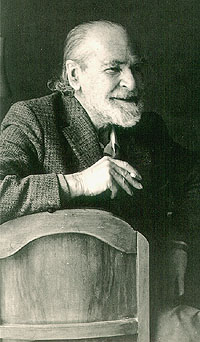

While the roll call of LSE alumni features notable journalists and novelists, one important literary figure associated with the School doesn’t feature, because he left without graduating, writes Dan Bennett. His name was Basil Bunting, and along with careers as a spy and sea captain, he was one of the key British poets of the twentieth century.

Born in 1900 in Newcastle upon Tyne, Bunting started at the School in October 1919, enrolling on a BSc in Economics. His first courses were in Geography, Economic History, Economic Theory, Local Government and Foreign Trade. A Quaker by upbringing, his pacifism had already resulted in him spending a spell in Wormwood Scrubs and Winchester prisons as a conscientious objector. Towards the end of his first year at the School, this independent streak reappeared, when he left London on an abortive visit to Communist Russia. A letter to the School, dated 4 January 1921 describes the adventure:

The reason for my journey was, I suppose, pure curiosity… I determined to spend a full year in Russia. Unhappily, the Norwegian police clapped me in prison for attempting to evade the passport officer, a crime I had no knowledge of committing, and afterwards deported me to England again. I never reached Russia at all.

Although Bunting had begged to be allowed to return to the School, it is clear from his file that he found it difficult to apply himself to his studies. Despite enrolling on courses in Principles of Economics, Theory of Public Finance and Economics of Great Powers, by 1922 he was excusing himself from studies with complaints of eye strains, and a later letter from the School Secretary to LSE co-founder Sidney Webb explains the wider problem:

I should find it very difficult myself to give a testimonial. Mr Bunting had ability, I believe but he did not attack his work at the School with real interest, and did not keep closely in touch with any member of the staff.

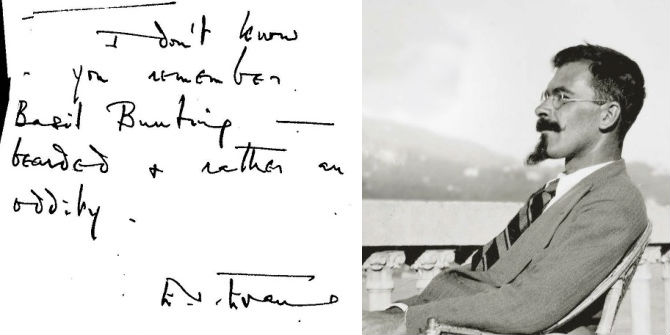

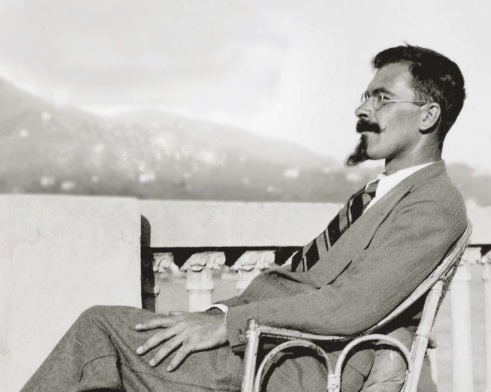

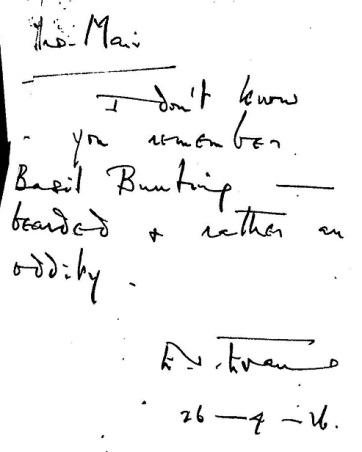

A note in his student file puts it more plainly:

I don’t know if you remember Basil Bunting – bearded & rather an oddity.

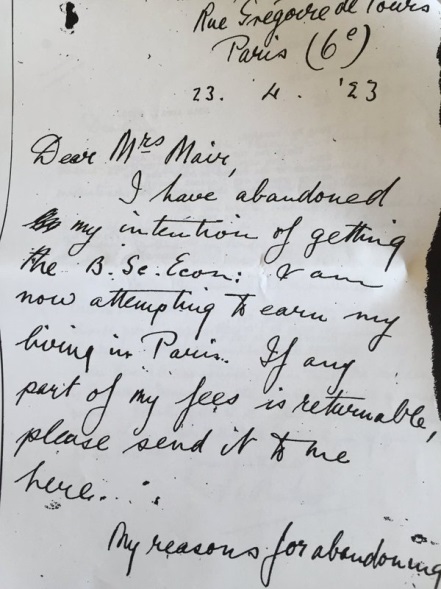

The School had offered London to Bunting, and with it exposure to Bohemians, social activists and journalists. His studies, too, would provide him with useful grounding, particularly in his later friendship with Ezra Pound, the ambitious American modernist poet, whose major work The Cantos has been described as “a verbal war against economic corruption”. (Pound’s dedication in his book Guide to Kulchur acclaims Bunting as a fellow “struggler in the desert”). Clearly, though, Bunting’s interests lay elsewhere. 1922 would be a definitive year in the cultural direction of the 20th century, seeing, amongst other events, the publication of T S Eliot’s The Wasteland and James Joyce’s Ulysses. The School had become a distraction to Bunting’s vocation as a poet. His last contact with LSE came in a letter written from Paris, on St George’s Day, 1923.

Dearest Mrs Mair

I have abandoned my intentions of getting the BSc Econ: I am now attempting to earn my living in Paris. If any part of my fees is returnable please send it to me here.

My reasons for abandoning the course are:

1) It interfered with my pursuit of literature

2) It did not seem to lead to any secure employment

3) It ceased to interest me for its own sake

4) It appeared (to me) to have turned several intelligent men into dullards, and I did not desire a similar fate.

I am now seeking employment as a bargee.

Despite his ambivalence, Bunting’s time at the School can be seen as formative, in that it set the haphazard pattern of his life. After time spent in France, Italy and the Canary Islands, he married and separated, and worked as a yacht captain in the United States. During World War II, he joined British Military Intelligence in Persia, continuing to work on the British Embassy staff in Tehran as a translator, until he was expelled in 1952. Finally, he returned to Newcastle, working on the Evening Chronicle until the 1960s.

While working here, Bunting met the younger poets Gael Turnbull, Tom Pickard and Jonathan Williams, all of whom were interested in writing in the modernist mode. In 1966, encouraged by this younger generation, he published his long poem Briggflatts — “an autobiography” concerning adolescent love and Northumbrian culture — which is now recognised as a classic of British modernism. He may never have finished his School degree, but his legacy in his chosen field would be assured, and his reputation both in England and America has continued to grow in the years since his death.