Frustrated Mexicans provoked a left-wing populist landslide in 2018 after the centre-right neoliberal consensus failed. The emergence of insurgents like Jaime ‘El Bronco’ Rodríguez and the FRENAAA movement suggests that voters could easily flock to the far right in 2024 if they feel that AMLO has failed them too, writes Rodrigo Aguilera.

Frustrated Mexicans provoked a left-wing populist landslide in 2018 after the centre-right neoliberal consensus failed. The emergence of insurgents like Jaime ‘El Bronco’ Rodríguez and the FRENAAA movement suggests that voters could easily flock to the far right in 2024 if they feel that AMLO has failed them too, writes Rodrigo Aguilera.

The rise of far-right populist regimes in liberal democracies has been one of the most troubling political trends over the past decade, and it still shows no sign of abating. With its long history of populism (from both the left and right), it is no surprise that Latin America has once again fallen under the populist spell, as evidenced most clearly by the success of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil.

Concerns that politicians like Bolsonaro could set a template for others to follow are fuelled by other factors such as the rise of evangelicalism, opposition to left-wing populism, and the prevalence of socially conservative attitudes in the region. Populism also tends to arise in the wake of crises, with the ongoing pandemic and associated recession providing fertile ground.

Yet, on paper at least, Mexico would appear one of the Latin American countries least susceptible to far-right populism. For starters, it recently elected a left-wing populist government following decades of discontent with its centre-right administrations, It also lacks any modern historical antecedent to far-right populism.

The country’s last “true” 20th century populist was Lázaro Cárdenas (1935-40), who actually helped solidify the institutional underpinnings of Mexico’s one-party regime: a rather un-populist thing to do. His policies were also largely redistributive in nature, and so more in line with left populism. Although Mexico joined the rest of Latin America on the free market bandwagon in the 1980s, even then it avoided the personalistic neoliberal populism seen in countries like Brazil under Collor de Mello, Peru under Fujimori, and Argentina under Menem.

Green shoots of radicalism: Jaime ‘El Bronco’ Rodríguez

Despite the lack of historical precedent, there are incipient signs of the kind of far-right attitudes that propelled Bolsonaro to power in Mexico.

An early warning shot came in the form of Jaime “El Bronco” Rodríguez, a businessman who successfully ran to become governor of Nuevo León in 2016, one of Mexico’s most affluent and economically important states. That he did so as an independent was a particularly impressive achievement, and behind it lay his self-styling as a kind of free-market caudillo, or strongman. Though more likely to be seen on horseback than in a pinstripe suit during his campaign, he still managed to appeal to his state’s entrepreneurial spirit. At the same time, however, his rugged image relied on highly sexist and homophobic views, punitive attitudes towards crime, and a personalistic style of leadership that all come straight from the populist playbook.

Rodríguez was not only the first independent governor in modern Mexican history, he also ran for president in 2018 and managed to obtain the largest vote share of any minority candidate ever (5.2%). In an election that was largely defined by support or opposition to Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), Rodríguez’s result should be taken more seriously than it has been to date.

Rodríguez’s template is not new. It was strongly influenced by that of Vicente Fox, the man who managed in 2001 to break the Institutional Revolutionary Party’s 71-year stranglehold on power. Fox was also known for his rancher get-up, colloquial mannerisms, social conservatism, and free-market tendencies. Unlike Rodríguez, however, Fox ran under the banner of the established National Action Party (PAN). And, unlike most populists, he attempted to shift power away from the presidency rather than towards it.

Far-right extremism from the grassroots: the National Anti-AMLO Front

Much like López Obrador, Rodríguez plays the outsider even though the clothes don’t really fit: in reality El Bronco was a lifelong member of the PRI until he ran for governor. But even if this brand of populism was able to emerge from such a traditional political background, there are signs that far-right populism could also emerge from the grassroots. The ongoing protest movement against López Obrador is representative of this possibility, and it shows some highly troubling signs of extremism that go far beyond simply offering a voice to AMLO’s detractors.

The “Anti-AMLO” movement began soon after his election and has largely focused on portraying him as a “Bolivarian dictator” who intends to turn Mexico into a communist state; this tactic of linking AMLO to Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez has been used successfully since the fractious 2006 presidential race against Felipe Calderón. Anti-AMLO protests have taken place repeatedly in Mexico City and other major cities, but most of the protesters are affluent white Mexicans demanding López Obrador’s resignation. Since the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, many of these protests have taken the form of motorised processions, echoing the tactics of Spain’s far-right political party Vox.

At first glance, the protests have reflected little more than an almost comical disconnect between Mexican elites and the rest of the population. It was not uncommon, for example, to see protesters calling López Obrador’s supporters scroungers because of their support for welfarist policies, yet all the while their own signs were being carried by their maids. Attendance at these protests has also been far smaller than expected, and the numbers certainly pale in comparison with AMLO’s own massive rallies. Many of the signs also bore religious slogans.

More recently, protesters have set up tents on a supposedly permanent basis in Mexico City’s main square, just as López Obrador’s followers did after the disputed 2006 election. This time around, however, most of the tents have been found to be empty.

Despite this, the anti-AMLO movement has become more organised, with the National Anti-AMLO Front (FRENAAA) at the forefront of the recent tent protest. Its leader and founder, Gilberto Lozano, is a white businessman from Monterrey who is known for misogynist, homophobic, and racist comments. Given this backstory, it would be easy to dismiss FRENAAA as a virulently anti-left segment of the Mexican elite appealinng especially to a Mexican north that has often felt culturally and racially separate (not least when the #Nortexit hashtag calling for northern Mexico’s independence started to trend on Twitter earlier this year). But even if someone like Lozano is unlikely ever to gain mass support, the sentiments that he plays on are far more widespread.

Mexico’s alt-right

Neither has Mexico, which boasts the fifth largest Facebook user base in the world, escaped the emergence of internet-based hate speech and far-right indoctrination. A passing glance at the comments section of most Mexican news sites reveals an endless stream of vitriolic rants on politics, even when the subject of the article itself is not political. This is especially true of themes that relate to identity politics, where you can find unrestrained homophobia, transphobia, misogyny, anti-Semitism, and the rest. As I noted in a 2017 article for the Huffington Post, there are many similarities between Mexicans’ online behaviour and that of the alt-right in the United States, including the widespread use of memes and coordinated mass trolling of the type that emerges from sites like 4Chan. Things have only gotten worse in recent years.

These attitudes and behaviours are not neatly split along ideological lines: López Obrador’s supporters frequently engage in the same kinds of hate speech as his opponents. It certainly does not help that López Obrador himself is a social conservative and has often been at odds with groups that typically enjoy the support of the left, such as feminists. It appears that even in a country with such stark political divisions, the one thing that can unite most Mexicans is a venomous hostility to identity politics. And as we know from the alt-right, this is often the most effective way to introduce people to a wider range of right-wing views.

A far-right populist in 2024?

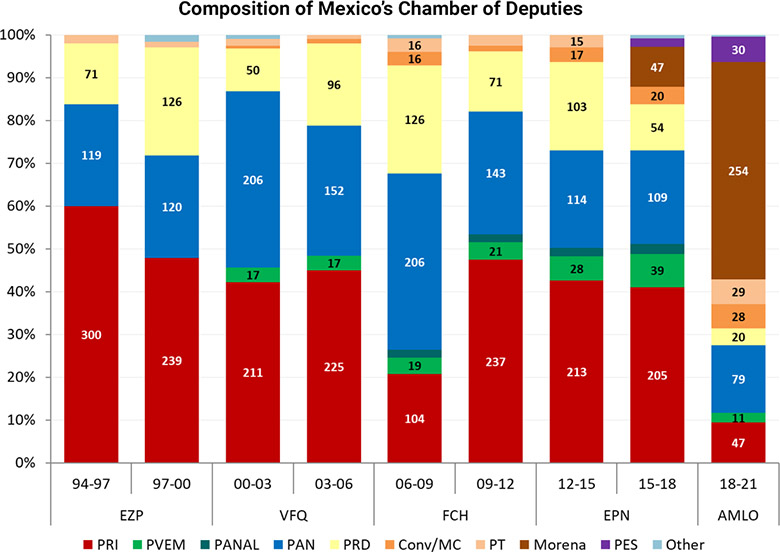

The belief that far right populism could not make inroads into Mexico’s highly entrenched party system ignores the fact that the 2018 election dramatically reshaped Mexico’s political system after three decades of rigid tri-partisanship (as illustrated below). If voters remain as angry in 2024 as they were in 2018, it is far from inconceivable to think that independent or minority candidates, especially those pushing a populist message, could take a bigger slice of the pie than ever before.

EZP = Ernesto Zedillo, VFQ = Vicente Fox, FCH = Felipe Calderón, EPN = Enrique Peña Nieto, AMLO = Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador. Note: based on seats at the start of each legislative period.The appeal of such candidates will largely depend on their image and messaging. Rodríguez’s cowboy antics may appeal to northerners, but most other Mexicans would be wary of a second Vicente Fox, whose presidency is largely seen as a failure. Lozano and his FRENAAA supporters, meanwhile, are too white and too affluent to represent most Mexicans, although a desperate PAN may be tempted to embrace someone like him if it more moderate potential candidates come across as insipid and unappealing, as they want to avoid a repeat of the electoral losses of 2012 and 2018. Modern far right populism is staunchly economically liberal (if not borderline libertarian), but a free-market fundamentalist message remains unlikely to appeal to an electorate that flatly rejected three decades of neoliberalism in 2018.

Instead, a successful far right populist could present a cocktail of grievances: economic crisis (particularly if López Obrador’s economic agenda fails), a broken society afflicted by crime, and a loss of national identity and values. This has proven to be a winning formula for virtually every successful far-right populist of recent years, and there is no reason to think it wouldn’t work in Mexico too. The Janus-faced discourse of far-right populism – claiming to be the voice of the people while acting for the benefit of elites – will also ensure plentiful support from the more affluent sectors of Mexican society.

Ultimately, we have already seen frustrated Mexicans provoke a left-wing populist landslide in 2018 after the disappointments of the centre-right neoliberal consensus. It is not inconceivable that they will flock to the far right if they feel that AMLO’s leftist transformation of Mexico has failed them too.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or LSE

• This article draws on ideas about the emergence of far-right populism drawn from the author’s book The Glass-Half Empty: Debunking the Myth of Progress in the Twenty-First Century (Repeater Books, 2020)

• Follow Rodrigo Aguilera on Twitter at: @raguileramx

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Excellent points made in your article Mr. Aguilera. I would object in just two minor points.

Your article fails to touch on the power of the third tech revolution that now, more than ever is quickly transforming the very notion of the “nation-state” – a relatively recent concept in terms of Sócio-political and economic groups that share together a territory and certain historical and identity (loosely and arguably here if course) traits. The impact of tech is for example, positioning global currencies which value is less and less attached to more traditional determinants of their value such as gold, petro, GDP numbers, and other more tangible concepts of value. Too, commerce, and many other matters that affect and effect our daily lives are every day less attached to a specific territory as we can now clearly move, do, undo, explore and a myriad of actions from the comfort of our own homes.

Economies are adapting and yet, the challenge with the most recent events remain daunting. López Obrador, not as much a populist as we often tend to presume compared to many other candidates from both left or right, has had very room to maneuver and show the real pinch – good or bad – of his policies. I even feel that the global re-order of axis and centers at many levels came a bit too fast (and furious!) for him and many others in governments to adapt quickly. That, is just an opinion.

Of course, nobody asked for my opinion but then one sees global economies falling behind as for months some of us forewarned of a deep crisis that would/could and did greatly affect many sectors – the most disenfranchised of course – behind in the gap of knowledge, access, and opportunities.

From my standpoint, there are many people not currently working that are still eager to have economies re-open to become active members of a healthy economy and pay rather than “take” from the taxes that make governments run.

One last quick matter: While economies have not yet re-opened, there are already many alarm bells sounding talking about “bubbles”. There was a speaker at the school I attended in 2007 who happened to be US Treasury for most of the “warnings” about the bubbles (Alan Greenspan) and yet, he managed to hold what seemed to be a strong economy until we saw countless of people lose their life savings as well as a great deal of graduates unable to be placed in jobs for months if not years during the financial crisis of 2008. In retrospect, our generation, should still have that crisis very fresh in our memories.

Once Lehman Brothers and others collapsed, many of us struggled a lot to find paying jobs despite attending certain schools or graduating with particular grades. I don’t know how this new economic slowdown (to name it in a softer way) will play out in the longer term. After all, I am not truly an Economist.

For the human rights and hoping to avert unforeseen humanitarian problems like hunger where it may not have been before however (ie. how many soup kitchens operate today vs in December of 2019 could be just one set of variables worth exploring for economists who want to understand if hunger can or will be an issue.) Children specially, shouldn’t go without food to eat.

Dear sir, many children do go to soup kitchens when their homes are. Not well suited for a nutritious warm meal. They need you all. Thank you.

With all respect.

Eduardo Guzman, MSc Global Politics.

“a free-market fundamentalist message remains unlikely to appeal to an electorate that flatly rejected three decades of neoliberalism in 2018.”

They’ll come crawling back, especially with oil prices stuck where they are or lower. You don’t get to say ‘no’ to free markets anymore than you get to say no to gravity. Reality is not up for a vote.

Mr. Aguilera. To compare the Mexican middle class protests with radical right is far fetch and a simplistic analysis.

It is very shallow and it has nothing to do what it is happening in the United States or Europe.

The middle classes in Mexico are a minority and now they are fighting for the survival

Contrary to what happened in Venezuela. The middle classes in Mexico are asking the government to respect their rights. All the policies in Mexico are directed to the Mega rich or to the poor . For the first time in Mexico history of Mexico the middle classes are fighting for survival. To equivalate that to radical right is a total deserving for this interesting and unique social phenomena and for the struggling social sector that has always been forgotten in Mexico/