The discourse of crisis promoted in the first two years of the Moreno government (2017-18) was a political strategy designed to create distance from the administration of his predecessor Rafael Correa. But its overemphasis on the fiscal deficit was inconsistent with the reality of the macroeconomic situation, and the economic policy stemming from it sidelined important concerns over productive capacity in favour of providing benefits to new allies in the private sector, write Katiuska King (Central University of Ecuador) and Pablo Samaniego (Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador).

The discourse of crisis promoted in the first two years of the Moreno government (2017-18) was a political strategy designed to create distance from the administration of his predecessor Rafael Correa. But its overemphasis on the fiscal deficit was inconsistent with the reality of the macroeconomic situation, and the economic policy stemming from it sidelined important concerns over productive capacity in favour of providing benefits to new allies in the private sector, write Katiuska King (Central University of Ecuador) and Pablo Samaniego (Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador).

Although Ecuador’s current president Lenin Moreno was elected under the auspices of his predecessor Rafael Correa’s political movement (PAIS Alliance), once in office he distanced himself from Correa by allying with business sectors and the political right while promoting a discourse of “exposing” failures of the previous model. As we discuss in our recent article for Ecuador Debate, this affected public perceptions of the economy in ways that justified a shift towards austerity, but the reality of economic policymaking also created many winners amongst his new allies.

Narrating economic crisis in Ecuador

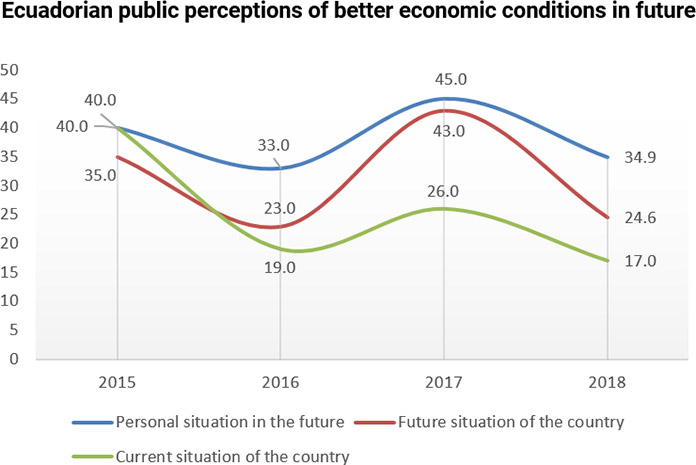

When Moreno took office in May 2017, public perceptions about the state of the economy were actually very positive (see chart below), reaching levels similar to their recent peak in 2011, during the second term of Rafael Correa. But expectations began due to change due to attempts to discredit the previous government’s economic strategy rather than as a result of attempts to implement any new policy platform.

To this end the word “crisis” began to be used consistently, with Moreno linking it exclusively to the issue of the public sector deficit. And with the active help of the media and Correa’s political opponents, this sense of “crisis” became part of the public’s collective unconscious, irrespective of its accuracy.

Although this in itself was a serious issue, an even greater problem was the resulting change in economic expectations, whose negative turn militated against the possibility of demand-side policies overcoming the economic slowdown. Instead, the consensus “crisis” position in the official discourse acted in part as a self-fulfilling prophecy, helping to bring about a significant reduction in growth in 2018. As growth fell between 2017 and 2018, there was also a notable reduction in the percentage of the population that believed that the government was acting in the interests of the people, which dropped by 21 percentage points from 38 per cent to 17 per cent.

Whose crisis? Whose solutions?

The political strategy of narrating the results of the previous administration as a crisis even fed into official projections on the state of the economy: a few months into the Moreno government, the growth estimate for that year was lowered to 0.7 per cent from an initial projection of 1.4 per cent, yet in the end the economy grew by 2.4 per cent (according to the Central Bank of Ecuador).

A political economic discourse focused on attacking fiscal deficits also reinforced the message that the public sector was responsible for all evils, which simultaneously enabled promotion of austerity, concessions, privatisations, and monetisation of public assets, even if this meant weakening the provision of public services.

This is not to deny that there was a fiscal problem. Fiscal deficits have indeed increased in recent years, but in 2017 the fiscal deficit to GDP indicator fell from 7.3 per cent to 4.5 per cent. Between 2007 and 2017 external debt increased from 13.7 per cent to 30.4 per cent of GDP. In that context, in 2017 tax expenditures increased to 1,639 million dollars for income tax alone.

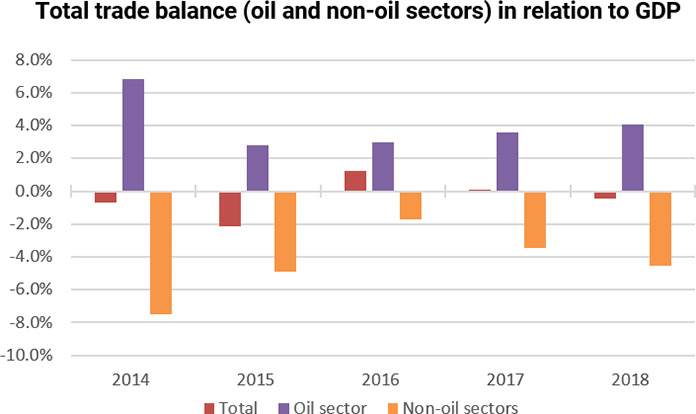

The other serious problem faced by the Ecuadorian economy is external, as Ecuador maintains a dollarised economy, and the only source of money creation is the balance of trade. Despite the negative balance of the non-oil sector (see chart below), any strategic vision for production was discarded. Rather, the national planning system was dismantled and productive policy was replaced by a search for free trade agreements, yet these failed to materialise. The only agreement currently in place is with the European Union, and this deal was signed by Moreno’s predecessor.

‘Productive Development’, dollarisation, and economic contradictions

Focusing on fiscal policy over the rest of the macroeconomic context in order to achieve a differentiation from the previous administration has also obscured numerous contradictions in economic management.

“Productive Development” legislation, for example, increased incentives to the private sector and offered a tax amnesty at the same time that the government talked tough on the need to increase tax revenues. A new clause also allows the previous legal limit on external indebtedness to be circumvented, even though the Moreno government’s earliest and most trenchant criticism of the Correa administration was its supposedly irresponsible level of external indebtedness (around 43% of GDP). Credit agreements backed by oil pre-sales or by minerals were also maintained after renegotiation.

One of the main winners under Moreno has been the banking sector. As a symbolic act, in 2017 the government gave banks control over operation of the vital electronic-wallet system used to ease the liquidity problems of Ecuador’s dollarised economy, even though recently approved prices for small payments can be up to four times higher than when the system was operated by the Central Bank. Banks in turn increased the supply of credit in the economy, both as a political gesture and to take advantage of the looser regulatory environment put in place by Moreno.

Overall, both the discourse and the implemented economic policy were inconsistent with the reality of the macroeconomic situation. And ultimately, in early 2019, the search for solutions was delegated to the International Monetary Fund, whose approach is again to focus on the fiscal deficit rather than the country’s productive capacity.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• This post is based on the authors’ own article “A río revuelto, ganancia de varios pescadores” (Ecuador Debate, 2019)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting