Author Barbara Ingham introduces her biography of Ida Greaves (1907-1990). A doctoral student at LSE in the 1930s, Greaves hailed from Barbados. Her pioneering work on colonial monetary systems in the 1950s was highly controversial and she became one of the “missing female voices” whose contributions have been overlooked or undervalued.

This biography, the first for Ida Greaves, is one in which both the personal and intellectual narratives are patchy. There are twists and turns, gaps and dead ends, and many unanswered questions. But as it stands it is a story worth telling. It is an attempt to reconstruct a career and a particular era, before the past wholly disappears. Its subject is Caribbean economist Ida Cecil Greaves.

I never met Ida Greaves. She is known to me only through her remarkable books, articles and reports, plus a series of letters held in the LSE archives, which she exchanged in the 1940s with the distinguished LSE professor, Arnold Plant.

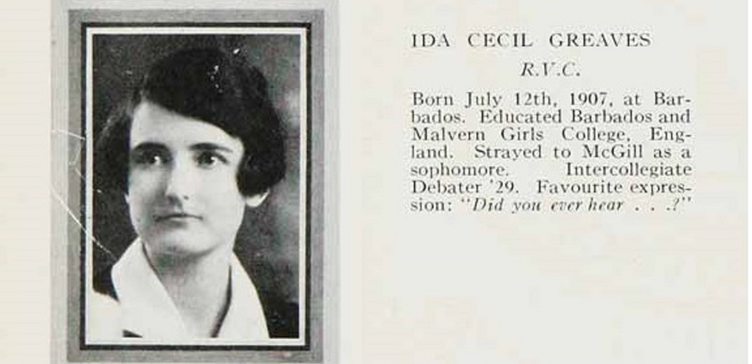

Briefly, she was born in Barbados, in St Michael parish, in 1907 and spent five years at boarding school in England followed by undergraduate and postgraduate studies at McGill in Canada. She was a doctoral student at LSE in the 1930s, and after a spell teaching in the US she returned to London in 1943 to take up a research and advisory appointment in the Colonial Office. This was followed by a temporary lectureship at LSE in the newly emerging discipline of development economics.

Unfortunately there is only a very limited amount of personal information on Ida Greaves on which to build a biography. Even Barbadian academics currently compiling a dictionary of distinguished islanders have been hard pressed to provide much in the way of family information on Ida Greaves. It is apparent that she travelled extensively between the 1920s and the 1950s, by sea of course, travelling to the United States, to South America, to West Africa, the Caribbean, and back to London. She researched and taught in the United States, and worked in the United Nations, connecting with distinguished figures of the day. But the detail is lacking. Ida Greaves did not co-author books or papers, and it has been difficult to identify colleagues who might have known or worked with her. Intellectual biographies have a valuable place in the history of ideas, but if they are not underpinned by a personal narrative sadly they do a disservice to their subject. This is especially the case for those like Ida Greaves, one of the many “missing female voices” whose contributions have been overlooked or undervalued by academics.

My own interest in Ida Greaves’ work dates from the 1990s, when I was researching the history of the colonial monetary systems. Ida Greaves, (who had died in London in 1990 at the age of 83), had prepared reports on the colonial monetary system for the Colonial Office in London in the 1940s. Her carefully researched work on colonial monetary systems was becoming better known in the 1990s. It was beginning to attract interest and praise from academics researching currency boards. In the 1950s however, her reports and other publications on colonial monetary systems were highly controversial. In the run–up to decolonisation critics on the right regarded her approach as dangerously “anti-colonial”. On the left she was readily dismissed as an apologist for colonial exploitation. Strikingly, all her earlier writings which dated from the 1930s, on race and class, on poverty and employment in developing countries, were largely ignored by academics. Yet it is pioneering work of high quality, with surprising resonance for the modern day reader.

The years she spent at Royal Victoria College, (the women’s college at McGill), were to have a huge influence on the path she trod in her later career. The Department of Economics and Political Science at McGill in which she studied both as an undergraduate and as a masters student was chaired at the time by Professor Stephen Leacock, a complex character better known today as a best-selling humorist writer of the 1930s and 1940s. But he was also a serious economist, and significantly a theorist of the American institutionalist school who had studied at Chicago under Thorstein Veblen.

Ida Greaves in her subsequent writings as a development economist was to follow closely her teachers at McGill, focusing less on the immutable laws of the market, and more on human motivations under the influence of changing social, political and legal histories.

After McGill Ida Greaves held research and teaching fellowships at prestigious Radcliffe and Bryn Mawr Colleges in the United States, but neither institution seemed to offer what she was seeking. In 1932 she applied from Bryn Mawr for admission to the London School of Economics. She was accepted as a PhD (Econ) student under the supervision of Professor Arnold Plant. In London in the early 1930s she connected socially with many the leading feminist activists who had been brought together by Margaret Haig Thomas (Lady Rhondda) and the Six Point Group.

But her academic work was not neglected and the doctoral thesis she produced was described as brilliant by her examiners. On the recommendation of Arnold Plant it was published by Allen & Unwin in 1935 under the title Modern Production among Backward Peoples. In more recent years (1968) it has been reprinted as an economics classic. It is a much neglected but remarkable pioneer study in the discipline of development economics, focusing on labour supply in plantations and peasant smallholdings in tropical areas, under a variety of social, political and legal influences.

Also registered at LSE in 1933, though in his case on the undergraduate programme, was another student from the Caribbean. This was Arthur Lewis, a black student who arrived at LSE in September 1933 from St Lucia, a neighbouring island to Barbados in the East Caribbean. Arthur Lewis was eventually to receive universal recognition as development economist, a Nobel Prize-winner in economics. There is no evidence that Arthur Lewis met Ida Greaves at LSE during his undergraduate degree studies between 1933 and 1936 but both were fortunate in having had Arnold Plant as their doctoral supervisor, and both were to serve as colleagues on the Colonial Economic Advisory Committee (CEAC) in London during World War II.

When CEAC was disbanded in 1945, Ida Greaves returned to Barbados to live at the home of her father. Her lively and outspoken letters to Arnold Plant in London date from this period, and contain shrewd, critical accounts of the management of the economy of Barbados in the latter days of colonial rule. In 1948, following her secondment to the United Nations, she returned to London when she was offered a temporary teaching post at LSE.

The vacancy at LSE had come about indirectly through Arthur Lewis and his promotion to a Chair at University of Manchester. Though Lewis had taken on a wide range of teaching at LSE during the war years, including lecturing on prestigious courses in the core economics programme, he lost this teaching when senior colleagues returned from wartime service. He was effectively downgraded and asked to lecture on a one year vocational course provided by the University of London for graduate cadets in the colonial service. It was not the rigorous economics course that Lewis would have expected and its low intellectual status was probably a major influence on Lewis, when he decided instead to take up an appointment of a Chair at Manchester.

His proposed departure left LSE with a problem. Who was to provide the teaching required on the vocational course at such short notice? Alexander Carr-Saunders the LSE Director wrote to Ida Greaves asking for her help on the Colonial Economics course. She responded positively to the request and returned to London. Though invited to continue teaching beyond 1948 it was only to be on a “temporary” basis year on year, and she declined the offer. She was never offered a permanent post. The post vacated by Lewis as Reader in colonial economics was never filled.

It was during her time at LSE that Ida Greaves began her research into the colonial monetary system. It had been her long-standing ambition to introduce a monetary dimension into studies of underdevelopment. Money and Banking had been her chosen post-graduate specialism at Radcliffe College (Harvard). She believed that it was a highly significant though much neglected feature of colonialism. Funding for the research and associated fieldwork in West Africa came from the Colonial Office. The outcome was her controversial Report on Colonial Monetary Systems published by HMSO in 1953.

In 1950 Ida Greaves left London to take up a post in Trinidad. In the following years she spent time in the West Indies, and in universities in the United States and in Britain. Throughout the 1950s she had an impressive publication record in leading journals with articles on currency systems, on trade and payments, central banking in developing countries, and on labour in plantation economies. The output was evidently of high quality, since it included contributions to the Journal of Political Economy, the Economic Journal and the American Economic Review. But it is not easy to set these publications in context and by the 1960s her academic career was effectively coming to an end.

Ida Greaves: a pioneer development economist by Barbara Ingham is published by Routledge.