Latin American countries have increased the state’s role in pension provision since the mid-2000s. Bolivia has introduced changes in which the state has a bigger role, and this is linked to the reforms promoted by the socialist MAS party. Still, the private system has endured, Leandro N. Carrera (LSE Public Policy Group) and Marina Angelaki (Panteion University) explain.

Since the 1980s, the region has been at the forefront of pension privatisation. But in recent years, many Latin American countries have introduced reforms of the opposite direction by increasing the role of the state in pension provision. A look at the recent experiences of re-reforms shows that while some countries have eliminated the mandatory pillar of private accounts, others have maintained it and have introduced significant changes. In a recently published article, we explored how policy legacies from previous reforms and political institutions have reshaped the outcome in Southern Cone countries.

The Bolivian pension system has not escaped this process of continuous transformation. It was first reformed in 1997 with the introduction of a pillar of private accounts and continued with a series of reforms since the mid-2000s that increased the state’s role, albeit always maintaining the system of private accounts. The impact of COVID-19 has sparked discussions about allowing partial withdrawals from private pensions to alleviate members’ hardship situation throughout the region, and the government has recently legislated to allow such withdrawals. We contend that policy legacies and institutions are key to understanding recent changes and that a closer look at the Bolivian case may help us understand policy changes in other Latin American countries.

A brief history of the Bolivian pension system

The privatisation of the Bolivian pension system in 1997 eliminated the state-run PAYG public pillar, and all workers were forced to join the new system of private accounts. Two private pension administrators dominated the new system (Administradoras de Fondos de Pensiones, AFPs). Given its mandatory feature, it managed to accumulate a moderate level of savings, over 22 per cent of GDP by 2010. Yet, low coverage and low density of contributions (the latter leading to low future payments) resulted in low support for the private system. The government also introduced Bonosol, a non-contributory pillar for those aged 65 and over who met specific eligibility criteria.

In 2006, the left-leaning, movement-led administration of Evo Morales focused on introducing significant labour and social policy changes. While his party MAS (Movimiento al Socialismo) had a majority in the Chamber of Deputies, it had a minority in the Senate. Morales had to negotiate cabinet positions with some organisations that did not support him initially to strengthen his administration. Therefore, some groups would not hesitate to mobilize when considering that their specific demands were not heard.

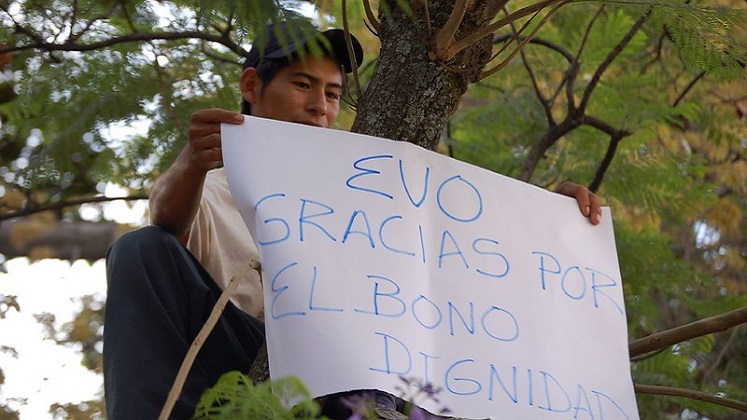

During his first presidential term, Morales proposed a reform of the non-contributory Bonosol. Its low amount (around $25 per month) meant that the grassroots movements supported the higher amount of the proposed non-contributory Renta Dignidad (at around $40USD). By contrast, the Bolivian Workers´Confederation (COB) opposed the reform, arguing that the focus should be on the reform of the private pillar. In Congress, the Senate initially rejected the bill out of concerns by centre-right parties on the fiscal impact of the reform. However, after the Chamber of Deputies insisted on the original version of the bill, mass demonstrations by grassroots movements took place in support of the bill. When the Senate was to vote on the bill, protesters prevented opposition senators from entering the building, and MAS senators ended up approving it.

Even after introducing the Renta Dignidad, the government’s key concern remained the private system and it continued working on reforming it. The passing of Renta Dignidad showed that Congress support was key where the presidential authority was not concentrated. Following the approval of a new constitution in 2009 that expanded the power of the president, the government started working on a new reform focusing on improving benefit adequacy. It increased Renta Dignidad and introduced a new first-pillar contributory pension (Pensión Solidaria). Most notably, the bill included eliminating the private pension administrators (AFPs), replacing them with a government-run pension administrator (Gestora Pública) yet to be established. This time, and even though the government did not struggle to gain Congress support, it made significant concessions to the grassroots organisations to secure their vital support for the reform, reducing the retirement age to 58 years.

That government’s large majority helped in passing the bill swiftly. Critically, the individual private pension accounts were maintained but managed by a state-run administrator (Gestora Pública de la Seguridad Social) set up later.

Still, private pension administrators showed concerns. While the government initially offered to buy the AFPs’ assets to be transferred to the new Gestora, it later withdrew the offer over concerns that the new public administrator would inherit judicial claims for unpaid contributions had to be recovered. Given the bargaining weight of the AFPs, (with assets around 20 per cent of GDP), they agreed with the government a “transition” to transfer the administration of the individual accounts to the new Gestora. In exchange for recovering unpaid contributions and sharing members’ data with the new state-run administrator, the government agreed to compensate the owners of the two AFPs.

Recent changes and the future of the Bolivian pension system

The transition to the new Gestora is still ongoing. The government has postponed the start of operations of the Gestora Pública de la Seguridad Social several times. It was delayed for ten years and started in 2021 but is not yet managing the private pension accounts.

Since last year, some policymakers and grassroots organisations have proposed partial withdrawals from private pension accounts to allow people to have some extra funding amid the Covid-19 crisis. Discussions heated up in early 2020 where, once more, grassroots movements mobilised against the private pension system pushing for reform to allow full withdrawals. The new administration of Luis Arce won a large majority in Congress, and he put in place a task force to draft a bill allowing the partial of up to 15% of accumulated savings, subject to some conditions.

The strong support in Congress has been key to ensuring the government lead this debate, rather than grassroots or opposition parties. Officials highlighted that the reform goal was not to undermine the private system and that people should carefully consider whether a withdrawal is in their best interest. Thanks to its solid majority in both chambers, the MAS passed the bill in August. Once again, the legacy from previous reforms and a robust institutional setting and solid congress support helped in this outcome, which still features a system of private pension accounts.

Peru and Chile have also recently passed pension withdrawals, but the difference is that the opposition has been promoting those changes to undermine the private accounts system. The particular legacies of weak coverage and low expected pensions, coupled with weak governments and a stronger industry help understand why its opponents have proposed these withdrawals that may significantly undermine the system.

In a region where the adequacy of pensions is still well below minimum standards, pension policy will remain high on the agenda. That is why it is essential to analyse policy legacies and political institutions to understand how and when policy changes occur.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

• Banner image: Seyhan Ahen / Shutterstock