Over the last decade and a half, figures for migrant kidnappings in Mexico have remained persistently high. Yet little attention has been paid to the diversity of actors participating in these illicit acts – in particular the role of women, writes Caitlyn Yates (University of British Columbia).

Over the last decade and a half, figures for migrant kidnappings in Mexico have remained persistently high. Yet little attention has been paid to the diversity of actors participating in these illicit acts – in particular the role of women, writes Caitlyn Yates (University of British Columbia).

In 2009, “La Madre” ran a migrant shelter in Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz, Mexico, where she offered migrants the kind of welcome that you might expect given her maternal nickname. But this classic, caring feminine persona was just a front. Instead of providing aid, La Madre was funnelling these migrants towards the criminal group Los Zetas, who would hold them until family members agreed to pay a ransom for their release.

In recent years, both the media and policymakers have paid increasing attention to the victims of migrant kidnapping in Mexico, yet little attention is paid to the actual dynamics of kidnapping rings themselves. With less than 1% of crimes against migrants ever brought before a judge, it is critical to first understand the structures and actors participating in these illicit activities if the country is to make real headway in tackling them.

As part of our recent collaborative research, we used media reports and official state-level data to create a database of 388 migrant kidnapping incidents throughout Mexico between 2006 and the first half of 2018. In doing so, we found that women consistently played significant roles in migrant kidnapping rings despite the lack of public and law-enforcement attention on women as illicit actors in these high-impact crimes.

The dynamics of migrant kidnapping

La Madre’s story is not an isolated incident. Rather, it is indicative of the everyday security concerns that migrants face as they transit through Mexico. Though data on the prevalence of migrant kidnappings in Mexico are sparse, Amnesty International estimated in 2014 that up to 20,000 migrants are kidnapped each year. This figure complements tallies with our own estimate that anywhere between 200,000 and 250,000 migrants may have been kidnapped over the 12 years covered in our research.

Migrant kidnappings tend to proceed in four distinct phases:

- An individual or individuals must gain physical control over the victim by physically coercing migrants or luring them with false promises.

- The perpetrators must maintain control of migrants within stash houses while still providing migrants with at least some degree of care, including food and water.

- Kidnappers request ransom payments via phone, and payments are retrieved from banks or wire-transfer locations.

- Migrants are released from the stash house following a successful ransom payment. If their family cannot pay, they may be left in the stash house, released nonetheless, or killed.

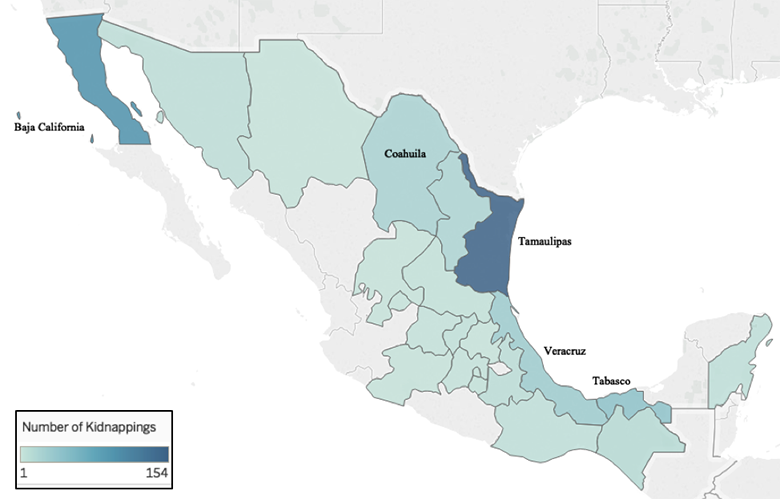

Despite these trends, there is no such thing as a standard migrant kidnapping, especially when it comes to the actors involved. In each region of Mexico migrant kidnappings take on different forms and frequencies, with varied modes of operation, perpetrators, and migrant demographics.

For instance, in northeastern Mexico – including along the border with Texas – migrant kidnapping rings frequently involved criminal groups like Los Zetas and factions of the Gulf Cartel. In southern Mexico, meanwhile, kidnapping rings tended to be much smaller, and we only came across two instances where organised criminal groups conducted kidnappings in that region. The average number of individuals detained per incident in our database was three, while the number of perpetrators detained ranged from zero to 15.

Overall, some kidnapping rings are run by smaller groups of family members, friends, police units, or local opportunists. Criminal groups do also take part in migrant kidnapping activities in Mexico, however, and this is especially true of northern Mexico.

The gendered dynamics of migrant kidnapping

Just as the structure of kidnapping rings often varies, so too do the demographic profiles of kidnappers themselves. These rings are frequently depicted as male-dominated, yet women were present in 30% of all of the migrant kidnapping rings in our dataset. Women’s roles and responsibilities did tend to fall along gendered lines, however, and within four broad categories.

First, some women served as intermediaries in recruiting or deceiving potential victims. Here, women could often garner trust more easily when engaging migrants, or at least arouse less suspicion than men. About 35% of the women in our database operated as intermediaries. La Madre’s role of luring migrants into a shelter before handing them off to Los Zetas is one such example. In other cases, women were also former migrants themselves, which bolstered their ability to gain the trust of potential victims.

Second, women were also charged with providing services within stash houses, such as cooking, cleaning, or making ransom calls to migrants’ families. Approximately one quarter of the female kidnappers in our study participated as service providers in this way. Women sometimes participated willingly, but many women in these positions were also former migrants or kidnapping victims that had been forced into performing these tasks.

Third, women also collected ransom money from local banks or wire-transfer locations in approximately 35% of our cases. We postulated that women were tasked as fee collectors because they may come across as less suspicious than men when retrieving large sums of wired money. In one incident, roles within a particular ring were split right down the middle, with the men acting as migrant smugglers and the women participating exclusively in payment retrieval.

Finally, and less commonly, women directly participated in organising operations or delegating orders. The enforcer role only showed up in two of the cases in our study, and in both cases delegation by women was carried out in tandem with men. Women also appeared to adopt enforcer roles only in smaller kidnapping rings rather than in operations perpetrated by organised criminal groups. In both of the cases in question, the women involved were related to the men running the kidnapping rings.

Overall, women play frequently neglected but operationally important roles in migrant kidnapping rings. But they are generally relegated to gendered tasks which exploit women’s supposed abilities to gain the confidence of migrant and avoid suspicion from authorities.

State responses to migrant kidnapping

Migrant kidnappings in Mexico occur throughout the country and are carried out by a variety of actors. But there is currently little chance that they will have formal repercussions, as Mexico has an estimated 99% impunity rate for crimes committed against migrants. Worse yet, these figures excludes the huge number of cases that go unreported, with transit migrants often being wary of the authorities because of their irregular migration status.

In 2015, Mexico’s Office of the Attorney General created a Specialised Unit of Investigation for Crimes Committed Against Migrants. But five years into the unit’s mandate, it remains wholly underfunded and has failed to reduce this staggering rate of impunity. In 2019, the unit registered 383 cases, but just three (0.78%) went before a judge.

There are numerous challenges to addressing migrant kidnapping, but one of the first must be to address the diversity of actors and variety of structures present in Mexican kidnapping rings. Most importantly of all, however, migrant kidnapping needs to be made a priority at the national and even the regional level. If this crime continues to linger in the shadows, migrant kidnappings will continue at the same alarming rate that we have seen in recent years. It is migrants and their families that will pay the price.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Banner image: Digital21/Shutterstock.com

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting