This Women’s History Month, we are shining a light on the history of women’s work by delving into our Women’s Library archives, writes Mhairi Gowans. The Women’s Library at LSE is the oldest and largest library in Britain devoted to the history of women’s campaigning and activism. By using our archival resources, we aim to uncover what life was like for working women in a series of different jobs – starting with the 19th century coal mining industry.

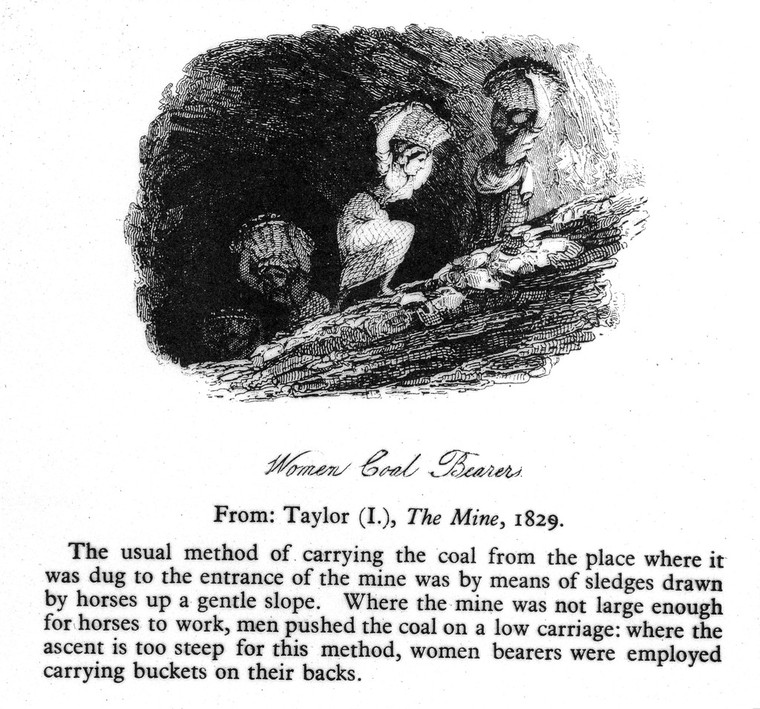

For our first post, we are exploring the history of bearers – women workers who bore coal from the pit to the surface, a role which was predominant in Scotland during the Industrial Revolution. The quality of life of these women was examined by Richard Bald, a Scottish civil engineer, who wrote a report on women workers in the Scottish coal industry. In his inquiry, Bald describes the daily life of the women who were employed as bearers. From leaving their babies in the care of elderly female neighbours, descending the pit with their older daughters, to returning to a cold home at the end of the day, the women had a challenging existence.

The height ascended by them, when loaded, is equal to more than four times that of Arthur’s Seat above the level of the sea.

– An Inquiry into the Condition of the Women who Carry Coals Underground in Scotland, Robert Bald

The weight a woman would carry in a day was in the region of 4,080 lbs (291 stone), according to Robert Bald’s calculations, but the wages she would receive for such a day’s work was only eight pence (to put in context, a loaf of bread was about 16p). Unmarried women not working in a family group became known as “fremit bearers” and could be easily mistreated by the male collier employing them. As Bald describes, the collier could force his fremit bearer to carry loads heavy enough to “break not only the spirit, but the back of any human being.”

From this view of the work performed by bearers in Scotland, some faint idea may be formed of the slavery and severity of the toil, particularly when it is considered that they are entered to this work when seven years of age, and frequently continue till they are upwards of fifty or even sixty years old.

– An Inquiry into the Condition of the Women who Carry Coals Underground in Scotland, Robert Bald

Women were expected to work through pregnancy, which also meant that miscarriage and infant death were common. Isabel Wilson, 38, testified to a government investigation into mine work that she had had 10 children in 19 years of marriage and experienced five miscarriages due to the strain of carrying coal while pregnant.

I have always been obliged to work below till forced to go home to bear the bairn, and so have all the other women. We return as soon as able, never linger than 10 or 12 days many less, if they are much needed. It is only horse-work, and ruins the women; it crushes their haunches, bends their ankles and makes them old women at 40.

– Isabel Wilson, Children’s Employment Commission, 1842

The hope of labour reformers such as Robert Bald was that by freeing women and children from the pits, coal mining families would experience an improvement in living conditions. Having all the family members employed in the pit meant that there was no time for domestic work, which was a full time job in this period before labour saving devices. Bald hoped that women being at home would therefore improve the quality and cleanliness of home life.

Eventually in 1842 the Mines and Collieries Bill was passed by Parliament. This banned underground work for women and girls as well as boys under ten. However, many women still needed to earn a wage and consequently women took work on the pit surface instead. Nonetheless, the act benefitted children who were now able to go to school and stopped women from doing more physically dangerous work in the pits. However, the Act today is viewed with mixed opinion as there is also an argument that it may have resulted in forcing women into lower paid and less structured forms of employment.

Do we not all acknowledge the very high and extensive influence of women in society? Do we not pay them a ready tribute? Let the condition of this class of women be bettered, and most undoubtedly the best consequences will follow.

– An Inquiry into the Condition of the Women who Carry Coals Underground in Scotland, Robert Bald

Robert Bald’s full report into the condition of female coal miners is available to read at the LSE Digital Library.

An interesting piece.Thanks.

I was aware of the slavery and destitution that was the ‘Black Hole’ of the births and deaths in Scottish mining; from attempting to navigate around it during investigations into my family tree [Midlothian 1649 until Berwick 1798]; and have see words attributed to those that bear my name, in extracts from the report by R F Franks to the Children’s Employment Commission on the East of Scotland 1842; as well as the conditions of those 11, 14, and 18 year olds ….

It surprises me that somehow my line survived!