In this essay Arushi Vats reviews ‘Dalit: A Quest for Dignity’, published in 2018 by the Nepal Picture Library. The work is a unique collection of photographs that seek to capture the lives of the Dalit populace, an ostracised minority, over six decades in Nepal. Vats analyses the interaction between readers, photographers and the subjects of the compendium, musing on the reverberations of power hierarchies in photo-archives.

From a treatise dating back to 1854 on purity and social organisation, to the abundance of caste elites in contemporary leadership positions in state and civil society, the history of Nepal is illustrative of how caste-based dominance can mutate and thrive in diverse political arrangements, over vast tracts of history. Caste as a system of social segmentation, economic deprivation and exclusion, political desubjectivation, and material expropriation touches every aspect of life in Nepal.

In the heirarchical order of caste, Dalits are groups which are subordinate to higher castes such as Bahuns (Brahmans), Chhetris and Thakuris (Kshatriyas) among others, but also the middle and “impure” caste groups. Across Hill and Tarai regions, Dalits are groups which rank the lowest in caste heirarchy. This heirarchy has implications for their identity and lived experience. Joel Lee, an anthropologist studying caste and religion in South Asia, writes that the caste system is based on the “ideological premise that every caste has its own distinctive, hierarchically ranked ‘place’ in the world, and that the places inhabited by subordinate castes should not only be set apart but should look, smell, and feel differently from those of the rest of society.”1 The function of caste is thus, enforcing and sustaining a discriminatory system of status that manifests through the mechanisms of untouchability, marginalisation, and exploitation—a reality which is captured in the poor health, literacy, and financial outcomes among communities oppressed by caste-based dominance.2

The questions concerning “caste” in Nepal are invariably questions of access to polity and economy, language and land, the past and the future. An enquiry into the continuing prevalance of caste as a principle undergirding formal and informal institutions, relationality and recognition, is a probe into the determinative force caste exerts by denying emancipatory futures and an effort to see the fractures that have been appearing in the foundations of these structures through sustained challenges to its legitimacy.

In a piercing introduction that dwells on the discomforts of understanding “documentary photography” as performing a representational function or as an unmediated repository of social truth, Divas Raja Kc writes of the imperative to “remain alert to the miscellany of Dalit identity while also acknowledging the pull of Dalit unity.”3 Dalit: A Quest for Dignity, published in 2018 by photo.circle a platform established in 2007 to promote critical photographic practices and enquiries in Nepal, contends with a collection of images produced by predominantly non-Dalit photographers. In foregrounding concerns with how and by whom these images may have been produced, their circuits of mobility, and the modes of disattenuated subjectivity they could permit the viewer—Dalit is a project in critiquing power hierarchies within photo archives. It is, simultaneously, an effort to transform the radical potency of such archives through interventions that help in “expanding the horizons,” of each image. In exploring the possibility of reading images anew—as witness to voices that may otherwise be elided, the photo book transforms these into critical tools in exploring the “inconclusive histories that emerge from the past, erased from the institutional narratives […]” The photo book asserts that even as images contain and are cast in a given context, their futures remain undetermined. Photo archives are thus, simultaneously, sites of excavating the past and building alternative futures.4

The endeavour of being cognisant of but not constrained by the authorship of the photograph reflects theorist and filmmaker Ariella Azoulay’s assertion in Civil Contract of Photography, that a photograph “exceeds any presumption of ownership or monopoly and any attempt at being exhaustive.”5 Azoulay calls for a shift from the paradigm of a descriptive “seeing” to an alert “watching” of photographs. Watching, for Azoulay, “entails dimensions of time and movement that need to be reinscribed in the interpretation of the still photographic image.”6 Tina M. Campt, theorist of visual culture and contemporary art, argues for another sensorial mode—“listening,” which precludes attention to frequencies, reverberations and inaudible sounds that radiate from a photograph. “Listening” to photographs requires the accentuating of voices and stories of the people who are present in the frame and those who aren’t, attending to details that don’t register on the surface; it also requires an exploration of practices that are invisible or “quiet,” working as “fugitive” histories within the image.7 In many ways, Dalit is an exercise in “watching” and “listening” to photographs, observing and interpreting the histories that precede, seep into, and exceed the singular photographic moment; understanding photographs as a “space for political relations.”

Prior to assuming the form of a photo book, many of the images featured in Dalit were displayed as an exhibition in Patan Museum by the Nepal Picture Library in 2016, and at the 14th edition of Angkor Photo Festival in 2018. The book recognises this journey, noting that the mode of confrontation and contemplation enabled by both these formats of encountering photographs are distinct. In its part, the photo book traces the historic arc of the past century of modern Nepal, and is divided into three sections, with a duo-lingual stream of text running concurrently in English and Nepali. The first section, titled “Toilers of the Land,” presents a selection of images that help understand the imbrication of caste within the Nepalese economy. One of the initial images in this section belongs to Tuomo Manninen’s Kathmandu series (1995), which featured social groups of various kinds, from Stock Exchange employees to school scouts, organised in a formation and looking directly at the camera. This image depicts women from the Chyame community standing outside a municipality office in Lazimpat. The Chyame are among the most ostracised groups, placed lowest in the hierarchy of castes. In this image, the women confront the lens with a defiant assurity, holding broomsticks, and in one case, an infant. Even as the technique of gazing directly at the camera is common to the series—other groups that are a part of the Kathmandu series such as formal labourers and school children are attuned to being photographed together, in arrangements that convey fraternity and belonging. In the instance of the image of Chyame women, this act of posing gains symbolic valence as a moment of “transgression” where the subject of the photograph reclaims the representational space offered to them.

The sequence of images in this section depicts Dalit persons at their places of work—which are often in proximity to or part of their homes, accompanied by equipment—broomsticks, sewing machines, tools of scourging and farming. The subjects in nearly every image gaze directly into the lens, a counterposition to the system of caste, which operates on notions of purity and pollution, and is premised fundamentally on the “denial of the Dalit face,”and the distancing of the Dalit body. Diwas Raja Kc notes that the practice of denial and distancing emanates from the Hindu notion of “darshan,” which Christopher Pinney argues is foremost a state of mutual recognition “of seeing and being seen by a deity,” and additionally, an event of “emboldening” of senses and selfhood.8 To be considered polluted, then, is to be denied of a personhood. This section illustrates how such practices of discrimination shape economic structures—images depict the plight of Badis, whose segregation toward prostitution has only intensified; others shed light on the assignage of waste and activities such as the skinning and disposal of animal carcasses to vulnerable castes. In these sequences of images, the reader is made to realise the sensorial properties of caste; one can sense the “stench” of rotting carcasses as a woman covers her nose with her hands. The olfactory, in many ways, is a caste-specific dimension of the “listening” and “watching” of photographs; as scholars Gopal Guru and Joel Lee among others have noted, “smell” is an integral part of the caste system.

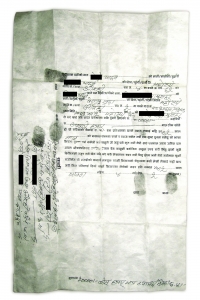

While the persistence of such methods of discrimination is evidence of institutional failure to address caste-based inequities, Dalit highlights para-institutional means of subjugation which compound the creation of an economy of caste. A fragile facsimile of a letter of borrowing shows mechanics of entrapment as the figure borrowed is not entered in the accorded field, but rather scribbled at the bottom of the letter, to be struck in case the borrower is unable to repay, while a much higher amount is entered above. Such techniques of intimidation and duplicity are intrinsic to the sustenance of an indebted and indentured group of labourers, and in perpetuating the extent of deprivation endured by Dalits. The instance of economic participation is then, one of “adverse inclusion,” a concept that has been applied to understand the appropriation of indigenous resources and land, and extended to understand predatory and expropriative economic practices that impact vulnerable sections.

The second section, titled “The Sound of the People,” offers a rich visual anthropology of traditions of public music and folk forms, highlighting the centrality of Dalit performers to the shaping of lok geet, or nationalist music. A central task that the book undertakes is the remaking of epistemologies of economy and culture, such that forms of labour and performance that rely on analogue tools and manual practices are regarded as not inferior or “backward,” but as critical parts of contemporary economy. The book is suspicious of the redemptive promises of modernity, arguing that it brings with it an order that renders invisible and “shameful” modes of labour that it nevertheless requires for sustenance. This section showcases how resistance and movement is tied deeply to performance traditions within Dalit communities of Nepal. The charge of the “public” that animates Dalit musical traditions, also runs through its activism. Images of performing troupes smoothly make way for temple entry activists. An image tells the tale of Hira Parki, who despite playing the drum outside Shaileshwari temple from a young age, had never been permitted entry. Despite activists securing his entry to the temple, Parki was terrified, eventually losing consciousness upon entering the temple. The resounding vibrations in the pictures of dolakhi, damaha, and pankhebaja, transition to images that come alive with rallying cries and slogans for social justice—presenting the confluence of two distinct, yet corollary auditory planes through interpellated images.

Two photographic arrangements are sonorously stark: the first is a grid of selfies of Ajit Mijar, who was murdered in an instance of “honour killing” in 2016 for eloping with his Brahmin girlfriend. The second is a grid comprising the repetition of an image of a tree, a spot where a Dalit girl was raped and murdered. These images belong to the Jagaran Media Center, an NGO established by by journalists representing Dalit and marginalised communities. Both these grids subvert the prevalence of visual seriality as a tool for governmentality, used in instances of identification and homogenisation. Tina M. Campt notes that this genre of identification photography, realised through “documents of suspicion” such as passports and identity cards, was “created to validate and verify identity as a uniform set of multiples intended to produce an aggregate image of a group of individuals.”9 In replicating the visual form of identification photography, but presenting the images of Mijar, which are self-created, and a landscape which bears witness to a crime, Dalit practices a “fugitivity,” infusing disquiet into the frame.

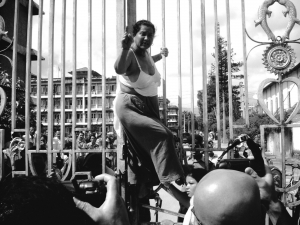

In the final section, titled “Artisans of Freedom,” the photo book circles back to its opening and most recognised image—T R Bishwakarma’s addressing the modification of Muluki Ain in 1963. Muluki Ain a written common code formulated in 1854, instituted many forms of discrimination, including caste-based differentiation and untouchability drawing from the Hindu faith. This section is replete with images of leaders who shaped the pro-democracy movement, including archival images of B R Ambedkar’s visit to Nepal, and celebrations of Muluki Ain Divas and Bhim Jayanti. Images in this section display Dalit leaders at work “organising, educating, agitating.” Particularly fascinating are studio images of leaders such as Bishwakarma, holding books—an agentic visual vocabulary that signalled the break of upper-caste monopoly over education and literacy. A remarkable set of images, arranged as snapshots in the Introduction, feature the “petticoat protest” of Uma Devi Badi, a human rights activist who advocated vociferously for the rights of the Badi community. In 2007, after prolonged peaceful protests failed to gain response, Uma Devi Badi removed her top at the entry gate of the government—symbolic of the prostitution imposed on Badi women. The series of images featuring in Dalit depict Badi as she climbs the gate, her back revealed to us, and arms of possibly members of the police pull her down. It’s a dynamic moment, suspended mid-motion, conveying as Parki’s story did, the body as a bearer of both trauma and disestablishmentarian might.

Images of Uma Devi Badi’s “petticoat protest,” Kathmandu, 2007, Jagaran Media Center. Courtesy Nepal Picture Library.

In setting out to perform an “accounting of humiliated history,” Dalit creates a framework for understanding radicality in still images, steadily revealing and constructing relations between diverse and conjoined narratives of being Dalit in Nepal. The concluding images of the volume present scenes of protests from the recent past, a multitude of protesting bodies and banners as they march, address, sing, and perform in the public—exceeding the edges of each frame. The decision to close the photo book with the invocations of continuing mobilisation and organising, and the reflexive nature of these struggles that cast a luminous glow on freedoms in the making, remind us of Audre Lorde’s dictum: “Revolution is not a one-time event. It is becoming always vigilant for the smallest opportunity to make a genuine change in established, outgrown responses […]”10

Arushi Vats is a writer based in New Delhi. Her interests include art, politics, and ecology. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Critical Collective, Write | Art | Connect, Scroll, Quint, and Mint.

Note: All images have been published with the kind permission of the Nepal Picture Library and have been given due credit.

Endnotes

1 Joel Lee, “Odor and Order: How Caste Is Inscribed in Space and Sensoria,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 37 No. 3 (December 2017), 470.

2 Unequal Citizes: Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal, Department for International Development, http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/201971468061735968/pdf/379660Nepal0GSEA0Summary0Report01PUBLIC1.pdf.

3 Diwas Raja Kc, “Introduction,” Dalit: A Quest for Dignity (New Delhi: photo.circle, 2018), 14.

4 Ana Catarina Pinho, “Albums of a Dictatorship: Photography archive, memory and counter narratives,” photographies 13:1 (2020): 113-136. Accessed on 21 August 2020.

5 Ariella Azoulay, “Introduction,” The Civil Contract of Photography (New York: Zone Books, 2008), 12.

6 Ibid., 14.

7 Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2017).

8 Christopher Pinney, “Introduction,” Photos of the Gods: The Printed Image and Political Struggle in India (Londn: Reaktion Books, 2004), 9.

9 Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images, 22.

10 Audre Lorde, “Learning from the 60s,” Black Past, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/1982-audre-lorde-learning-60s/#:~:text=Revolution%20is%20not%20a%20one,each%20other’s%20difference%20with%20respect.