At the end of March, the US Justice Department charged Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro and other government officials with “narcoterrorism”. Along with sanctions and naval counternarcotics operations near Venezuela, the charges are part of the Trump administration’s campaign to oust Maduro. Even if this strategy ultimately proves successful, it will do little to help re-establish democracy in the long term, writes John Polga-Hecimovich (US Naval Academy).

At the end of March, the US Justice Department charged Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro and other government officials with “narcoterrorism”. Along with sanctions and naval counternarcotics operations near Venezuela, the charges are part of the Trump administration’s campaign to oust Maduro. Even if this strategy ultimately proves successful, it will do little to help re-establish democracy in the long term, writes John Polga-Hecimovich (US Naval Academy).

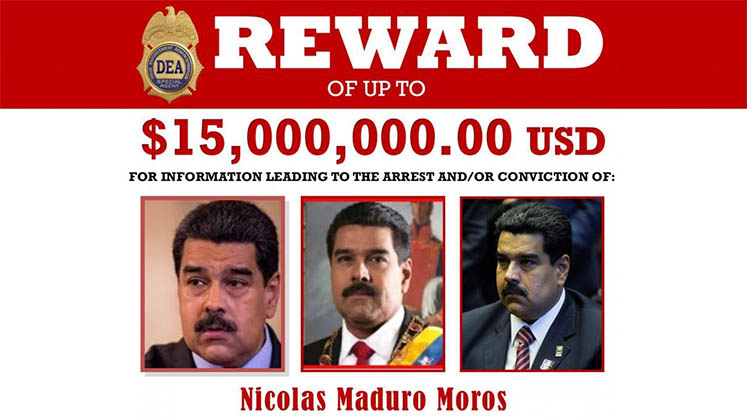

The United States appears bound to a maximum pressure strategy to force Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro from power. On top of layers of economic sanctions, on 26 March US Attorney General William Barr issued charges of “narco-terrorism”, drug trafficking, and corruption against Maduro, Defence Minister General Vladimir Padrino López, and a dozen other government officials, offering a $15 million reward for information leading to Maduro’s capture and conviction. Save for Manuel Noriega in 1988, the indictment of a ruling head of state is unprecedented and underscores the campaign of coercive diplomacy the US is pursuing to unseat the Venezuelan dictator.

The US has added other measures: it deployed Navy forces near Venezuela in April, ostensibly for drug interdiction, and then issued a license to energy company Chevron to stay in Venezuela until 1 December 2020, but essentially barred the company from producing oil in the meantime. Meanwhile, Maduro is scrambling to face the challenges posed by the collapse of international crude prices as well as the dangers of the COVID‑19 pandemic. Once again, Maduro appears to be in a vulnerable position.

How did we get here?

Since Maduro took office in April 2013 after the death of his mentor Hugo Chávez, Venezuela has descended from a hybrid regime – combining democratic and authoritarian traits – into an outright dictatorship. Maduro postponed a recall referendum against him in late 2016 and was re-elected in a fraudulent election in May 2018, closing off institutional channels of political change. During this time, the country’s economy contracted and hyperinflation left a majority of the population mired in poverty, both factors contributing to the more than 4.5 million people who have emigrated.

On the basis of the flawed presidential election, the political opposition used a constitutional article to declare the office of the president vacant, and voted in Juan Guaidó, then president of the National Assembly of Venezuela, as interim president in January 2019. Many democratic governments around the world subsequently recognised Guaidó, while Maduro retains the backing of the armed forces and the leaders of Russia and China, amongst others. The Donald Trump administration, meanwhile, has promised to unseat Maduro, pursuing an escalating series of economic sanctions against individuals and the state-owned oil company Petróleos de Venezuela (PdVSA) in 2018 and 2019.

Narcoterrorism

The March indictment of Maduro and other senior officials on charges of narcotrafficking and support for terrorism against the US ratchets up the pressure on the Venezuelan government. Amongst other accusations, the Department of Justice contends that Maduro is a leader of the so-called “Cartel de los Soles” (Cartel of the Suns) drug trafficking organisation and has used Venezuelan state infrastructure to conspire with the demobilised FARC guerrilla group in Colombia in order “to flood the United States with cocaine in order to undermine the health and wellbeing of our nation.” The four different charges carry a mandatory minimum sentence of 50 years’ imprisonment.

As I have written elsewhere, evidence shows that Maduro and his Chavista political movement have played major roles in facilitating organised crime and narcotrafficking in Venezuela. However, the indictment appears to stretch the concept of “narcoterrorism”, which is used to link drug proceeds to the financing of terrorism. There is no evidence that the Cartel of the Suns – the informal name for a loose network of military officers and government officials engaged in competition over cocaine trafficking routes – is directly engaged in terrorism. Instead, the US government makes the case that the accused were part of a conspiracy that worked with the FARC to turn Venezuela into a transshipment centre for moving cocaine from Colombia to the US, thereby financing FARC terror activities.

Moreover, although the indictment alleges the Venezuelan officials’ activities in narcoterrorism and related crimes “since at least 1999,” this is not reflected in most prior public US declarations. The US Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM) annual posture statements, which document the combatant command’s priorities in South America, mention “narcoterrorism” 7 times between 2001 and 2017—but always in reference to Peru and Colombia. The 2018 statement mentions the term once, superficially, in relation to Venezuela, while the 2020 Posture Statement asserts, “Maduro has allowed Venezuela to become a safe haven for the ELN, FARC dissidents, and drug traffickers while the Venezuelan people starve”. If Maduro were facilitating a “narco-terrorist” government, it seems likely that more posture statements in the past would have mentioned this pressing concern, à la Colombia or Peru.

The US War of Attrition

Regardless, setting aside the exact nature of the charges and their legal merits, US actions clearly reflect a calculation that Maduro’s government is vulnerable. Days after the narco-trafficking charges, the US State Department released a proposed “Democratic Transition Framework for Venezuela” in which both Maduro and Guaidó would step aside to allow a new council of state to preside over presidential elections. Unfortunately, coming on the heels of the indictments, Maduro quickly rejected the framework – something likely to happen to any US-proposed plan.

However, the US government may see this as a war of attrition. Economic sanctions have helped squeeze the economy while the recent crash in oil prices has further reduced revenues – oil proceeds have traditionally accounted for the vast majority of Venezuela’s export earnings and state finances. Further, this comes against the backdrop of the pandemic. Venezuela has reported only a small number of cases, but it is one of the worst prepared countries in the world to deal with COVID‑19. As a result, in reference to the indictment, Attorney General Barr said the timing was right precisely because “people are suffering.”

There are further examples of the US exercising maximum pressure. At his own COVID‑19 briefing on 1 April, President Donald Trump announced that the United States was launching “enhanced counternarcotics operations” in the Caribbean near Venezuela, the scale of which is particularly unusual for the region. Later in April, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the US Treasury issued licenses for Chevron and service operators in Venezuela to stay until December 1, 2020, but it also barred the enterprises from new oil drilling, extraction, refining, or capital expenditures. In short, US policymakers are betting that Maduro will be unable to outlast all these obstacles.

For his part, Maduro has already created more problems. In his scramble to quell growing discontent and protests over the affordability of goods and a gasoline shortage, he reinstated price control measures after they had been relaxed starting last year. This probably signals an increase in food scarcity and hunger, and it could increase domestic pressure for political change. Adding to this, Venezuela will have to confront the wave of migrants returning from a locked-down Colombia.

The US is not looking to the long term

One immediate effect the indictment had was to scuttle preliminary talks between Maduro and Guaidó over a partial truce that would allow them to make a joint appeal for international aid to deal with COVID‑19. This obviously does not augur well for the country’s immediate future or its preparation for the arrival of the pandemic. Official data are unreliable, but it appears that Venezuela has yet to fully reckon with the spread of COVID‑19. The long-term implications are almost as gloomy. The new strategy seemingly takes a negotiated solution to the country’s political crisis permanently off the table by further raising the exit costs for Maduro and his cronies.

As history has shown, the US has been much more effective at removing foreign dictators than rebuilding those countries. Consistent with this, the broader US strategy seems single-mindedly focused on removing Maduro rather than using the type of diplomacy and concessions that would help to re-establish democracy. So while the depth of the country’s economic and humanitarian crisis in combination with sustained US pressure might destabilise Maduro, a successful democratic transition will require some type of negotiated settlement as it did in South Africa after apartheid, in Eastern European democracies after the Cold War, and in Latin America after the dictatorships of the 1970s. That has not been the US focus.

Regardless of the political outcome, Venezuela’s massive economic and humanitarian crisis is likely to grow worse in the months ahead. Whoever governs will have their hands full.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This post was originally publish by LSE US Politics and Policy blog

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Thank you for update. Please advise an oil deal with Aruba on 28 March after VP visited Trinidad on 27 March.