In October 2020, the people of Chile voted overwhelmingly to create a new constitution. If we are to capitalise on this historic opportunity, we Chileans must dare to dream of bold new ways to address our problems and guide our institutions. Focusing on the environment, happiness, and economies of care and meaning would be a huge step in the right direction writes María Carrasco (Entramada and Atlantic Fellows for Social and Economic Equity).

In October 2020, the people of Chile voted overwhelmingly to create a new constitution. If we are to capitalise on this historic opportunity, we Chileans must dare to dream of bold new ways to address our problems and guide our institutions. Focusing on the environment, happiness, and economies of care and meaning would be a huge step in the right direction writes María Carrasco (Entramada and Atlantic Fellows for Social and Economic Equity).

• Disponible también en español

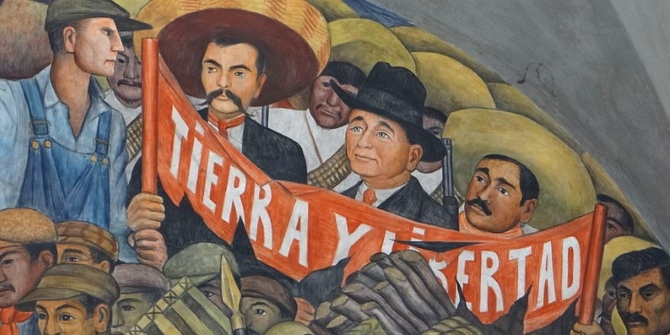

We are living through a historic moment: soon, Chile will have a new constitution that replaces the one written in the era of dictator Augusto Pinochet. But what does this momentous event mean? Are we deciding what “constitutes” us as a society? While the constituent process naturally requires us to define the rules that govern rights and duties, it could also be a space in which societies debate the beliefs and frameworks that define their daily behaviours, their relationships with others, and ways of life compatible with the values we might wish our national constitution to underscore.

If we are unable to put forward concepts that address the key challenges that we face, such as ecological exploitation and social fragmentation, it will be no easy task to create the conditions for a more equitable and prosperous society.

This is why it is vital for our future that we dare to advance concepts that can tackle the fundamental problems of our society and guide our institutions towards standards that we have long yearned to see upheld. Some concepts we should consider include ecocentrism, happiness, and the promotion of economies of care and of meaning.

Ecocentrism requires us to look at nature as a living being with its own rights. This will mean making nature a constituent part of our collective lives, protecting it and punishing attacks against it, just as we do with human life.

In 2008, Ecuador became one of the first countries in the world to make Nature a legal subject. Article 71 of the country’s constitution states that:

[Nature] has the right to complete respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its cycles of life, structure, functions, and evolutionary processes. Any person, community, people, or nationality can demand that public authorities fulfil the rights of Nature…

This would mean that setting the recent and apparently intentional Quilpué forest fire in Chile’s Valparaíso region, for example, would be punished just as harshly as a murder. Today, our laws rest on the idea that human beings are superior to nature, and so human losses are considered more serious than the destruction of 4,000 hectares of forest, despite the huge impact on the lives of those living nearby. Forests are a fountain of life: aside from the wildlife within them, they also hold the water reserves of the communities living in surrounding areas. Therefore, an attack on a forest is also an attack on all those who live around it, and on future generations.

Furthermore, the concept of ecocentrism integrates the vision of our indigenous peoples, where nature is the source not only of life but also a profound sense of connection. Within such a framework, it becomes possible to imagine that we should leave certain zones protected because our native peoples consider them sacred. This requires us to start promoting a vision of development that is quite different from the current extractive model that characterises primary-export economies such as Chile’s.

Taking happiness as another major guiding concept would allow us to look at our day-to-day lives and our social structures from a new perspective. Of course, the concept of happiness is open to debate, and it has a significant subjective element. But in light of the insights of positive psychology and the many studies on happiness, including the annual World Happiness Report for the United Nations, we have been able to identify the conditions most likely to generate enduring wellbeing: good mental health, spaces for recreation (where nature plays a fundamental role), a just and dependable society, connectedness to a community, and healthy and active social relationships.

If happiness and the conditions required to achieve it are a matter of public interest, we can begin to shape a framework of priorities. If, for example, mental health is necessary for happiness and subjective wellbeing, access to mental health services should be guaranteed, just as we need access to natural settings for rest and recreation.

In fact, in 2011 the UN unanimously approved a motion that recognised the pursuit of happiness as a fundamental human goal, and stated that member states should therefore bring about the conditions to achieve it. In a similar vein and throughout history, various countries have incorporated happiness into their constitutions: amongst others, the United States (1776), France (in the Declaration of the Rights of Man in 1789, and underpinning the French Constitution of 1791), Japan (1947) and Bhutan (2008).

Taking happiness as a guiding concept leads us to think about other aspects of being human, to take inspiration from sources of meaning beyond the workplace, to develop our capacity for leisure, to take time to become part of a community, to care for the environment, and to engage in other pursuits, including spiritual ones.

All of which brings us to the third guiding concept we must dare to dream of: the promotion of economies of care and meaning. According to feminist economist Corina Rodríguez Enríquez, these terms refer to:

[All those] activities and practices necessary for people’s daily survival in the societies where they live. It includes self-care, direct care for others … provision of the preconditions in which care takes place … and management of care.

This means emphasising activities that have not been monetised even though they generate value, such as raising children. Science has demonstrated the crucial importance of child rearing in personal development, where it plays a greater role than socio-economic variables. To achieve healthy and prosperous societies, it is more important that our carers have the time, mental energy and tools to support our children’s development than that they have the money to buy objects that are not necessarily essential.

Caring for our older people, furthermore, is another focal point of care that profoundly affects our societies. In terms of socio-economic inequalities, those on higher incomes can pay for this kind of care in private or domestic settings without it affecting their quality of life. But those with low or no income can only offer their own unpaid and insecure labour, which has major impacts on their quality of life. Many families, in fact, have to decide who will stop working in order to take care of a family member. That said, in most cases it is vulnerable, unemployed women who end up carrying out that function, which further aggravates existing gender inequalities.

Thinking about societies of care leads us to strengthen the “meaning economy”, where our wellbeing springs from activities that connect us with our own essence, where we are no longer necessarily talking about production in material terms but instead about self-expression, art, health, spirituality, teaching and creativity. Care economies lead us to express the innate essence of our humanity, which is caring for others, whether it be humans, pets or the environment. Yet these intangible services tend to be seen as less valuable than extractive activities such as mining or fishing.

Taking responsibility for care as a society also leads us to fundamentally reconsider the fiscal consequences of inequality in terms of our tax structures and the allocation of public spending.

Of course, simply bearing these concepts in mind will not necessarily lead to greater happiness, gender equality, or respect for our ecosystem. But they do provide a framework that could enable better prioritisation of public policies and a redefinition of social policy. In Chile as elsewhere, if these policies were underwritten at a fundamental legal level, the state would be forced to rethink the economy and its own fiscal and developmental role within it. How else will we be able to ensure permanent protection for natural areas, riverbeds, and forests; to prioritise mental health, making nature an integral part of urban life and art a central pillar of prosperous communities; and to properly value care for sentient beings, human or otherwise?

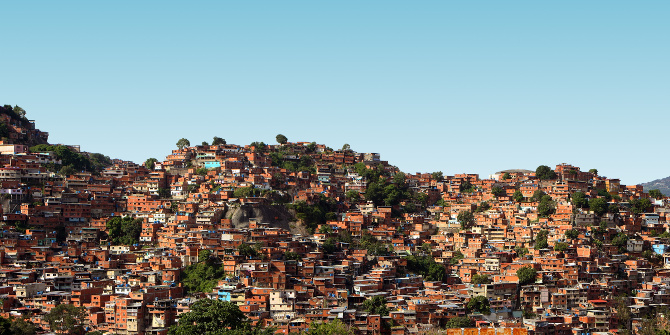

In recent years, research has begun to explore the intersection of social justice and environmental sustainability, whereby social inequalities are seemingly reproduced in the environmental arena, as Lucas Chancel has argued in his book Unsustainable Inequalities: Social Justice and the Environment. This makes sense: while the rich consume and pollute more than poorer people, it is the poor who are most affected. Take, for example, the Chilean municipalities of Til-Til, Petorca and Ventana: these high-poverty areas have suffered the ecological and social consequences of productive activities that generate wealth, but only for economic and professional elites who live at a safe distance, mainly in the capital, Santiago.

Simply put, if we included these guiding concepts in the new Chilean constitution, we would be taking on board ideas that are essential to our sustainable coexistence as a society. They would allow us to move away from the material concerns of so-called economic progress, and to emphasise real prosperity instead, by focusing on caring for our ecosystem and for all sentient beings, from their very beginnings to the end of their days.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This article post was first published on the Oxfam From Poverty to Power blog

• Translated by Asa Cusack

• Please read our comments policy before commenting