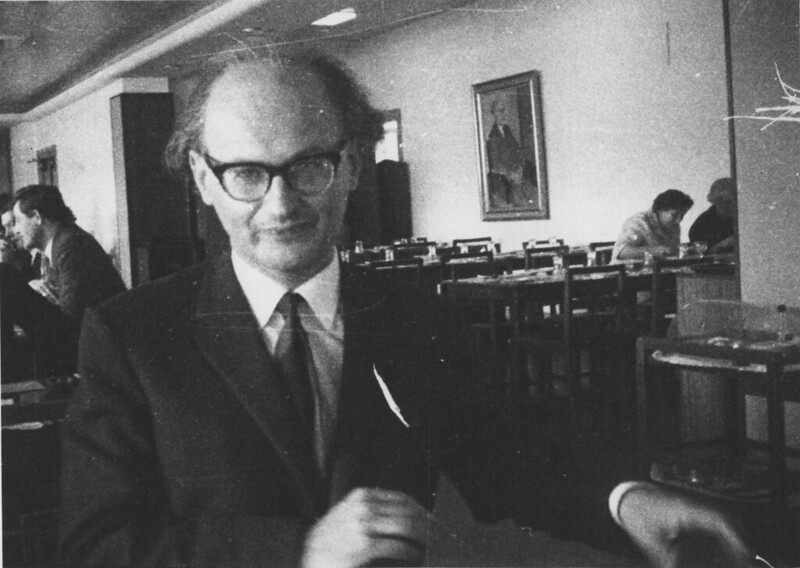

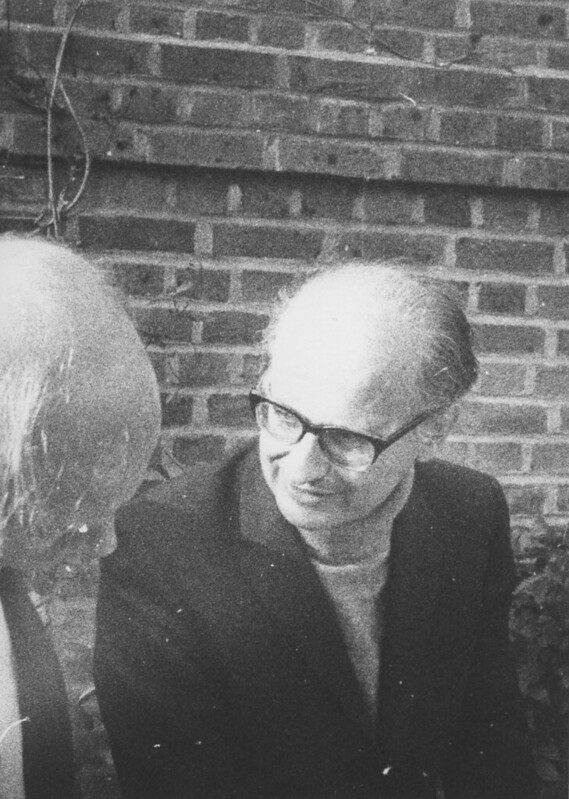

John Worrall introduces Imre Lakatos (1922-74) who taught philosophy at LSE from 1960. Today the department’s home is in a building named after him.

You may have wondered why LSE has a Lakatos Building. That building, which houses the Department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method, was in fact donated to the School by Spiro Latsis – a former PhD student of Imre Lakatos’s – with the request that it be named in his teacher’s memory.

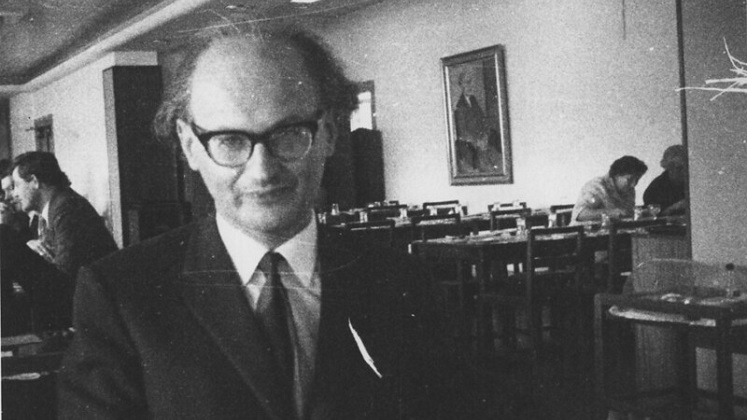

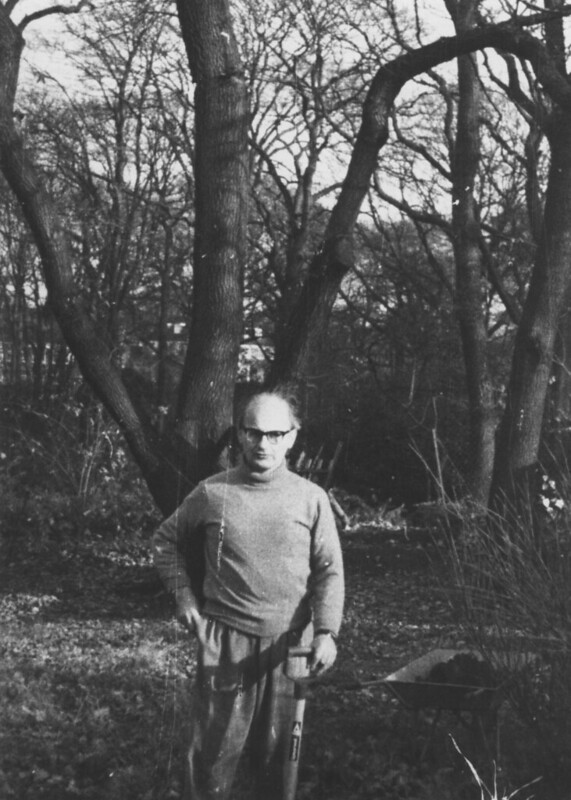

Lakatos, the centenary of whose birth was celebrated via a major international conference held at LSE in November 2022, worked at the School from 1960 until his untimely death in 1974. During his time at the LSE, he did ground-breaking research in both the philosophy of mathematics and the philosophy of science – work which continues to be highly influential worldwide.

Lakatos was born “Imre (Avrum) Lipsitz” in 1922 in Debrecen, Hungary. He left Hungary in 1956 shortly after the Hungarian Uprising having earlier, during the German occupation, changed his name away from the clearly Jewish “Lipsitz” to “Imre Molnar” and then, during Communist times, to a more working class-sounding surname (“Lakatos” means “locksmith”).

The story of his Hungarian years is shrouded in controversy. For many in intellectual Budapest Lakatos was and is an almost satanic figure – organiser of an “enforced suicide” of a fellow Jew at the time of the Nazi occupation; and, during the post-war Communist period, a driving force behind deeply-resented Stalinist education “reforms” and a regular Secret Police informant on his friends. Lakatos was certainly involved in all these things, though the issue of moral culpability at a time of almost inconceivable tension and upheaval is a disputed grey area. Except, that is, in the case of the last charge where I think Lakatos was fairly plainly innocent: he once told me that in post-war Budapest, everyone was informing on everyone else. “The smart people made sure that they only told the Secret Police (AVH) what they already knew.” Chief amongst those informed on by Lakatos was the distinguished historian of mathematics, Arpad Sƶabo. Although Sƶabo later became fully aware of what Lakatos had done, the two remained close friends – Szabo staying at Lakatos’s Hampstead home on a number of visits to London. This surely confirms the idea that Lakatos’s “informing” had little or no deleterious effect.

Whatever the truth about his Hungarian activities, Lakatos certainly did not leave the country without emotional scars of his own: his mother and maternal grandmother (who raised him) were both murdered in Auschwitz and he himself spent three years, from 1950 to 1953 is Recsk, the worst of the Hungarian Stalinist prison camps. (Most of the time, he was kept in solitary confinement.) And certainly, the Imre that some of us feel privileged to have known in London, although undeniably a force of nature with very strongly held views, seemed miles away from anything “Satanic”.

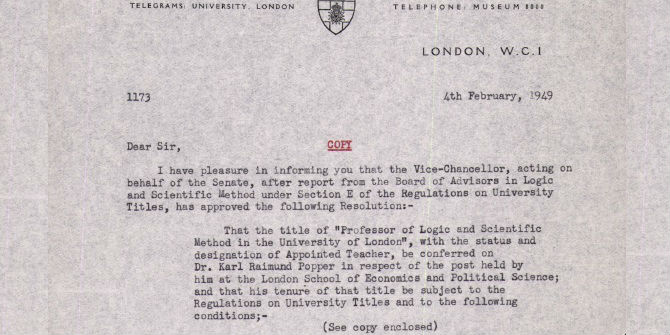

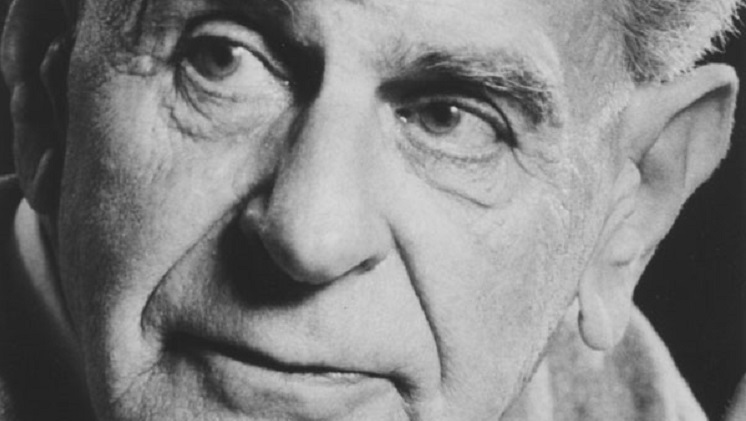

Lakatos came to the UK on a Rockefeller Foundation scholarship and enrolled at Cambridge for a (second) PhD under the supervision of the mathematician and philosopher, Richard Braithwaite. Although Lakatos was largely inspired by his compatriot Gyorgy Polya and Braithwaite seems to have played a mostly formal role. Lakatos had read some of Karl Popper’s work while employed at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (including, surprisingly, The Open Society and its Enemies) and made a point of immediately introducing himself to Popper and quickly becoming a regular attender at his Seminar at LSE. Lakatos later described himself as having “fallen into the magnetic field of [Popper’s] intellect”.

Rightly or wrongly, he viewed his work in the philosophy of mathematics (his Proofs and Refutations based on his second PhD) as extending Popper’s fallibilist philosophy into the unlikely area of (informal) mathematics. And Lakatos’s main contribution to the philosophy of science – his methodology of scientific research programmes – is a major revision of Popper’s approach based on a view of falsifiability and falsification that is in much closer touch with the actual history of science.

Having created an enormous impression through his contributions to the Popper Seminar and through widely read drafts of parts of his Proofs and Refutations, Lakatos was appointed to a Lectureship at LSE in 1960, rapidly rising to become full Professor (in “Logic, with special reference to the Philosophy of Mathematics”) in 1969. Following Popper’s retirement in 1968, Lakatos became the main driving force within the Department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method and behind its continued major international reputation. His lectures, always delivered in the evenings (he believed the day should be reserved exclusively for extending the boundaries of philosophy), became famous within the School and were widely attended by students and staff outside of Philosophy – for example, by Ernest Gellner, the distinguished sociologist/social anthropologist, who recorded:

“He lectured on a difficult, abstract subject riddled with technicalities, the philosophy and history of mathematics and science; but he did so in a way which made it intelligible, fascinating, dramatic and above all conspicuously amusing even for non-specialists. When he lectured, the room would be crowded, the atmosphere electric, and from time to time there would be a gale of laughter.”

You can hear recordings of a couple of his lectures at this Lakatos memorial page, though, in my opinion, the recordings sadly found him in far from top form. Audio versions of some of the talks given at Lakatos @100 held in LSE in November 2022 are available to catch up on.

As well as the Building, Lakatos’s name lives on in the LSE via the Lakatos Award – the major international research prize in philosophy of science awarded annually and administered from the Department of Philosophy and Scientific Method.

Despite the brevity of his career – he died aged 51 having held an academic position for less than 13 years, Lakatos not only built a major international reputation on the basis of his work, but also inspired and guided a surprisingly large number of PhD students (myself included).