The Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Mexico has a fierce history of resistance, and the communities living there have their own infrastructural visions, which are rarely heard. In her research, Susanne Hofmann (LSE LACC) explores how residents interact with these projects while they advocate to not breaking with their ancestral cultural ties and ways of life.

In a press conference in early March 2023, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador revealed that Elon Musk, owner of the green tech company Tesla, had expressed interest in expanding his investments in Mexico. Word spread that Elon Musk was going to view potential development sites together with the Mexican president, paying special attention to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec region, where, at present, a multimodal transport corridor, the Corredor Interoceánico del Istmo de Tehuantepec (CIIT), is being developed. Memes started circulating in social media joking about Musk being stuck in one of the ongoing roadblocks in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, a region with a fierce history of resistance against both foreign invasion and imposed infrastructure projects. Blockades of motorways and the local train line are common ways to express discontent over grievances or planned government projects in the area.

Since the 19th century, the Isthmus of Tehuantepec has undergone a series of infrastructure works that sought to turn the region into an integrated transport link system, connecting the Atlantic with the Pacific Ocean, as well as the northern and southern states with the Yucatán Peninsula. The negative impacts of this endeavour of interregional integration on the environment and Indigenous communities were generally justified with the necessity of industrial expansion for national development, and promises of redistributive social programmes. A series of modifications of the constitution and federal law in the late 1990s led to an energy reform and the generation of Special Economic Zones (ZEE) in Mexico, which facilitated the large-scale capture of wind energy in the Isthmus with the help of foreign capital.

In defence of the land

There has often been little understanding of land defence or land-based social struggles in the global North. Particularly when they occur against what we think of as ‘modern’ or ‘green’ infrastructure projects. Land defenders in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec deplore those initiatives methodically weakened the generative, social character of the land, and promoted the external use and exploitation of the region’s natural assets.

The Infrastructure (Re)worldings podcast, is part of my research output about gender-based violence and security in the Interoceanic Industrial Corridor. In it, people affected by infrastructural interventions around the world share their experiences. Zapotec and Afro-descendant activist Rosa Marina Flores Cruz from Indigenous Futures was asked to explain the resistance against the generation of industrial wind parks in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec region that emerged in the early 2000s. Her answer highlights the similarity of so-called green investment projects with conventional ones:

“Well, what happens with the generation of renewable energy megaprojects, both wind and photovoltaic, as well as these natural gas pipelines, which are also postulated as transition energy, is that they follow the same scheme that has always been in place. A pattern of extractivist, large infrastructure projects that take damage to certain places, and others are the ones that obtain the benefits. So, this is what usually happens.” (Episode 12)

From an Indigenous perspective, the climate crisis is part of a cycle of collapse that was initiated with colonisation, and today’s efforts to mitigate the environmental crisis – based on intensified resource capture and extraction from territories located in the global South – acquire the character of ‘energy colonialism’. Infrastructure development tends to be promoted by state actors as a secure tool for the generation of economic benefits for local communities. However, in many cases, these works rely on prior changes in traditional landholding schemes, terminating existing collective rights. They also transform people’s existing relationships with land, plants, water and animals and, oftentimes, bring destruction. Understanding infrastructures as the spearhead of an ‘extractive-assimilation system’, through which communities experience environmental depletion and cultural breakdown, led some Indigenous scholars to label infrastructures themselves as ‘colonial technologies of invasion’.

Territory is not just land

For Zapotecs from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec like Rosa Marina Flores Cruz, territory is not just land. It carries the meaning of being shaped by the wind, the sea, the dust, by music, dance and fiesta. It is a community that generates life collectively. Territory allows for cultural existence and modes of subsistence to be reinvented all the time. Therefore, it is also a space from which collective resistance emerges. For Indigenous peoples, cultural survival has always meant simultaneously resisting and re-exist, requiring continual engagement in processes of regeneration of distinct ways of being and relating.

Indigenous and peasant communities in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec have their own visions, which are rarely heard. Community infrastructures that are designed, realised and maintained by locals and benefit them, are core to those visions. Beyond access to basic needs such as hospitals, schools, affordable electricity and internet access, a 2022 policy report mentions a desire for agricultural infrastructure that does not erase traditional, biodiverse forms of growing, such as the milpa or itinerant, mountain agriculture and seed exchange systems. In addition, an expansion of efficient irrigation systems, the detoxification of contaminated land and water sources, and the restoration of a regional passenger train that would allow local traders to sell their produce were core to a vision which could guarantee cultural survival.

Infrastructures to strengthen life and communities

Together with the Olmeca Refinery, the Maya Train and the Felipe Ángeles Airport, the Mexican government is promoting the Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (CIIT) as strategic infrastructure projects for national development. It includes the amplification of ports, extension of airports, track renewal for a cargo train, construction of a new highway and gas pipeline, as well as the development of ten industrial parks with logistical centres alongside the transport corridor.

The CIIT has been promoted as a viable alternative to the Panama Canal that would exploit the Isthmus’ geostrategic position for global commerce, and thereby automatically stimulate the local economy. Critics of the project fear, however, that the Interoceanic Corridor will benefit merely international trade, as well as boost the expansion of extractivist and predatory megaprojects in the region, such as mining, wind farms, hydroelectric dams, and commercial forestry and agroindustrial plantations.

The CIIT infrastructure project promotes an anachronistic, urban-industrial model of life that remains strongly reliant on hydrocarbons and petrochemical industries, whilst simultaneously integrating elements of ‘renewable’ or ‘fossil fuel 2.0’ industries. The term fossil fuel 2.0 highlights that many of the so-called ‘green’ or ‘sustainable’ technologies continue to rely on systematic processes of natural resource extraction, as well as the destructive use of land, forests and water in the global South, and the decomposition of mutual human-nature relationships.

Invoking the cannibal monster of an Anishinaabe legend, Winona LaDuke and Deborah Cowen speak of ‘Wiindigo infrastructures’, as the foundation for an “economic system predicated upon accumulation and dispossession, that denigrates the sacred in all of us.” Indigenous participants of the VDGSEGUR study have emphasised that infrastructure is ‘not just roads and cement’, but must be adequate for local living conditions, as well as ‘not break with cultural ties’ and ‘ways of life’.

Rejecting Wiindigo infrastructures, participants articulated the need for community infrastructures that would strengthen life, based on collective (re)building, mutual support and solidarity. Given direct access to financial means, strengthened communities could design and implement culturally appropriate infrastructures themselves that generate necessary, local productive activities, whilst guaranteeing both a sustainable management of natural resources and cultural survival.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the author rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Infrastructure (Re)worldings podcast explores how infrastructures make, unmake and remake worlds, and how they impact local communities, their social fabric, and relationships with the natural world around them. Listen here

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

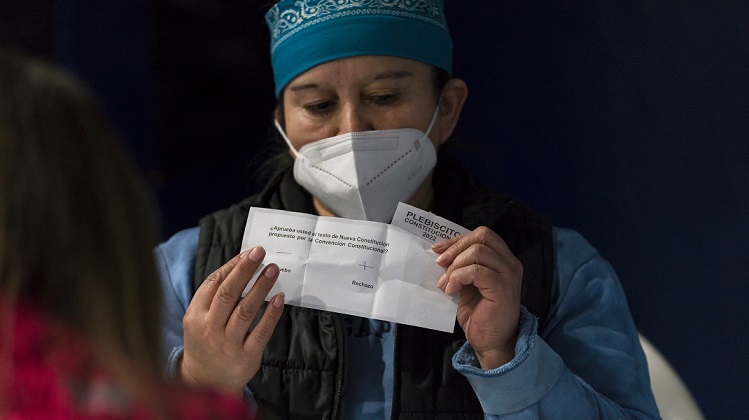

• Banner image: Protests in defence of the land in Mexico / Susanne Hofmann