One crucial unintended consequence of the Colombian peace process has been a surge in the targeted killing of local community leaders, with over 500 assassinated since 2011. Leaders tend to be killed by armed groups excluded from the peace process that aim to thwart civilian mobilisation in order to consolidate control over formerly FARC-held areas. Those areas with higher judicial inefficiency and where dispossessed farmers have begun to reclaim their land suffer the most. This shows how incomplete peace agreements can inadvertently increase insecurity by triggering violent territorial contestation, write Mounu Prem, Andrés Rivera, Dario Romero, and Juan Vargas.

• Disponible también en español

Peace agreements are usually imperfect and far from comprehensive. They need to address the specificities of particular conflicts and are shaped by political constraints both internal and external. The numerous challenges of peacemaking are likely to be exacerbated when peace deals are made with only some of the armed groups involved in a multi-actor internal conflict.

Colombia is a case in point. The recent peace process between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) – begun secretly in 2011 and concluded in 2016 – excluded other groups such as the National Liberation Army (ELN), criminal groups emerging out of paramilitary forces, and FARC dissidents opposed to a peace agreement.

We study the unintended negative consequences generated by this partial peace process in a recent paper, focusing specifically on the systematic killing of local social leaders which has taken place over the last few years.

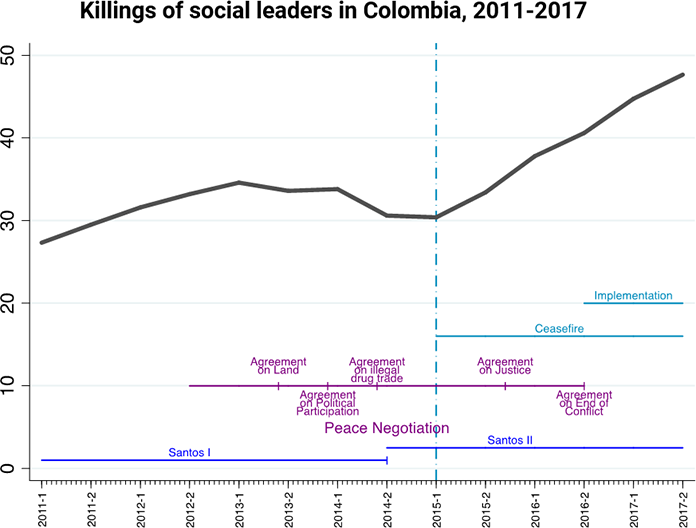

From January 2011 to December 2017 almost 500 social leaders were killed in Colombia. There appears to have been a significant increase in killings since the beginning of 2015 (see below), also the point at which the FARC implemented a permanent ceasefire within the framework of the peace process (indicated by the vertical dotted line).

As government forces largely failed to occupy and build institutional capacity in FARC’s former strongholds, we argue that the ceasefire created a vacuum of power in these valuable territories that other armed groups rushed to fill.

Targeting social leaders constitutes a grimly effective strategy for this kind of territorial contestation in civil wars. By killing local social leaders, other armed groups reduce collective action from communities and thereby increase their own ability to exercise control locally.

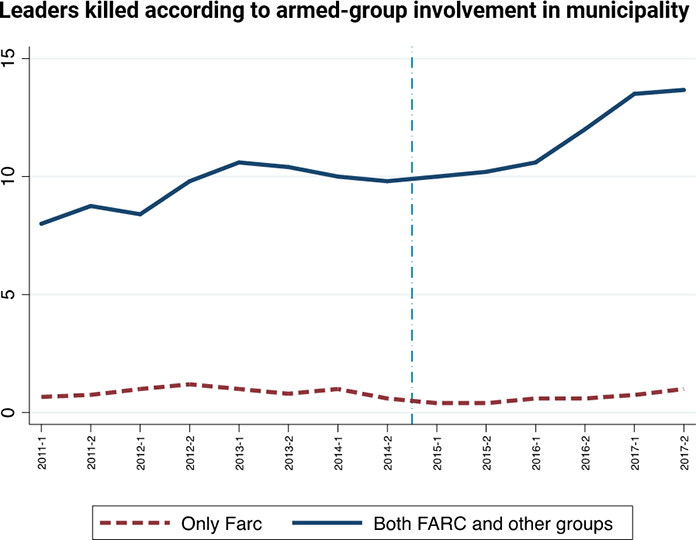

Specifically, we show that after the start of FARC’s permanent ceasefire the killing of social leaders increased disproportionately in previously FARC-dominated zones in the proximity of areas where other armed groups were present.

As the graph below shows, when the permanent ceasefire is announced (vertical line), the number of social leaders killed remains almost constant in municipalities that have prior FARC presence but are not exposed to the influence of other armed groups. In contrast, the number of killings increases dramatically in areas both controlled by FARC and exposed to the influence of other armed groups.

Consistent with our interpretation, we find that the killing of social leaders is not explained by a differential change in the overall homicide rate. Thus, the post-ceasefire rise is explained neither as part of a jump in indiscriminate killings of civilians or a differential change in reporting rates for previously FARC-controlled areas. Beyond this, we also show that the killing of leaders is exacerbated in areas with high demand for land restitution and weaker state capacity in the form of an inefficient local judiciary.

Overall, the killing of social leaders, we argue, constitutes an unintended negative consequence of a partial pacification process that was not accompanied by an effort to consolidate state control in former FARC strongholds.

Though the historic agreement between the government and the FARC in 2016 represented a tremendous opportunity to achieve a lasting peace, we fear that this increase in killings of social leaders may mark the beginning of a new and more sophisticated stage of social disruption in Colombia. We can only hope that time will prove us wrong.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Draws on the authors’ “Killing Social Leaders for Territorial Control: The Unintended Consequences of Peace” (2018)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting