If Latin America is ever to shake off its label as “the most unequal place in the world”, it will need to stop focusing on the symptoms and attack the root causes, writes Amir Lebdioui (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre) as part of the Canning House Research Forum and building on the LSE Festival event Breaking the Inequality Mould.

If Latin America is ever to shake off its label as “the most unequal place in the world”, it will need to stop focusing on the symptoms and attack the root causes, writes Amir Lebdioui (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre) as part of the Canning House Research Forum and building on the LSE Festival event Breaking the Inequality Mould.

• Disponible también en español

• Também disponível em português

In Latin America, the richest 10% of people capture 54% of the national income, making it one of the most unequal regions in the world. But the ability of states to redistribute taxes or facilitate consumption amongst low-income groups may not be enough to sustainably reduce income inequality. These moves leave untouched the greater obstacles: limited productive capabilities and weak absorption of labour in value-added sectors.

Instead, policy efforts should focus on combining diversification to increase labour demand with improved employability for lower income groups. The region now needs to go beyond palliative solutions that target symptoms and instead attack the root causes. But how?

- Focusing more on pre-distribution inequality;

- Reducing commodity dependence;

- Using industrial policy more strategically;

- Going beyond conditional cash transfers given a paucity of production jobs;

- Accepting that inequality leads to economic instability and social unrest.

Pre-distribution inequality in Latin America

Instead of the usual focus on post-distribution inequality, the Latin American context requires a particular emphasis on pre-distribution inequalities (also known as pre-tax or market inequality). Though many social policies have managed to reduce poverty and inequality, existing productive structures create a constraint because Latin American inequality is the result of an uneven personal distribution of labour income – the split among wage earners – rather than a functional distribution of income – the classic split between labour and capital.

The author also presented his research on tackling inequality in Latin America as part of the 2021 LSE Festival on Shaping the Post-COVID World

The suitability of redistributive taxation for reducing inequality also depends on the scale of the reduction needed. In Latin America, redistributions and tax reforms are unlikely to lower the Gini coefficient to OECD levels because the initial income distribution is so uneven that even after a major fiscal shift won’t do the job, yet it may still have adverse effects on economic growth. Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela’s pre-tax Gini coefficients are all above 60, while those of OECD countries are mostly in the 40s or high 30s.

Export concentration, commodity dependence, and pre-distribution inequality

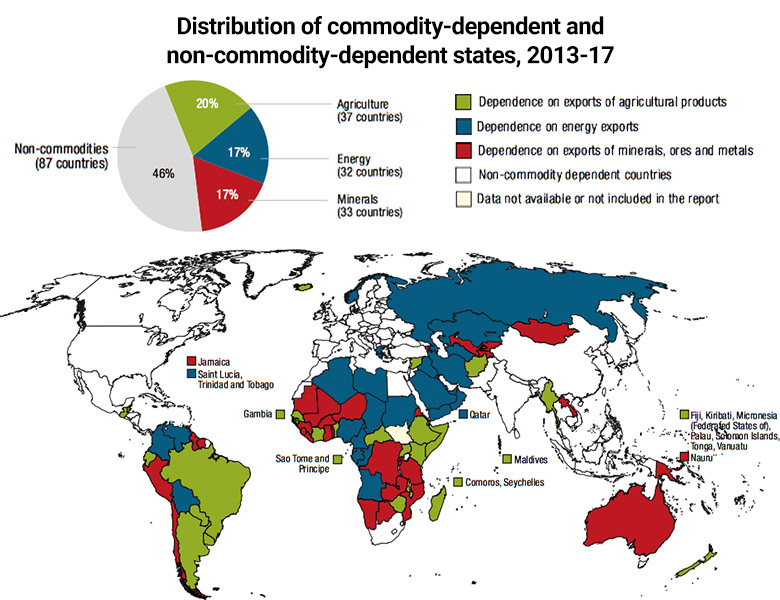

We also need to pay attention to the role of productive diversification in pre-distribution inequality. An overwhelming majority of Latin American countries remain dependent on fossil fuels, mining, or agricultural exports (see map below), albeit with subregional variations. Though few Central American countries are commodity-dependent, every single country in South America is, making it the most commodity-dependent region in the world.

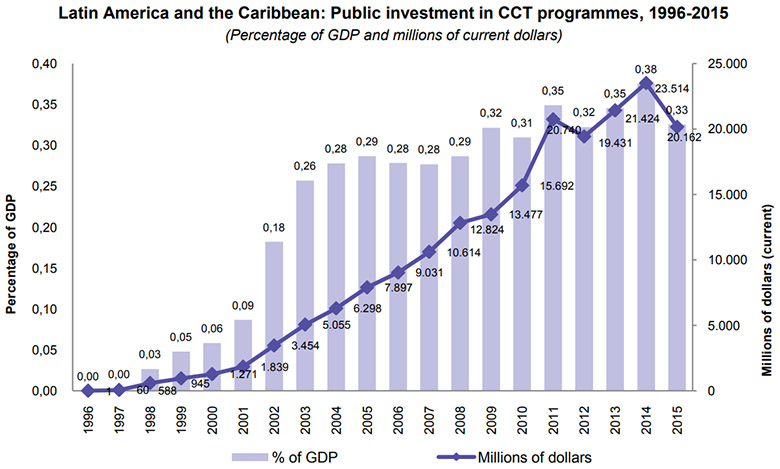

This matters because social spending is linked to commodity price volatility, with investment in social provisions and conditional cash transfer (CCT) programmes dropping off sharply after the 2014 collapse in commodity prices, for instance (illustrated below).

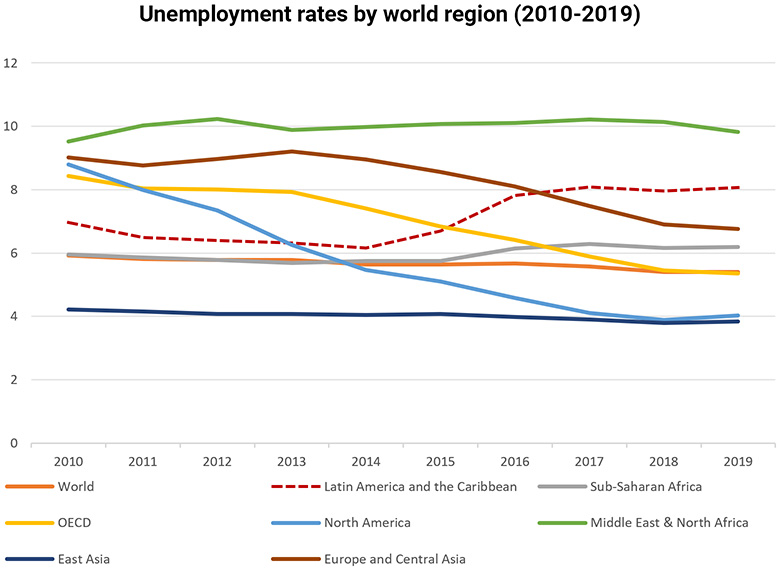

The 2014 oil-price collapse has also left producers in the region struggling to cover their costs, leading to a considerable dip in government revenues, reduced public investment, and slower growth. Lower commodity revenues more broadly have translated into higher unemployment rates across Latin America, as shown below.

The issue is that there can be no one-size-fits-all approach to inequality reduction. Solutions that work in France or Denmark may falter elsewhere, especially in the peculiar conditions of Latin American economies.

Learning to fish… in a fishless lake: the problem with relying on CCTs

Conditional cash transfers (CCTs) have become an increasingly popular weapon against inequality since their emergence in the mid-1990s in Brazil and Mexico. A CCT consists of a lump-sum cash transfer based on conditionalities that often relate to education (school attendance of a recipient’s children, for example) or health (receipt of vaccinations, say). CCTs that encourage schooling aim to help young beneficiaries acquire the human capital required to improve their employment outcomes. But without policies to stimulate export diversification and reduce commodity dependence, CCTs will never be enough to significantly reduce inequality on their own.

Many studies have criticised the CCT model not only for assuming that schooling will enable recipients to access available jobs, but also for neglecting to ask whether those jobs will even exist when young people enter the labour market. The reality is that many Latin American countries have low technological sophistication, limited areas of comparative advantage, and therefore few opportunities for skilled employment. In these contexts, for CCTs (and skill upgrades in general) to make sense, they need to be accompanied by the generation of productive jobs that are capable of absorbing skills into the labour market.

Brazil is a case in point. Though CCT programmes such as Bolsa Familia provide the poorest segments of the population with better access to education and health, students that have benefited from Bolsa Familia have faced significant difficulties in finding good-quality jobs. CCTs have a positive impact on inequality and poverty reduction by improving the supply of skilled labour, but only where they are properly integrated within more transformative programmes of social and economic development.

Policymakers in Latin America need to make sure there are fish in the lake before they start teaching people how to catch them.

Industrial policy, export diversification, and inequality reduction

In order to address these issues, state intervention should aim to generate productive employment not only from the supply side but also from the demand side. Coordinated education, social, and industrial policies can also help to generate demand for newly upskilled workers. Relying on market forces fails to break cycles of intergenerational inequalities, particularly when we factor in the impact of social norms, personal and professional networks, racial prejudice, and gender discrimination.

There is also an important role for export diversification and export sophistication, which underlines the need for pro-active industrial policies. Once a taboo topic associated with inefficiencies, abusive interventionism, and elite capture, industrial policy has recently had a resurgence and is now seen as a vital ingredient of economic diversification.

A growing body of credible evidence suggests that market forces alone are not enough to stimulate economic diversification. Rather, the acquisition of new comparative advantages across several now-diversified countries has often been underwritten by significant government intervention. Industrial policies – although often disguised – were also key to Chile’s export diversification up until the 1990s, when industrial-policy tools were gradually abandoned, leading to stagnation and then reversal of the export-diversification process.

Chile’s experience mirrors broader trends in the region as countries tried to follow the recipe for macroeconomic equilibrium prescribed by the famous “Washington Consensus” of the 1990s. But persistent growth problems, limited export diversification, rampant inequality rates, and the urgent need to generate new sources of employment now amply justify the return of industrial policy to the forefront of the policy agenda. Even though this return has begun, albeit in different ways from one country to the next, the efforts of most Latin American countries are sporadic and therefore no substitute for coherent development and industrial strategies.

Inequality and social unrest

Latin American countries also need to recognise that inequality reduction is a problem for everyone, including the elite. The waves of protests and social unrest across Latin America since 2019 are a clear indication of how income inequality can generate political instability, which in turns leads to a reduction in investment, revenues, and growth. To expand the classic trickle-down metaphor, if the top glass in the champagne pyramid gets too heavy and the bottom layer is too unstable, the whole edifice will collapse, and a lot of glasses will get smashed in the process.

For that reason, the quest for more inclusive development models in Latin America is an urgent one. As societies like Chile search for a new social pact, understanding that an economy is only as strong as its most vulnerable members is a lesson that must be learnt quickly.

Forever unequal? Only if we choose to let it happen.

The Canning House Forum is a partnership between the LSE Latin American and Caribbean Centre and Canning House that aims to promote research and policy engagement around the overarching theme of “The Future of Latin America and the Caribbean”.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Watch the author presenting his research on this topic at the 2021 LSE Festival on Shaping the Post-COVID World

• Please read our comments policy before commenting

Greater equity is an important social goal, but given that we are not too far from the end of economic growth and that we need to be planning for the stead state economy, I’m wondering what Amir’s thoughts are on how to ensure income equity as we plan for the steady state economy.