With the Colombian peace process under pressure from increasing levels of violence, Anika Oettler (Philipps-Universität Marburg) looks at how the country’s innovative transitional justice system has adapted to focusing on the present as well as the past.

With the Colombian peace process under pressure from increasing levels of violence, Anika Oettler (Philipps-Universität Marburg) looks at how the country’s innovative transitional justice system has adapted to focusing on the present as well as the past.

For well over half a century, Colombia has endured a conflict so violent that it has cost the lives of an estimated 200,000 people, with another nine million becoming victims of displacement, disappearances, torture, sexual violence, kidnappings, and forced recruitment.

The 2016 peace accord between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) represented an important effort to break out of this cycle of violence, and Colombia now boasts the most comprehensive and holistic approach to transitional justice that the world has ever seen. Yet the continuation of violence alongside efforts at peacebuilding has taken Colombia’s new system on a remarkable journey towards reinventing institutionalised reconciliation practice.

Transitional justice before and since the peace agreement

Colombia’s Comprehensive System of Truth, Justice, Reparation, and Non-Repetition (SIVJRNR, hereafter Comprehensive System) consists of the Missing Persons Search Unit (UBPD, hereafter Search Unit), the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP, hereafter Special Jurisdiction), and the Commission for the Clarification of the Truth, Coexistence, and Non-Recurrence (CEV, hereafter Clarification Commission). These institutions are part of a holistic peacebuilding framework that aims to address the root causes of violent conflict, particularly through rural reforms, drug policy, and guarantees of political participation.

But even prior to the creation of the Comprehensive System, Colombia demonstrated a trend towards establishing mechanisms of transitional justice in the midst of violent conflict. Indeed, it was the right-wing Uribe government that began to build this architecture in the 2000s.

In 2005, Law 975 established the basis for the demobilisation of thousands of paramilitaries. The Victims Law, passed in 2011 under president Santos, also led to the establishment of a reparations programme, land restitution efforts, and the creation of the National Centre for Historical Memory. These institutions endure, today providing additional weight and structure to the wider Comprehensive System.

The changing functions of transitional justice institutions

The activities of the Special Jurisdiction, Search Unit, and the Clarification Commission have only recently begun, but evidence to date suggests that important shifts are taking place. The three institutions have evolved to become social worlds – or subworlds of the Comprehensive System – whose “universes of discourse” are constituted by communication and activity around a primary activity and its related offshoots. But the specific conditions of chronic violence in Colombia have also brought important changes, the most notable of which has been a shift away from the classic primary activities of transitional justice institutions.

The Special Jurisdiction, for example, has moved away from punitive justice towards restorative justice, which focuses more on responsibility and restitution for wrongs committed. This also implies taking on the key task of public recognition that is often performed by truth commissions.

The primary activity of the Search Unit is to locate the disappeared, but there is also a related cluster of activity focusing on accompanying and supporting their relatives. Many of the Unit’s everyday activities, conventions, sites, and technologies resemble those pioneered by truth commissions.

As Diana Gómez noted in these pages, from the outset it was clear that the Clarification Commission also needed to “rethink the role of truth commissions”, and this was reflected in its mandate to elaborate a “broad explanation of the complexity of the conflict”, to “promote and contribute to recognition [of victims]”, and to “foster conviviality in the territories”.

Overall, the Colombian system of transitional justice has developed through constant introspection and readjustment of its activities, which has seen it enter into new arenas and activities; traditional functions have become blurred.

Transitional justice in the midst of violence

More importantly still, the death toll from politically motivated violence is rising again in Colombia. INDEPAZ reports that 666 social leaders were killed between December 2016 and September 8, 2019. And according to FARC, 169 demobilised guerrillas have been assassinated since the peace accord. These scandalous numbers highlight not only the absence of institutional capacity for law enforcement but also the prevailing lack of the political will to prevent the phenomenon from continuing.

Though they have long suffered from cyclical political violence, there was a particularly violent start to 2020 for four communities in Bojayá, Chocó, which were seized by 300 members of the paramilitary group Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia. This is typical of established patterns in the targeting of civilians, and it testifies once again to the sloth and inadequacy of governmental responses.

Crucially, these abuses would be prevented by implementation of chapter two of the peace accord, which is devoted to citizen participation and guarantees for political and social movements. Notably, it was the Clarification Commission that released a statement on 6 January 2020 calling for decisive action to remedy the situation, which effectively started to create a space for public dialogue on addressing the tragic implementation gap undermining chapter two.

More broadly, the Commission also speaks out against the wave of assassinations and threats targeting social leaders, human rights defenders, and demobilised guerrilla fighters, which represents a marked shift away from its truth-finding function and towards public recognition of human rights violations both past and present.

The Commission was formally established in late November 2018, but it had had little time to organise this momentous step. The commissioners had to prepare budgets, secure funding, hire staff, solve logistical problems, develop organisational structures, and design the processes by which they would work. They also initiated collaboration with victims’ organisations, civil society, academic partners, and the international community. Most importantly, it was the commission that decided on the parameters of truth-finding and the activities that it would carry out to that end.

Achievements of Colombia’s Comprehensive System

Taking a look at the early achievements of the Commission, again the paradigm shift in transitional justice shines through. The Commission does follow some classical patterns of truth-seeking, opening 19 so-called truth houses in areas of severe armed conflict to collect testimonies and elaborates a truth report.

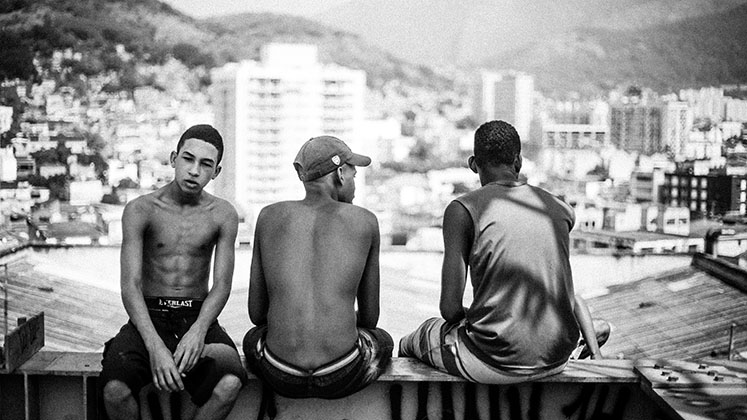

The second Non-Repetition Dialogue took place in Arauca on 12 September 2019

But, less typically, public encounters have also become one of its primary activities, with its series of “Encounters for Truth” focusing on systematic gender-based violence and disappearances. Most strikingly of all, the Commission arranged five public Non-Repetition Dialogues to tackle persistent violence against social leaders, publicising them under the hashtag #TheTruthIsWithTheLeaders. These events in Bogotá, Arauca (see video above), Córdoba, Barrancabermeja, and Quibdó represent a fundamental change in the primary activity of the Clarification Commission.

As Timothy Garton Ash wrote in 1998, truth commissions provide public “history lessons”, but these Non-Repetition Dialogues add new symbolism via their unusual materiality. The sets used for these events are overwhelmingly white, a colour usually evoking purity, clarity, innocence, and safety, as well as coolness and sterility. The format more broadly resembles something between a TV show and the semicircular theatres of a Greek polis. Participants themselves do not sit together at a table, though this is often seen as an “in-between” space that relates and separates at the same time. Instead, there is a white void front and centre, with participants, hosts, and witnesses arranged left, back, and to the right.

It remains to be seen if this dialogue can produce narratives and explanations to fill this void or if instead the process itself will collapse into it, but it is already remarkable that the primary activity of the Commission has shifted so far towards reconciliation and dialogue.

The objective of transitional justice has always been to prevent human rights violations from being committed again. In Colombia, however, it has faced the special challenge of violences and abuses that are both past and present. Though the wider peace process has faltered, the gradual differentiation and integration of transitional justice in a context of ongoing violence has led to productive shifts and innovations in the core activities of transitional justice institutions.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting