Mexico’s recent mid-term elections were widely seen as a referendum on the country’s polarising president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, and his National Regeneration Movement party (Morena). The opposition PAN-PRI-PRD coalition made important gains in the Chamber of Deputies, but the same parties were roundly beaten by Morena in a number of state governor races. Though this means that Morena will go into the 2024 election as a consolidated, nationwide political force, these results do also offer glimmers of hope for the opposition, writes Rodrigo Aguilera.

Mexico’s recent mid-term elections were widely seen as a referendum on the country’s polarising president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, and his National Regeneration Movement party (Morena). The opposition PAN-PRI-PRD coalition made important gains in the Chamber of Deputies, but the same parties were roundly beaten by Morena in a number of state governor races. Though this means that Morena will go into the 2024 election as a consolidated, nationwide political force, these results do also offer glimmers of hope for the opposition, writes Rodrigo Aguilera.

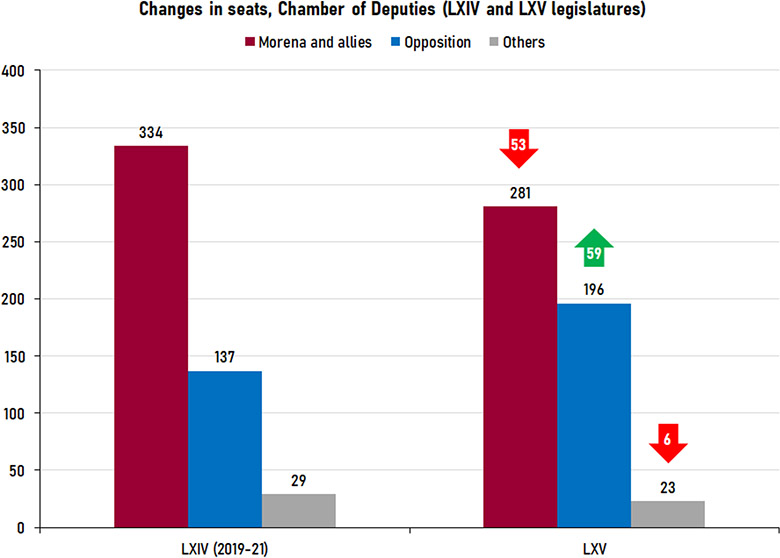

Though official legislative results have not yet been announced, Morena and its allies look set to lose around 50 seats in the 500-seat Chamber of Deputies, effectively robbing them of their 334-seat supermajority. This has considerable implications for policymaking as it means Morena will no longer be able to singlehandly carry out the kinds of constitutional changes that are invariably necessary for major reforms in Mexico (given the wide scope of the country’s constitution). That said, Morena and its allies will still comfortably retain an absolute majority (at least 251 seats), which will enable the passing of budgets and byelaws.

Morena majorities

Much has been said about Morena as a party (excluding its allies) not reaching the minimum number of seats for an absolute majority: according to an early estimate by the Instituto Nacional Electoral (INE), Morena is on course for a total of 190-202 seats in the Chamber. However, this is unlikely to pose a problem.

In the 2018 election, Morena on its own could not reach the threshold for an absolute majority, but this was ultimately achieved over the following months by transferring legislators from coalition partners into its own ranks. A total of 143 transfers have taken place during the current legislature, of which 112 were within Morena’s winning 2018 coalition (PT and PES). A subsequent alliance with the PVEM in 2019 ultimately enabled Morena to achieve its 334-seat supermajority.

This somewhat controversial tactic, known colloquially as “grasshopping” (chapulineo), is certain to be used again before the new legislature is inaugurated on 1 September 2021. This will enable Morena to keep control of the Chamber’s directive bodies and retain the power to fast-track legislation.

Morena sweeps the states but loses the capital

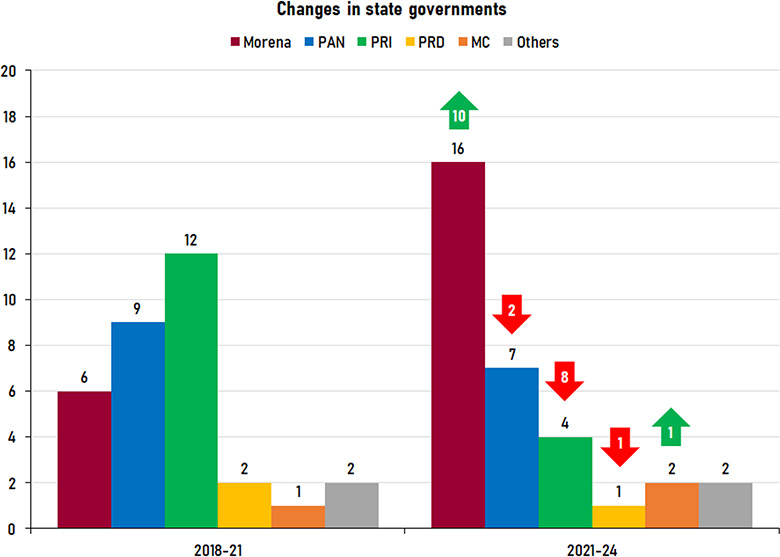

If Morena’s legislative performance was less impressive than party leaders might have hoped, its results in the 15 state governor elections held on 6 June represented nothing short of a landslide. Wins in 11 of these races have turned Morena into the country’s primary political force at the state level. The biggest loser, meanwhile, was the PRI, whose loss of eight governorships ended a state-level dominance that it had enjoyed since 1929.

More impressively, 10 of Morena’s wins were in states that it does not currently govern. A PT-PVEM coalition also managed to win San Luis Potosí, adding another state to the Morena-friendly side.

In contrast, the PAN managed to obtain two expected wins in states that it already controlled (Chihuahua and Queretaro) but suffered a net loss of two states, whereas the PRD made a net loss of one. Citizens’ Movement, an increasingly popular minority party, managed to obtain the only net win for the opposition, snatching the key economic state of Nuevo Leon, albeit with the highly controversial candidate Samuel García.

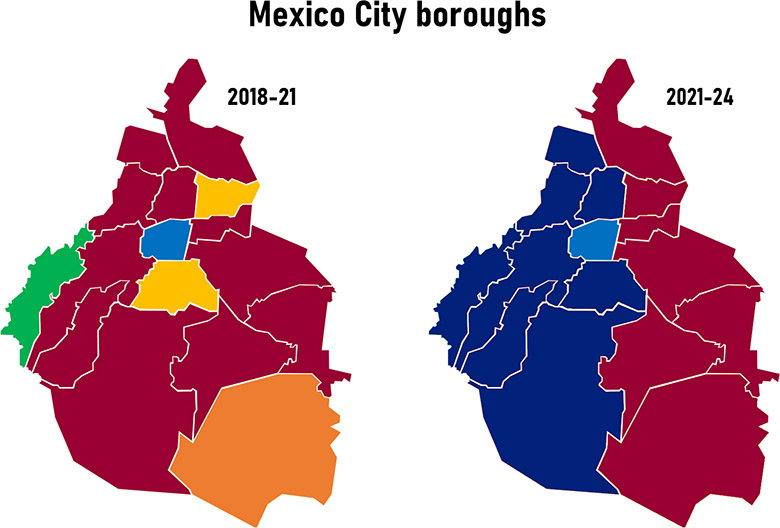

Among the hundreds of local government elections also held, the most notable were those in Mexico City, whose 16 boroughs (alcaldías) all held elections. Contrary to its historic reputation as a left-wing bastion, Morena suffered major setbacks in the capital, managing to retain only seven of the 11 boroughs that it held going into the elections. This is the first time since borough elections were first held in 2000 that a non-leftist party or coalition has won the majority of the capital’s boroughs.

Morena’s losses were entirely concentrated in the more affluent western boroughs, which further suggests a major socio-economic divide in terms of voting patterns in the city. The recent tragedy on Line 12 of the Mexico City metro on 3 May, which left 26 dead and was a major embarrassment for the Morena-led city government, may have also have had an impact on these results; numerous boroughs that seemed to be heading for Morena victories earlier in the campaign ended up being going to the opposition coalition.

Morena, the opposition, and Mexico’s 2024 elections

State election losses notwithstanding, the opposition should feel somewhat reassured that running as a coalition gives it a real opportunity to continue making gains against Morena in Congress – and possibly even a shot at the presidency in 2024.

With 45.4% of the vote in the legislative elections (at the time of writing), Morena and its allies’ share in Sunday’s election was actually higher than what they achieved in 2018 (43.6%). Yet this also resulted in a substantial loss of seats, most of which were at a district-level rather than from proportional representation. This reflects the ability of the opposition coalition to win districts that they would have otherwise lost if running separately.

A major wildcard will be Citizens’ Movement, which has more ideological commonality with the opposition. Combining its tally with the results for the wider opposition would amount to 46.7% of the vote, which is higher than the total achieved by Morena and its allies.

On the flip side, however, the massive gains by Morena in the states and its losses in Mexico City show that the old adage of the left-wing capital and the conservative, provincial regions is all but obsolete: the whole of the country is anyone’s game now.

Even in highly conservative Nuevo León, Morena’s candidate was ahead in the polls as late as March and was only derailed due to a scandal. And although the Mexico City losses carry heavy psychological impact, Morena’s victories in the states are far more relevant in bare numerical terms: around 23 more million people will be governed by Morena once the new governors are inaugurated.

Overall, Morena’s political hegemony in Mexico has ended, but not its dominance. A post-COVID return to normality and a rebounding economy could boost Morena’s prospects in 2021-24, and the personal popularity of López Obrador himself shows no signs of being dented despite numerous policy failures and a woeful pandemic response. Nor is the the opposition helped by its own lack of a coherent post-2024 agenda that isn’t based on romanticising a return to the same pre-2018 neoliberal policymaking that brought Morena to power in the first place.

Although these mid-terms offer the opposition a glimmer of hope for the future, as things stand the 2024 election will likely remain Morena’s to lose.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or LSE

• Follow Rodrigo Aguilera on Twitter at @raguileramx and on YouTube at ProgressumTV

• Rodrigo is the author of The Glass-Half Empty: Debunking the Myth of Progress in the Twenty-First Century (Repeater Books, 2020)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting