50 years ago in 1969 the School was closed for 25 days. LSE Archivist, Sue Donnelly, investigates the events and causes of that turbulent time.

By January 1969 debate within the School was focussed on three particular areas:

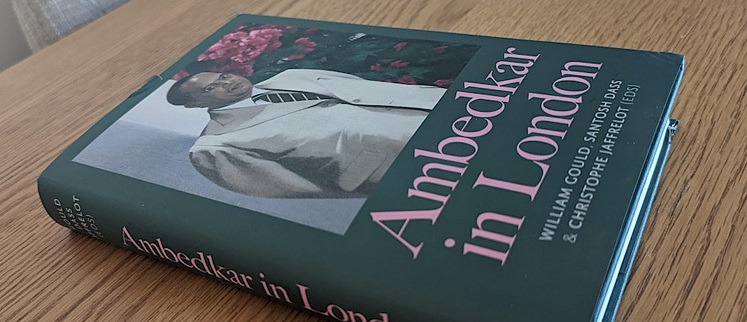

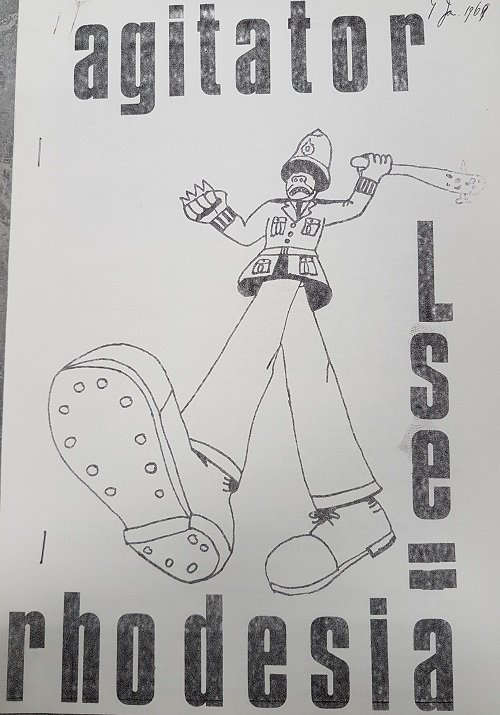

Firstly in January the Commonwealth Prime Ministers Conference was held in London and led to a resurgence of interest in the issue of possible links between LSE and its governors and investment in both Rhodesia and South Africa. The Agitator printed a pamphlet – LSE: Rhodesia, and both LSESU and the Socialist Society held meetings to discuss these issues. LSE Director Walter Adams attending one meeting was faced with demands to publish a list of LSE’s holdings in Rhodesia and South Africa, that all LSE governors should resign from the boards of companies trading with white southern Africa and that such companies should not be allowed to recruit on the School premises. Adams argued that the pamphlet was inaccurate.

Secondly the General Purposes Committee of Academic Board published a report which gave advice on dealing with disruption to lectures and examinations by students. Controversially it placed a responsibility upon staff to identify any students behaving obstructively and recognised that in exceptional circumstances “the use of force” might be justified. The report appears to have exacerbated the growing atmosphere of distrust.

Thirdly at a Union meeting attended by Lord Robbins at which the Socialist Society presented hostile questions on involvement in South Africa and the question of the gates (pictured below) – which Robbins admitted were intended to prevent “unauthorised access” – the SU passed an emergency motion that the gates be removed and as the Director later wrote the gates “suddenly became symbols of anti-student oppression”. On 22 January Academic Board adopted a series of resolutions condemning the unauthorised occupation of the School’s premises.

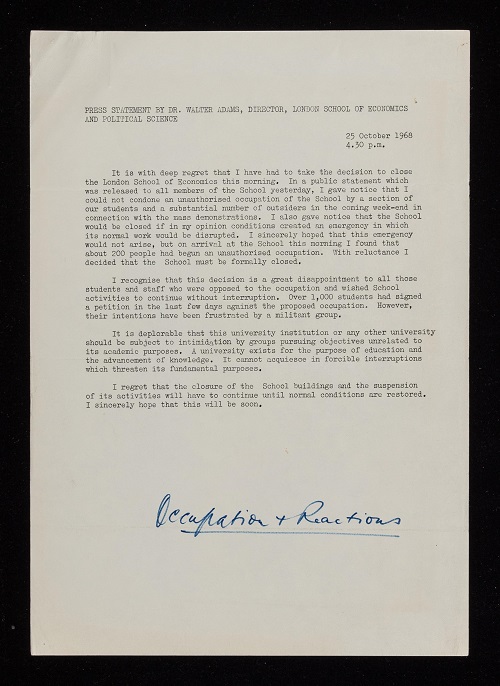

On 23 and 24 January the SU voted on a number of motions about the removal of the gates and finally voted 282 to 231 with 68 abstentions to tear down the gates. The motions were overseen by Meghnad Desai who was honorary President of the SU. Some students stormed out of the meeting to immediately begin dismantling the gates only to find senior academics in position to defend them. There was great confusion and at 9.30pm the Director declared the School indefinitely closed and as students left the building staff were given the distasteful task of identifying the “culprits”. Over 30 students were arrested and spent the night in the cells at Bow Street. The School took out injunctions against 13 students, four of whom were not from LSE, preventing them from entering the School.

The School was closed for 25 days and spread around Bloomsbury. The Students’ Union was based at the University of London Union Building and Academic Board and the School’s administration was based at Senate House. Some tutors managed to hold lectures and classes across London in their homes, cafes or other university buildings. In a speech in Parliament the Secretary of State for Education, Ted Short, described the activists as “the thugs of the academic world”.

The School was advised not to start disciplinary action while injunctions were in place on students, so attention turned to academics who were viewed as supporting the students. On 29 January Lord Robbins served notice on Robin Blackburn (Sociology), Nicholas Bateson (Social Psychology) and Laurence Harris (Economics) to appear before a special committee on 31 January and 1 February.

Standing Committee announced on 12 February that the School would re-open – but also warned that further action would lead to the re-closure of the School and notifications to grant awarding bodies, potentially depriving students of their grants. John Griffith, Ralph Miliband and J H Westergaard opposed the statement including “its limitation on the freedom of students to protest non-violently”.

On 18 February the SU responded with a statement of its views on the purposes of the School:

The LSE Students’ Union does not accept the strictly legal view that the London School of Economics is a ‘business’ owned and operated by the Standing Committee of the Court of Governors, under regulations laid down by them, and by them alone, Unlike the Plaintiffs, we do not regard the LSE as piece of property only. On the contrary, we regard the London School of Economics as consisting, in its most essential aspect, of its staff and students, working together for the purposes of their own choosing, rather than those imposed upon them by the LSE Court of Governors.

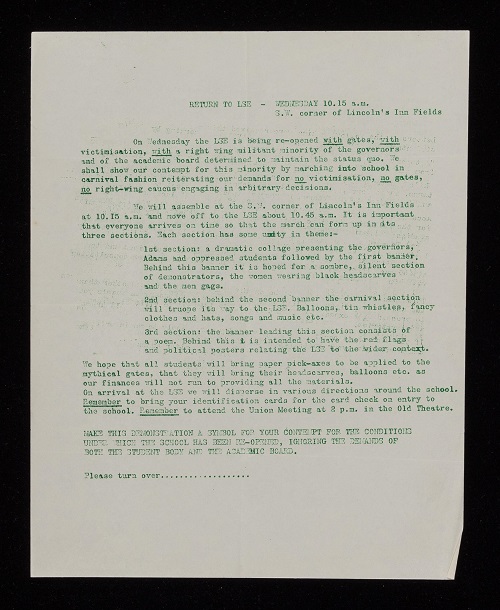

The School re-opened on 19 February. 300 students gathered in Lincoln’s Inn Fields to march to the School – but the SU meeting rejected an occupation motion and a token sit-in collapsed with lack of support.

But the rest of the year was marked by continued disciplinary hearings, sit-ins and the continuation of legal processes. By the end of 1969 Robin Blackburn and Nicholas Bateson had their contract terminated for misconduct and their dismissal was upheld on appeal. Laurence Harris was found guilty of misconduct but this was not deemed serious enough to warrant dismissal. In the High Court four students had been found guilty of trespass and damage and three were suspended from the School. Two foreign students were deported.

But in his annual Director’s Report Walter Adams tried to sound a note of optimism:

I am, however, confident that a later and impartial judgement will discover that in spite of all the tensions of the year the School emerged more united and clearer about it purposes and character.

It was true that in the coming years, although there were some tensions, there were no major disruptions to the work of the School. Walter Adams remained as Director until 1974 when Ralf Dahrendorf was appointed. Much later in his history of the School Dahrendorf commented that in the end it is important that both sides of the 1969 debate accepted the principle that the School was worth saving.

Read the rest of the series in The LSE Troubles

Visit LSE 1969, 18 February-15 March, a free exhibition in the Atrium Gallery.