Despite opposition from heritage groups, Everton Football Club’s planned move to a new £500-million stadium at Bramley-Moore Dock has this week been given the green light by planning officials. The grade-II listed site is rightly regarded as an important example of Liverpool’s rich maritime heritage, but its name also carries a stark reminder of the city’s historic entanglement with slavery in Brazil, which continued long after abolition in Britain’s own colonies, writes Joe Mulhern (Durham University).

Despite opposition from heritage groups, Everton Football Club’s planned move to a new £500-million stadium at Bramley-Moore Dock has this week been given the green light by planning officials. The grade-II listed site is rightly regarded as an important example of Liverpool’s rich maritime heritage, but its name also carries a stark reminder of the city’s historic entanglement with slavery in Brazil, which continued long after abolition in Britain’s own colonies, writes Joe Mulhern (Durham University).

• Também disponível em português

Given Liverpool’s past status as the epicentre of the British slave trade, much recent historical reckoning has quite justifiably focused on the city’s connections to that traffic until its abolition in 1807 and to slavery in Britain’s Caribbean colonies until 1833. There has also been wide recognition of Liverpool’s links to slavery in the United States and the city’s broad support for the Confederacy during the American Civil War (1861-1865). Less well recognised, however, are Liverpool’s deep connections to Brazil, where the illegal slave trade raged on until 1850 and slavery persisted until 1888. At the very centre of this problematic history was John Bramley-Moore, the Liverpool merchant-cum-politician who gave his name to the dock where Everton plan to build their new home.

When the eponymous dock opened in August 1848, John Bramley-Moore’s political career was just about to take off. A few months later he was installed as Liverpool’s Lord Mayor and by 1854 he had been elected as an MP for the first of two stints at Westminster (1854-1859; 1862-1865). During this period, Bramley-Moore maintained an active interest in the mercantile business that had brought him significant wealth and enough social capital to launch his political career. Bramley-Moore was a “Brazilian merchant”, and it was through this trade that he directly and indirectly profited from the exploitation of enslaved people.

When he arrived in Rio de Janeiro as a young man in around 1820, he was still known as John Moore, only adding Bramley to his surname in 1841. Little is known about his early years in the then capital of the Portuguese empire, but Moore was one of many merchants seeking their fortune in a market only recently opened to British trade. It was in the decade after Brazil’s independence in 1822 that John Moore & Co began to consolidate its position as one of Rio de Janeiro’s principal import-export houses, profiting from an economy and operating in a society where slavery predominated.

In the 1820s alone, slave traders forcibly trafficked over half a million Africans to Brazil to work as slaves on plantations and in a range of rural and urban contexts. Aside from trading in slave-worked exports such as sugar and coffee, Bramley-Moore himself was a slaveowner, making use of forced labour in both his commercial establishment in the centre of the city and on his “extensive and prettily situated” country estate (chácara) at Alto da Boa Vista, a property containing five thousand coffee bushes.

Diary entries penned by John’s brother, Joseph Bramley-Moore, during a visit to Rio in 1831 mention some of these enslaved people. Characteristic of the justifications and delusions employed by British slave-owners and their apologists, Joseph made a point of describing his brother as “a kind and indulgent master”. The idea of the benevolent British slave-owner is of course baseless in a system defined by violence and coercion. Indeed, the diarist would go on to undermine his own argument by recalling the case of Joaquim, a coachman, who had resisted enslavement by escaping and living free in a nearby town before being pursued and ultimately recaptured by John Bramley-Moore.

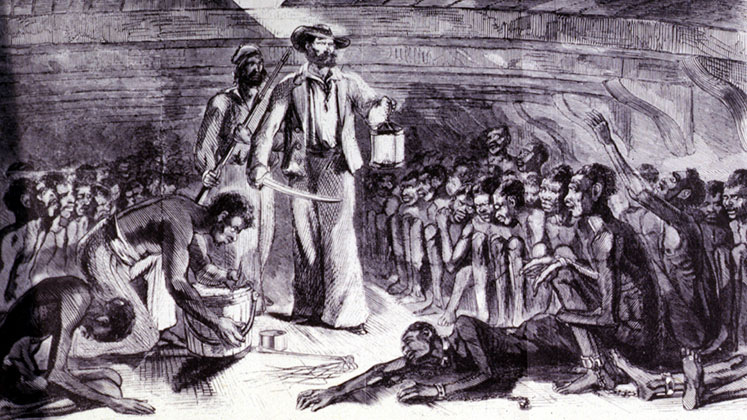

Bramley-Moore was also complicit in the violence of the middle passage through his firm’s role in supplying and financing the slave trade to Brazil. Despite the traffic having been outlawed by the Brazilian government in 1831, an extensive illegal slave trade persisted until the mid-century, accounting for the enslavement of some three quarter of a million Africans. Though organised and carried out by Luso-Brazilian principals, British firms played a central role in the resurgence of the trade through the supply of manufactured goods on lengthy credit terms, which allowed the traffickers to make repayment on the return of their clandestine voyages. These arrangements were so lucrative to British merchants, many with branch houses in Liverpool, that it caused HM Chargé D’Affaires in Rio to admit in 1839 that “very many, nay most of our countrymen in Brazil, are more or less openly, advocates and supporters of the slave trade”.

Though John Bramley-Moore left Brazil in 1835 to manage his business from Liverpool, his firm’s continued connections to the illegal trade are amongst the clearest of any British merchant house in Brazil. In 1839, John Moore & Co, alongside other British firms, declared their public support for Manoel Pinto da Fonseca, by signing an attestation of good character in the Portuguese’s favour. Fonseca had already organised illegal slaving voyages and would go on to become one of the most notorious traficantes of the 1840s.

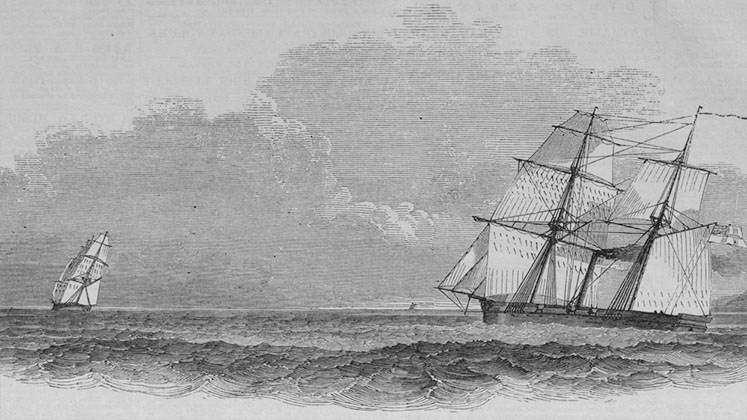

The most flagrant example of Bramley-Moore’s complicity in the illegal slave trade though, was the capture in March 1840 of the Guiana by a Royal Navy cruiser off the coast of West Africa. The Guiana, part owned by Bramley-Moore and another Liverpool merchant, was then taken to Sierra Leone, where it was condemned by the Vice-Admiralty Court for aiding and abetting the slave trade. The Court’s suspicions were well-founded; the vessel had been chartered by well-known traficante Manoel Francisco Lopes while at Bahia, where John Moore & Co had an office, with the intention of supplying the “coast goods” typically employed in the illegal trade.

Despite being one of only a few examples from this period of a British vessel condemned for aiding and abetting the slave trade, the Guiana episode had little impact on Bramley-Moore’s reputation nor his intertwined career in business and politics. The very next year he was elected to Liverpool’s town council as an alderman and would soon embark on the docks project that would ultimately bear his name. Bramley-Moore’s political ascension was sustained by his commercial success, in particular his firm’s increasing interest in the export of coffee, the slave-grown commodity that became the Brazilian economy’s engine of growth from the 1830s onwards. Similarly, Bramley-Moore used his political weight to defend commercial relations with Brazil and its slave economy, both as chairman of the Liverpool Brazilian Association and as an elected MP.

Bramley-Moore died in 1886, two years before the Lei Áurea (Golden Law) finally abolished slavery in Brazil. His wealth, and the political career that it facilitated, was built in large part on the direct and indirect exploitation of enslaved people and their labour. In spite of the very public episode involving the Guiana, Bramley-Moore’s connections to slavery have been sanitised from his legacy. His entry in the Dictionary of National Biography (1901), which has informed many modern references to the man, makes no mention of slavery. This omission also went uncorrected in Bramley-Moore’s revised entry for the 2004 edition of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. As the organisers of the Legacies of British Slave-Ownership project have noted, this is part of a wider process of elision that rendered problematic connections to slavery virtually invisible in British history.

A hard-fought campaign by historians, heritage organisations, and the local community has led Liverpool City Council to commit to installing plaques that contextualise links to slavery on a number of streets named for slave traders. As custodians of a site that will soon find itself in the global spotlight, Everton Football Club and the City Council have an opportunity to do likewise by contextualising an area named for a man so deeply entangled with slavery in Brazil.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

No one could be more shocked by these revelations of John Bramely-Moore,than me his great, great grandaughter . All aspects of slavery are indefensible. I will inform my children and grandchildren of this shameful past. Mercifully I gave up the name Bramely-Moore when I married.

My great uncle, Walter Jones, is listed as a Brazilian Merchant’s Clerk living in Liverpool at the time of the 1911 census. Then in 1914 he was posted to Manaus where spent the rest of his working life, before retiring to Portugal. I know that he travelled with the Booth Line, but do not know which company employed him.

Any information would be greatly appreciated.

Regards,

Owain Evans.

Very Naice

A fascinating article. It is great to learn more about Bradley- Moore. My interest in him has come from the Lincoln election riot of 1862 which followed his election as MP by a small majority. It had been a bitter contest in which he threatened to sue his opponents after they claimed that he had been a slave holder and trader. (I have references in the local press and a history of the local police- if you are interested.) I was therefore particularly pleased to discover your article confirming his direct involvement with slavery.

I have been involved in a project with Wakefield Socialist History Group to investigate some lesser known connections between Britain and Atlantic slavery. This led me to the slave allegations and the Lincoln riot. Might you be able to point me in the direction of your sources for Bramley-Moore’s brother’s’ diary, the capture of the Guiana, and the business in Rio? I did look at your Durham thesis, but must confess, not as carefully as it deserved, but didn’t find any obvious mentions of Bramley-Moore, so I’d be very grateful for any ideas. I hope you get the book published, and please keep me posted , if convenient.

In any case, thanks for producing such a fascinating, and important article.

Robin Stocks

Glad you enjoyed the article, Robin. I think we have been looking at the same material in the local press; the allegations made against Bramley-Moore (by Michael Browne and others) are certainly very interesting and if true would certainly help explain his rise from relative obscurity in the mid-1820s to significant wealth by the time his brother visited Rio in 1831. I was also very interested to see Bramley-Moore’s obfuscated response to these claims, particularly the way he was able to take advantage of local ignorance about the history of the slave trade to Brazil. I hope to include a fuller discussion of this in the book.

The reference for the diary is Joseph William Moore, The Revolution of 1831 with notes by J.M. Harvey (São Paulo:

Sociedade Brasileira de Cultura Inglesa, 1962). The British Library and a handful of universities have copies. I would be happy to point you in the direction of other material (though some is in Portuguese). Please send me an email (my address can be found by searching my surname on Durham’s website).

A very interesting article.

Hopefully when the Grade II listed hydraulic pump house has been restored and opened to the public it will include the true history of the dock as part of its museum these things should never be forgotten important for visitors to be educated on where they are and what happened.

Fascinating article Joe, thank you. I’m a PhD candidate at Faculty of History University of Cambridge. I’m studying my own slave owner ancestors who monopolised the Liverpool, Glasgow Demerara trade known from 1813 as Sandbach Tinne but who traded under different names from 1780 onwards.

I saw a letter of 1847 receiving “a cargo of negros” into Demerara and suspected that they were illegally importing enslaved Africans, perhaps from south of the line in west Africa – which the British didn’t patrol – or perhaps they came from Brazi? That year alone Brazil was reported to have imported 80,000 enslaved Africans.

I’d very much like to discuss this with you. You can inbox me via Instagram or twitter @malikandtheogs

Hasn’t the naming rights been given to USM,who have invested money into the new stadium..?? This will surely negate the historical name of the dock

Very interesting article, I did not know much about the Brazilian slave trade and Liverpool’s connection. It would be useful to include a section on Bramley Moore in the Slavery Museum and for Everton to sponsor the exhibit.

I sense a lot of blue envy here,clearly this development will have a largely positive effect on the local population.After all in the current situation all positives will enhance the future whereas the past cannot alter the effects of this terrible time the world is going through.

Any opposition has always been about the risk to World Heritage Status. Anderson used this to try and get rid of our UNESCO status, so that he could open the floodgates for Peel to build whatever they like at Liverpool Waters. But now that he has gone, hopefully the North Docks are now safe.

The opposition to the developments in the Liverpool Docks, has much more to do the close connection between Peel Holdings the Landlord and our city leaders. Liverpool Waters as Peel Holdings has named the basic Infilling of the historic Dock waters to create development land grabbing in areas built and created by Liverpool citizens and ratepayers. Most of this area had been left seeking Leasehold Developments thus creating a stream of funding via rents for Peel. This area should have been opened up for the construction of housing, that is fit for families not high rise apartments. The Liverpool workers families who actually funded and worked as construction workers, Dock workers and shipping workers, would love to live in a’ Home’ in the area. The new Everton Stadium will offer these families access hopefully to an area of our city currently they are excluded from, at least on match days. Our city leaders have a lot to answer for in respect of the loss of our dockland and indeed the Albert Docks in particular to the outside interests who are profiting from the ratepayers and workers of of great city over hundreds of years.

Bryce, just to address your point on ‘blue envy’, I don’t have a horse in that race, I’m afraid. Though as a visitor to Goodison’s away end to watch Newcastle over the years, I do look forward to the unrestricted views that the new stadium will offer. Of course, for that to happen with any sort of regularity, we’ll have to avoid relegation this season!

An informative article, Joe.

As a history-loving Evertonian, I’ve followed the new stadium project closely but knew nothing of John Bramley-Moore’s life or, for that matter, the UK’s involvement in Brazilian slavery, after it was abolished in Britain.

Where can I find out more on the subject? I particularly like the balanced content in your article, as you explain this difficult subject through one man’s life.

For the record, until I read your blog, I liked the idea of retaining the dock’s name for the new stadium but have clearly now changed my mind.

Thanks Allan, glad you enjoyed the article. In terms of other sources of information, there are a couple of works concerning the use of slave labour by British mining companies in Brazil during this period (e.g. M. Eakin, ‘A British Enterprise in Brazil: The St. John d’el Rey Mining Company and the Morro Velho Gold Mine, 1830–1960’). Outside of this industry, most of the research is ongoing or still unpublished, though I have written another article on this site concerning British bankings entanglement with slavery in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo in the 1860s and 1870s. I’m currently working on a book project that brings these themes together but in the meantime my PhD thesis ‘After 1833: British Entanglement with Brazilian Slavery’ is available to download for free on Durham’s e-thesis repository.

Excellent article – Everton should take a leaf out of Celtic FC’s book and make a stance on this matter. Otherwise, ‘taking the knee’ will just be seen as a hypocritical stance. And by the way, who on earth wrote the 2004 revised entry on Bramley-Moore without making any reference to his involvement in slavery. Past historians have a lot to answer for.

Excellent and educational…..a reckoning of a man who has long since been tarnished by the reality of his life. Even if Romans and people worldwide condoned slavery….once it was established as wrong, lawfully and morally…..he should have stopped. Thanks for a wonderful article…

Their could possibly also be a link with john houlding the owner of the first ground Everton used at Anfield.

He was the landlord a majority share holder of Everton in1878.

He also had links with the west indies and Brazil were he bought raw material for his brewery.(sugar & oil)

His father made his millions from being a cow man selling milk from his cows he grazed off scotland road at the same time John bramley moore was actively importing sugar was used in cow feed.

I must have knew each other because both were councillors, lord mayors ,Conservative polititions and orangemen at the same period of time.

Could the other local mentioned be the houlding family.

Thanks John, these are interesting leads. There is certainly more work to be done on Bramley-Moore’s later career, both in politics and business.

Is their a family legacy today in Liverpool or elsewhere? Who are they? What do they own or fund? There is a plaque to the Irish famine at the dock, the People’s Club should work with the Slave museum/local community will to do something. I say that as an anti-racist and socialist and not as a Liverpool season ticket holder 😜

Thanks Peter. You raise an important point which deserves further investigation. As per newspaper accounts of the content of his will in Dec. 1886, Bramley-Moore appears to have bequeathed much of his wealth (£169,115) to his sons. He also made not insignificant gifts to what is now the RNLI for annual ‘Bramley-Moore Medals’ (£1000) and to an institution for the poor in Gerrard’s Cross, Buckinghamshire, for ‘Mrs Bramley-Moore’s Coal Gift’ (£500). His will being listed as ‘resworn probate’ in 1887 casts some doubt as to whether these bequests were realised, so further research will be needed.

Maybe rename the stadium …Quilombo????

Excellent piece Dr Mulhern-this is a reminder reminder of the past and a time for reflection for all of the kind of the world we want to live in and our children to be taught of our past in school about our history and heritage.

There was also a pub on the Dock Road called the Bramley Moore. I have just written a history of my street in Liverpool and I was heartened to find that there was a herring importer in my street who fought on the anti slavery side in the Civil war . Very brave I am sure

The Bramley Moore pub is still there Helen. It was open up until the latest lockdown.

Heritage groups were not agains the development itself, but the risk of losing World Heritage Status from UNESCO. If that has been averted, this stadium is nowhere near as bad as all the skyscrapers that Peel want to put on the site between here and the Pier Head.

If I remember correctly Bramley-Moore also received the Order of the Rose from Pedro II for speaking out against The Aberdeen Act in Parliament.

Thanks Laurence. Bramley-Moore received the Order of the Rose for defending Brazil’s position in Parliament during the Christie Affair in 1863. Though ostensibly a diplomatic disagreement about shipping, the underlying cause was William D. Christie’s (British Minister in Brazil) frustrations concerning the Brazilian government’s failure to ensure the freedom of Africans liberated under the Anglo-Brazilian anti-slave trade treaty (1826) and its intransigence on the wider question of Africans illegally imported after Brazil’s domestic anti-slave trade law of 1831. Brazil’s position included its own frustration at Britain’s repeated refusal to repeal the Aberdeen Act of 1845, hence Bramley-Moore’s reference to this ‘grievance’ during speeches at Westminster.