Long after the abolition of slavery in the British colonies, a predecessor bank of today’s Lloyds Banking Group knowingly held enslaved Afro-Brazilians as security against its loans, sometimes even forcing their sale to settle debts. Contrary to popular belief, the case of London and Brazilian Bank shows that Britain’s involvement in slavery did not end in 1833; it simply took on different forms in different places, writes Joe Mulhern (Durham University).

Long after the abolition of slavery in the British colonies, a predecessor bank of today’s Lloyds Banking Group knowingly held enslaved Afro-Brazilians as security against its loans, sometimes even forcing their sale to settle debts. Contrary to popular belief, the case of London and Brazilian Bank shows that Britain’s involvement in slavery did not end in 1833; it simply took on different forms in different places, writes Joe Mulhern (Durham University).

• Também disponível em português

Recent Black Lives Matter protests have prompted renewed scrutiny of numerous British companies’ historical ties to slavery. Banking institutions, including major high street names, have been a particular focus of articles based on the exhaustive research of UCL’s Legacies of British Slave-Ownership project (UCL-LBS).

Using this project’s database, journalists have been able to reveal that individuals involved in predecessor banks of the likes of RBS, Barclays, and HSBC were amongst the many slave-owners who received a share of the £20 million compensation (roughly £17 billion in today’s money) that was paid out by the British government following the abolition of slavery in the British colonies in 1833.

Given the focus of the UCL-LBS project, it is understandable that much of the recent controversy has revolved around links to slavery in Britain’s former colonies. But this vital historical reckoning must also take into account British banking’s connections with foreign slaveries, which persisted far beyond 1833.

Lloyds, the London and Brazilian Bank, and slavery in Brazil

In the case of Brazil, a predecessor bank of today’s Lloyds Banking Group remained deeply entangled with slavery until the eve of abolition in 1888. That is, more than 50 years after the abolition of slavery in the British colonies, the London and Brazilian Bank continued to exploit the labour and market value of enslaved people to devastating effect, all the while concealing this complicity from investors and the public in Britain.

Established in 1862, the London and Brazilian Bank operated independently until 1923, when Lloyds Bank acquired a controlling stake in the business. Lloyds Banking Group’s website does acknowledge this shared history and has recently been updated to recognise the slaveholding past of the London and Brazilian Bank’s first chairman John White Cater. “[A]n old coffee planter”, Cater received slave compensation for claims in Jamaica, as did fellow board member John Bloxham Elin. A third board member, Edward Johnston had owned slaves in Brazil and married into a coffee plantation-owning family in Rio de Janeiro. Wealth accrued from slavery in both the Caribbean and Brazil helped to establish a bank that would go on to invest in the continued exploitation of enslaved people. [Ed: Lloyds Banking Group have updated their website in response to this article.]

The coffee connection of the bank’s founders would continue throughout its early operations, with this slave-grown commodity being the key engine of growth in the Brazilian economy at the time. In spite of its intended commercial remit, by 1868 the bank had amassed a mortgage portfolio secured by several São Paulo coffee plantations and the 800 or more enslaved people working on them. This human collateral had been transferred to the bank to secure a substantial line of credit of £150,000 (roughly £9 million today) from the private banking house Gavião Ribeiro Gavião, a major financier of São Paulo’s burgeoning plantation economy and a key player in the interprovincial slave trade.

Sanitising Brazilian slavery in London

The bank’s London headquarters would later chastise the branch managers who sanctioned the initial transaction. But their criticism did not stem from the moral abhorrence of financing slavery or holding people as collateral, but rather from the fact that recovery of these debts was notoriously problematic. On occasion the bank resorted to judicial proceedings, processes that could have devastating impacts on the lives of the enslaved.

This was the case during the bank’s pursuit of a debt owed by a Rio de Janeiro coffee baron in 1869. When the Baron do Turvo defaulted on his loan, the bank’s lawyers pursued a court-enforced auction of 103 enslaved plantation labourers, amongst whom were families with children as young as a year old. Eventually, at least 30 individuals were sold at public auction, their lives changed forever by a British bank’s attempt to balance the books.

The London and Brazilian Bank’s entanglement with slavery was obfuscated by sanitised language at shareholder meetings. There was a legal imperative for this as an 1843 law had prohibited the enforced sale of slaves to settle debts owed to British creditors in foreign jurisdictions. However, the bank was also wary of provoking unrest amongst investors in Britain, where anti-slavery sentiment had become a tenet of national identity. For these reasons, references were repeatedly made to “estates”, “lock-ups”, and “other property”, but never to those enslaved people held as collateral.

Involvement both direct and indirect

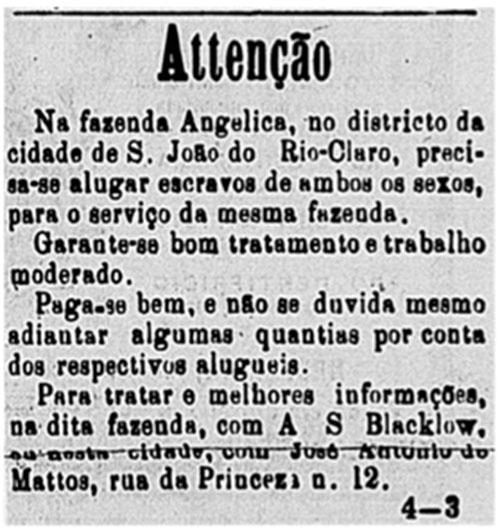

Investor relations also influenced the way the bank managed its own extensive Angélica coffee plantation in São Paulo’s interior between 1871 and 1881. After initially proclaiming a commitment to free labour, the failure of an experiment with German immigrants prompted managers to employ gangs of enslaved workers from around 1876 onwards. Again, this direct involvement with slavery was obfuscated in shareholder meetings, with the chairman disingenuously stating in 1880 that “[as] an English company the Bank could not employ slaves”. In reality, the bank had taken advantage of a loophole in the 1843 Act which allowed the hiring of slave labour in foreign countries.

When the long-awaited sale of the Angélica plantation was completed in 1881, the chairman performed an about-turn, declaring that “the bank now had not a single slave in its employment”. However, even after the sale of the property, the bank remained entangled with slavery because the buyer’s purchase-money mortgage was secured by 80 slaves that would work the property.

Six years later, during a period of heightened slave resistance that preceded abolition, the plantation’s new owner, the Baron de Grão-Mogol, would claim that he was unable to free his remaining workforce due to their continued status as human collateral. It was only the process of abolition in Brazil that would remove the stain of slavery from the London and Brazilian Bank’s operations.

Though this bank is one of the few with a clear link to a modern institution, a great many British enterprises and individuals continued to exploit slavery long after British abolition. The existence of these British slaveholders in places such as Brazil, Cuba, and the southern United States long after 1833 challenges narratives that place abolition at the centre of Britain’s relationship with slavery, effectively whitewashing a centuries-long history of exploitation.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Banner image: A coffee plantation in Brasil, c. 1885, Marc Ferrez, public domain

• This article draws on the author’s doctoral dissertation After 1833: British Entanglement with Brazilian Slavery (University of Durham, 2018)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Researching my family tree I have discovered one of my ancestors ,Edward A benn was a director and Manager of the Brazilian and London Bank.

I note with dismay the bank was involved with the slave trade.

would you please be so kind and forward any relevant information.

If you can tell me anything about the Musson family in brazil it would be much appreciated.

Regards Michael Benn