Originally posted on the History News Network, this excerpt from Gregg Mitman‘s recent book discusses George Brown’s journey to Liberia, via the USA and LSE. He was an American doctoral student at LSE in the 1930s and, part of a cohort of anthropology students of African descent, a contemporary of Jomo Kenyatta and Eslanda Robeson.

Flying over the Liberian rubber plantations of Firestone Tire and Rubber Company in 1936, doctoral student George Brown did not see an exultant scene of transformation and development ushered in by American capital, industrial agriculture, and wage labour. He saw “an undesirable monopoly over the most valuable industrial territory in the country.” He saw “here and there” an “African village completely surrounded by the rubber forests.” He saw communities adapting indigenous economies “to meet living conditions in a forest no longer ripe with palms, coffee, cocoa, wild game, bamboo, cotton, woods for canoes and herbs for ceremonial and medicinal purposes.” He saw “low wage employment” driving “young people” to the city or the plantation. In short, he saw violence wrought by the extraction of land and labour by a Western economic system alien to the “spirit, philosophy, and benefits” that, he argued, animated the economies and “communal labours” of Liberia’s indigenous peoples.

Intellectual curiosity and structural racism shaped Brown’s peripatetic life. Brown was born in 1900 in Missouri but grew up in Kentucky where his family moved after his father, a Methodist pastor, narrowly escaped lynching for defending his wife from the taunts and sexual advances of a group of white men. When Brown was 16, his family moved again, to Cleveland, once an important stop on the Underground Railroad. When he was 17, the young man set off for Howard University in Washington, DC. There he became an understudy to Carter Woodson, who founded the Journal of Negro History in 1916. No one influenced Brown’s early intellectual life more than Woodson. Brown absorbed his mentor’s passion for using historical social science tools to document, record, and interpret the past and present experiences of Black people across the African diaspora. Like Woodson, Brown used those findings to combat scientific racism and white oppression.

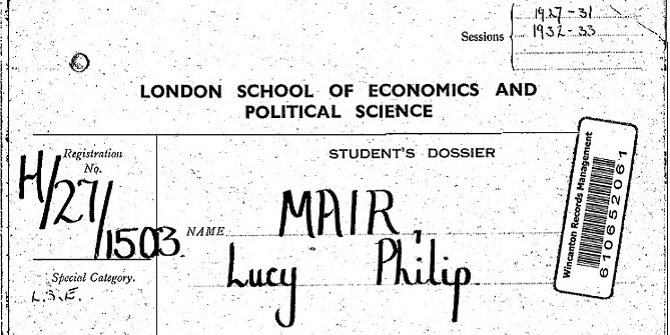

Brown’s journey to Liberia and to a political awakening to imperial aggression and racial oppression operating through the global economy came by way of London, not America. In 1934 he enrolled in a PhD program at the London School of Economics (LSE), taking graduate courses in anthropology, economics, and history. In the 1930s, London became a vibrant centre of Black internationalism and anticolonial thought. Brown attended gatherings of the League of Coloured Peoples, founded in London in the early 1930s by Jamaican physician Harold Moody to promote unity and welfare among all people of African descent. There he met renowned Black intellectuals, activists, and performers who were united in opposing the racial order of capitalism and empire: men like Jomo Kenyatta, who would help lead his country to independence from British colonial rule and become Kenya’s first president, and Trinidadian historian C L R James, then formulating ground-breaking work on the Haitian revolution and the history of Black resistance movements. In this intellectual ferment, Brown renewed his close friendship with singer and actor Paul Robeson and his wife Eslanda, both of whom shared his commitment to labour rights and socialist causes.

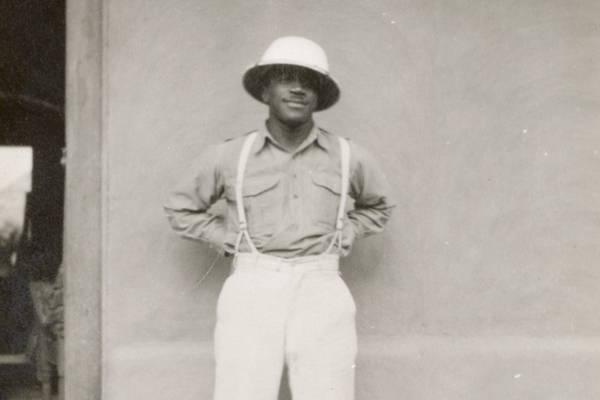

At the London School of Economics, Brown interacted with an international cadre of African, Afro-Caribbean, and African American graduate students. They shared experiences and ideas and challenged and confronted the colonial perspectives and institutions of their white professors. The tools of anthropology, economics, and history—used to buttress empire and white supremacy—were taken up by students of African descent and, as LSE anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski said, turned into “weapons against us.” In the autumn of 1935, as Italian troops invaded Ethiopia, sparking anti-imperial and anti-racist critiques among Black intellectuals, Brown left for Liberia. Liberia was, thanks to the savvy diplomacy of its President Edwin Barclay, the one country on the African continent that had not fallen to Western imperial conquest. Writing from his position as head of history and political science at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, future Nigerian president Nnamdi Azikiwe looked to Liberia in 1934 as “the nucleus of a black hegemony,” where the “hope of an African civilisation” emphasizing African ideals “of hospitality, of friendliness, of honesty, of truth, of justice, and of the brotherhood of man” might be realised. Brown, armed with a Kodak camera, steeped in anthropology and history, energised by anti-colonial and socialist struggles, and supported by Paul and Eslanda Robeson, travelled to Liberia in search of not Western but African values and ideals.

Brown’s interest in the exchange relations of indigenous economies took him to Liberia. He sought to understand the different economies at work on the Firestone concession, then the “largest single rubber development in the world,” within Liberia’s settler society, and among Liberia’s rural indigenous population. Among the Gola and Vai people in the Liberia’s Western District, the American stranger was welcomed. Brown observed, even then, the reach and influence of the embryonic Firestone plantations, roughly two-hundred miles south. When someone from a remote village asked for permission to build a hut, the local chief asked, “Which stranger are you? Rubber stranger or cotton tree stranger?” The question was meant to elicit whether the stranger was someone “who ‘come soon, goes soon,’ like rubber” or who would, as symbolised by the sacred cotton tree, put down roots and become part of the community.

Brown keenly observed the activities of life in Liberia’s hinterland. He wanted to understand how different forms of exchange—of land, of goods, of labour—structured social interactions and meanings within and among communities. He followed the movement of rice with intense scrutiny: harvested from fields by women, carried to town by boys and men, stowed in the village storehouse by women and boys, and divided into shares among chiefs, elders, “witch doctors” and “medicine men.” In Voinjama, a major trading hub in Liberia’s northwestern corner, Brown observed market day in detail and the intricacies of bartering and trade. In Bendaja, near where the Mano River marks the Liberia–Sierra Leone border, he noted the elements and rhythms of the rice harvest festival.

Through his interactions among the Vai and Gola peoples, Brown came to understand the central place of land in the meanings, values, and social relations that shaped rural Liberian communal life. Brown sought to document a communal set of relationships among people, non-human others, and land that fostered ways of being and values not readily subsumed by industrial capitalism. These were not “primitive” economies, he argued, but were cooperative industrial systems. They depended upon a set of exchange relations that upheld the community rather than the individual and informed the collectivist nature of social and spiritual life in Africa.

At the base of such indigenous economies was land, Brown argued. Land, and its communal uses, dominated and structured the rhythms of life in the village, the farm, and the forest. Together, Brown observed, village, farm, and forest formed “an African social trinity,” each part of which was integral to and played an important function in the “social order of indigenous Africa.” Brown left Liberia enamoured with the communal values and lifeways of his hosts, values which stood in contrast to the individualism of American culture and the capitalistic economic system upon which it thrived.

This essay is an excerpt from Empire of Rubber: Firestone’s Scramble for Land and Power in Liberia (The New Press) by Gregg Mitman. It has been reproduced here with permission from the History News Network.

Browse more LSE History Blog posts from the Anthropology collection