographical narratives

Although the legacies of these historiographical narratives have been challenged by historians studying Southern Europe and Latin America since the 1990s, the impact of these studies outside academia has been limited. This historiography argues that liberalism as a political philosophy did not develop exclusively amongst English- or French-speaking thinkers before being “received” and “interpreted” by Hispanic scholars. It makes more sense to talk about a concurrent development of liberalisms in different geographical spaces.

Each Latin American nation debated its own path to a written constitution and did not just adapt the US or any other constitution as is often assumed. Equally, citizenship and its related rights were not imposed as theories taken at random but were fixed locally in response to shared community practices and customs. Hispanic liberalism formed part of “the Age of Revolutions” in much the same way as French or British or US liberalism did. Liberalism can never be spoken of without a prefix because it is not, and never has been, the exclusive property of any nation.

Sadly, liberalism’s ideologues are not paying attention. Bello’s recent column pays ample testimony to this. As he points out, much debate today surrounds the fate of Latin America’s democratic transitions and the “heartless” neoliberal reforms which accompanied them. But why we should see pre- and post-1970s liberalisms as one and the same? Is neoliberalism really a reworking of Latin American liberalism?

Liberalism and neoliberalism in Latin America

Historical research suggests that nineteenth-century liberalism was extremely popular in some areas of Latin America. Military service, wars, and the struggles of local people to obtain and maintain political control of their villages meant that political and civil rights were powerful motivators of popular rebellion. Moreover, liberalism allowed for greater political inclusion (at least for men), including rural populations of diverse ethnic backgrounds and modest means. Economic reforms that we might today consider neoliberal were associated with the conservative dictatorships of the late nineteenth-century.

Today, many who see neoliberalism as heartless in Latin America are far from wanting to give up liberal political institutions such as representative government, human rights, or the separation of powers. Such institutions, with their recognition of “multiculturalism”, have played a key part in the transition process. What they question is the liberal economy. They have seen first-hand that the liberal promise of equal opportunity provided by the championing of public good over private privilege has never materialised. It remains a liberal utopia with no basis in lived experience.

It is surely this utopian thinking that is behind Bello’s conviction that Latin America could neutralise populism via the adoption of “genuine” Western liberalism. What solution does he offer for a United States ruled by Trump today?

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting