LSE Library hold the archives of alumnus and former government minister, Hugh Dalton. Student Alma Simba shares her experiences using Hugh’s diaries for research, on the centenary of the end of the war he was writing about. From opening and interpreting the archives to visiting the Imperial War Museum’s centenary exhibition, Alma writes about studying history and the fluidity of interpretation: making up with the past.

Hugh Dalton was an LSE alumnus and former lecturer, most remembered for his post-World War II position in the British Labour Party as the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Dalton’s life landmarks also include fighting in Italy during the First World War, serving in Churchill’s wartime coalition cabinet and environmental activism.

My task was to read through the archives on Hugh Dalton; this task coincided with various Remembrance events, plaques, podcasts, newspaper articles etc. being written about the 100-year anniversary of the end of World War I, in 2018. This felt like a relevant backdrop to how Dalton’s diary was read and analysed, as he wrote extensively on life during the First World War.

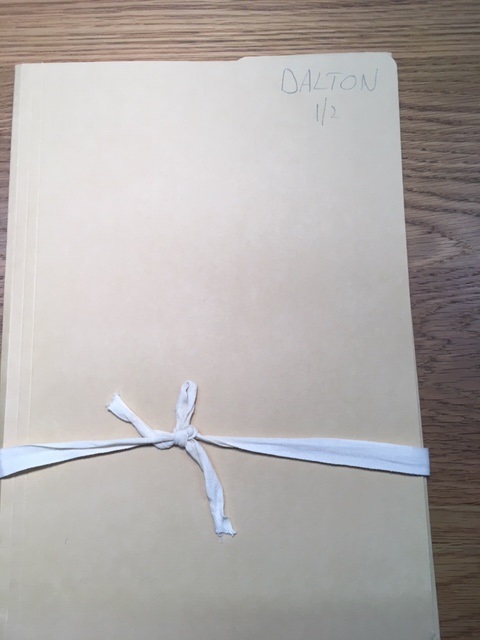

When you request a document from the LSE archives, it is put into a small glass locker to which you get a key to. Stacked neatly are the sources you request, in a smooth brown envelope with neatly tied rope. Opening it literally feels like unlocking history. Perhaps one that wasn’t intended for me. Reading the diaries, I wondered what could be concluded about Hugh Dalton? What could be gathered from the past that can be applied to the present? And what could be drawn from the life and archives of a man who could not be further from the person reading his books and papers? Here is what I jotted down in-between carefully thumbing through dust-scented papers.

Notes on an archive

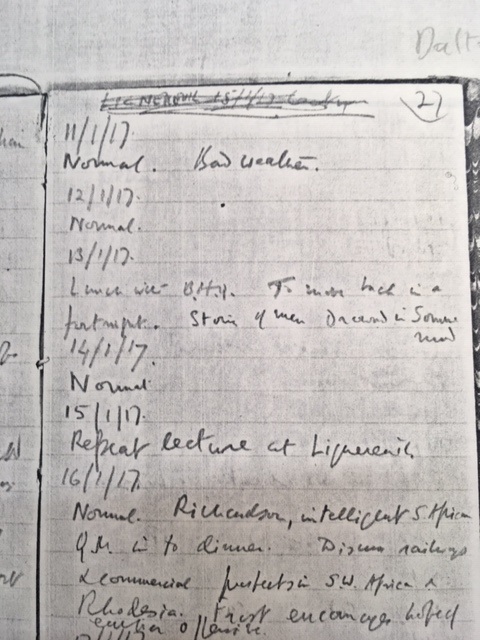

Dalton/1/1 first source: illegible handwriting. Closer to hieroglyphics than anything else. Thank u, next. Jan-Oct 1916. I wish there was Word Doc in 1916 – that would help. I think a lot of all the histories we lose, letters that never reached the intended readers, grandparents dying before sharing their experiences with us, illegible handwriting containing different angles. And if they existed – what would it change?

Dalton 1/2/: second source

Surprise, surprise the handwriting is still atrocious. What can we tell from people’s writing? Is it significant – like a horoscope, favourite TV show or food? In this I can only understand the line from 24/10/16 which reads “called at 6 am. No time for any breakfast. Train crawls to Staples, where we change at 9 o’clock.” Even if it’s not earth-shattering, ground-breaking, I’m here holding it. More than a hundred years of history. And all I can think to do is complain, how Gen Z of me.

The diary entries from 12/11/16 read: Normal.

Was there a normal day in the war? This is a new concept, one of war as a see-saw; what is someone’s worst day is another person’s normal day.

18/11/16: Normal.

19/11/16: Normal.

11/1/17: Normal. Bad weather.

12/1/17: Normal.

14/1/17: Normal.

Making up with the past

Dalton refers to London, to LSE. I think of this often as a History student. The places I occupy and the history they have. Unspoken but present. Shadows of the past lingering unknown only to those who happen to know. What would he make of me? If anything? Does it matter?

What was most pertinent to me about Dalton’s archives was the immensity of the mundane and what to make of that. It is understandable for us as historians to place ourselves within time capsules. Almost expected for us to imagine what those who bear resemblances to us would face in their lives in the bygone periods we study. Perhaps, it is even our duty; to unearth those forgotten pasts and not displace the mainstream but add to it. Signs of the particular historical narrative of the First World War followed me everywhere, glued to the floor of the 341 bus back home, radio shows, clickbait articles and special exhibits at museums and galleries. Comparing Dalton’s account of war to what I imagine people who looked like me, experienced, resulted in a harsh discordance. One I wanted to explore further.

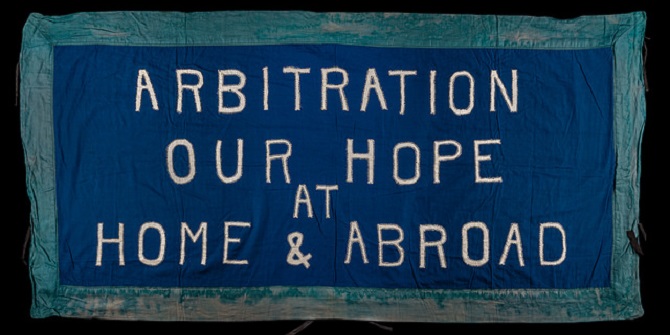

This is what led me to the Imperial War Museum (IWM): an exhibit on the lives of African soldiers. A gateway to quashing that incessant nag: how do I make up with a history that chooses amnesia over multiplicity? The outside of the IWM was draped in an installation of dripping red poppies. Two assistants stood by the entrance handing out interactive cards which asked: “What does the installation look like? What does it remind you of?”

I wrote: “the narrative/lens we write from will always haunt us. How do we view WWI in constructivist terms? In relation to British identity it was valiant, noble, the sweeping scene of a mass graveyard also commanding unwavering resilience. But what for the disenfranchised who fought too? A demonstration of a dynamic where men were forced to fight in a war only to be called back home where civic (dis)order was rooted in illegitimacy.”

Choices make up the fabric of the quotidian. How we react to each other, ourselves or the past is all a choice. Attending the 120 minute-long, triptych video installation by John Akomfrah at the IWM offered me a choice. The haunting images of brown and black bodies lowered into earth, a tan-coloured desert wasteland, a river of submerged objects: paraffin lamps, photographs, empty pails and a scene of an empty beach, hollowed out from the tide offered me something. The choice of a historical reckoning, shades away from judgement, even less shades away from complete rejection of the past. Rather than opt for the binning of histories that we are dissatisfied with, we should aim for the historical discipline to be one of multiplicities, celebrating courage and bravery as much as we acknowledge dispossession.

Marrying these two, Hugh Dalton’s overwhelmingly “normal” account of the War, noble accounts of the significance of the War to the British conscience and the exhibition on an interpretation on the lives of African soldiers, marred by silence forced me to choose. As a historian, as a student of colour, as a member of a drawn-up nation-state on a round table in 1885: I choose a history with more than one narrative. If I am allowed to choose what I hold on to from Dalton’s life, I choose his erudite theory on welfare distribution. This is the Pigou-Dalton Principle, which states that a social welfare function should prioritise the transmission of utility from the rich to the poor as long as this exchange does not result in the reversal of these status of the two. An application of this in the context of mainstream narratives could be handy in the historical discipline.

Read more

Dalton, H (1920), The Measurement of the Inequality of Incomes The Economic Journal, 30 (119), 348–361.

Hugh Dalton on the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Since this post was published, Hugh Dalton’s diaries covering 1916 – 1960 have been digitised and are available on LSE Library’s digital library https://lse-atom.arkivum.net/uklse-dl1hd01

Posts about LSE Library explore the history of the Library, our archives and special collections.