In this article Jordan Buchanan examines the decline in British trading paramountcy in Argentina between 1914 and 1929 and explores the diplomatic efforts made by Britain to protect its economic interests. He draws parallels between British-Argentinian negotiations in 1929 and the current trade negotiations being undertaken by the British government in the wake of Brexit and argues that Britain can either repeat or learn from its mistakes.

‘Wake up, England!’ was the demand of the British Ambassador in Argentina during his galvanising speech at the Chamber of Commerce meeting in Buenos Aires, March 1927.[1] Ambassador Malcolm Robertson was reacting to his country’s declining influence in Argentina’s economic affairs. Between 1914-29, global events and international competition weakened Britain’s trading paramountcy in the Argentine Republic. Recovering Britain’s pre-1914 leadership was an exacting task for the country’s traders and diplomats. Much like the current challenges for British trade diplomacy while the country discusses post-Brexit trade deals, in the 1920s, Britain applied concentrated diplomatic efforts to protect its economic interests.

Argentina was a vital economic ally for Britain between 1870-1914. The republic optimised its agricultural production for exporting its produce to the industrialised nations in the North Atlantic – especially to Britain.[2] Argentina took advantage of the rising consumer demand for agricultural products in Britain as the British labour force migrated to the cities and devoted their hours to the manufacturing industry.[3] The trading network between the two countries served Britain’s economic interests as Argentina became an important agricultural supplier and a market for British industrial goods such as textiles, and iron and steel products. However, the outbreak of World War One (WWI) initiated a divergence in the Anglo-Argentine connection from its prior trajectory.

Between 1914-18, Britain recalibrated its economic activity in response to the wartime demands. The Argentine connection dropped down on the priority list for British political and economic actors as they directed their focus to winning the war.[4] Distracted and limited by the war in Europe, Britain’s trading position in Argentina dwindled.[5] This scarcity of British activity in Argentina presented an opportunity to the U.S. traders who had been working resolutely to establish themselves as the main importer of industrial goods since the beginning of the twentieth century.[6] Foreign Affairs highlighted that the U.S.A. ‘exploited the wartime conditions’ to export its products while ‘Argentina took whatever it could’ in the absence of European trade.[7] Therefore, Argentina had adjusted its import practice to fulfil its requirements from elsewhere, allowing for the rise of the U.S.A.’s trade influence.

Despite British diplomats’ equanimity regarding the emergence of the U.S.A. as the largest importer to Argentina, British actors could not recover their country’s pre-war supremacy in the republic. In 1919, The Economist claimed that ‘British goods continue to hold an absolutely unchallenged reputation for quality in this [Argentine import] market… the ground lost during the war will no doubt be recovered in time.’[8] Nevertheless, U.S. traders’ dynamism constrained Britain’s post-war recovery in the Argentine import market. In 1922, the president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in Argentina emphasised how the changing Argentine attitude towards U.S. goods was contributing to the success of U.S. commerce. He highlighted that ‘there is no negative prejudice against American goods or manufactures in Argentina’ and that ‘the previous animosity of Argentine businessmen towards American businessman has disappeared.’[9] British traders were no longer able to depend on favouritism in Argentina as consumers’ distrust of U.S. products evaporated. From 1919-1926, British traders competed for the lead import position, but they were unable to permanently overtake the U.S.A.[10]

Similar to how British trade representatives were hoping for a return to pre-1914 trade conditions after the war, modern Britain is hoping for auspicious conditions after its return as an autonomous trading nation in 2021. After 1914, the USA supplanted Britain’s trade paramountcy in Argentina, and in the twenty-first century the former now competes for world trade dominance with China.[11] Is the modern world order a favourable environment for British traders? Like The Economist myopically forecasted in 1919 about post-war trade, is Britain overly optimistic about being an important international trader in the twenty-first century? Owing to the changing trade dynamics in Argentina after 1914, British traders’ expectation to recover their paramountcy in Argentina was negligent. The outcome of this careless behaviour is an important lesson for modern British trade diplomats as they discuss new trade deals with countries that already meet their import and export necessities; diligence is necessary.

Failing to recover its pre-war distinction, Britain’s link in Argentina had become fragile. In early 1927, the British Ambassador Malcolm Robertson complained that ‘it was almost humiliating’ that Britain ‘was being driven out of the [Argentine] market by the United States.’[12] According to Robertson, Britain had to reinsert itself into the economic leadership role it previously boasted in Argentina. Diplomatic communication from 1927 illuminates the extent of the British apprehension over its position in Argentina: ‘the question of British trade in the Argentine is of great importance to the people of that country, just as it is to ourselves.’[13] The country’s declining status worried the British diplomats due to the importance of the Argentine market. Consequently, commercial and diplomatic representatives initiated a new trade campaign.

“Buy from Those Who Buy from Us” was a British campaign to encourage Argentina to import more British products; reflecting Britain’s high-volume purchase of Argentina’s agricultural goods. Britain and Argentina hoped to benefit from establishing a pattern of reciprocal trade that maintained a balanced international trade account. However, Britain gained the least out of this trade strategy. British total value of imports into Argentina remained stagnant, whereas the total value of U.S. imports into Argentina continued to rise.[14] The new trade campaign did not change Argentina’s import practice or consumer behaviour. Argentine consumers had already become accustomed to their flashy U.S.-produced radios and motorcars such as Chrysler and Dodge motors; British linen was decades out-of-fashion. Thus, the “Buy from Those Who Buy from Us” campaign was a flop.

Consumer behaviour in 2020 remains a major influence during the current age of liberal capitalism; the consumer determines the demand curve. Britain is about to become an independent trader in a global economy in which countries have already developed consumer patterns and trade deals to reflect these features. After WWI, the hubris and negligence of the British community in Argentina weakened its ability to regain its trade paramountcy. Therefore, British arrogance regarding an ability to recover its pre-1973 trade position after 2021 would be to replicate the errors of the 1920s. Today, if Britain were to ignore the changes to consumption while it negotiated fresh trade deals, the country would achieve almost nothing for its economy.

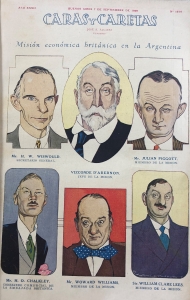

In September 1929, British diplomats began a secondary effort to recuperate Britain’s trade position; deploying the D’Abernon Mission.[15] Reflecting on the trading circumstances in Argentina, Viscount D’Abernon, reported that ‘the average Argentine household thinks now in terms of [American-made] motors, gramophones and radio sets than of [British-made] Irish linens, Sheffield Cutlery and English china and glass.’[16] Argentines wanted to purchase U.S. goods, not the out-of-fashion British products. The mission’s representatives offered Argentina favourable trade credit to promote the purchase of British products.[17] Nevertheless, as the trade envoy was concluding the deal with the Argentines, Wall Street was crashing; the ramifications rendered the D’Abernon agreement obsolete and Britain remained commercially stagnant.

Members of the D’Abernon Mission. Author has permission to use image from Caras y Caretas.

Members of the D’Abernon Mission. Author has permission to use image from Caras y Caretas.

For modern-day Britain, global changes remain pertinent to the country’s twenty-first-century activity. Similar to the Anglo-Argentine connection’s historical bookends (the U.S.A.’s rise after 1914 and the Wall Street Crash in 1929), the emergence of global China and the economic uncertainty of COVID-19 are global chapters in Britain’s new diplomatic history. For Britain, the task of being a major global trader is as elusive now as it was after 1914. Multiple global traders have conducted long-term national strategies to dominate the world economy; Britain’s nascent loneliness on the world platform means it will have to contend in the 2020s with vigorous competition like that of the 1920s.[19] Moreover, as countries close their borders and protect their own economies from the ominous Coronavirus, Britain is attempting to assert itself in a period of economic uncertainty similar to that after the Wall Street Crash.

To conclude, the global events from 1914-29 weakened Britain’s trading power in Argentina. Neglecting the shifting global power dynamics, the British community in Argentina ingenuously assumed that they would easily retake their top trading spot from the U.S.A. in the 1920s. Despite British protagonists’ eventual reaction, they could not regenerate Britain’s trade paramountcy. In 2020, simultaneous with vast changes to the global economy, Britain negotiates new trade deals for after leaving the E.U. The country’s current trade ambassadors have the potential to repeat or learn from Britain’s mistakes in Argentina between 1914-29.

Jordan Buchanan is a recent graduate from the MPhil in World History at the University of Cambridge where he researched the consequences of the Panama Canal in Argentina. Currently, he is working on an oral history project that focuses on the emergence of specialty coffee in Mexico.

Featured image: Clock tower gifted by the British to Argentina in 1910. Photo taken by the author.

[1] “Wake Up, England!” Buenos Aires Herald, 5 March 1927.

[2] Rubinzal

[3] Elena, Eduardo. “Commodities and Consumption in “Golden Age Argentina.” Online publication in Oxford Research Encyclopaedia: https://oxfordre.com/latinamericanhistory.

[4] O’Rourke, Kevin. & Findlay, Robert. Power and Plenty: Trade, War and the World Economy in the Second Millennium. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009) p. 431-435

[5] Thorp, Rosemary. “Latin America and the International Economy from the First World War to the World Depression.” In: Bethell, Leslie (Editor). The Cambridge History of Latin America. Volume IV: c. 1870 to 1930. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986) p. 57.

[6] Gravil, Roger. “Anglo-US Trade Rivalry in Argentina and the D’Abernon Mission of 1929.” In: Rock, David. Argentina in the Twentieth Century. (London: Duckworth, 1975). p. 42-43.

[7] H.H. Hipwell. “Trade Rivalries in Argentina.” Foreign Affairs, October 1929.

[8] “Argentina.” The Economist, 29 November 1919.

[9] “The Outlook for American Business in Argentina.” The Review of the River Plate, 24 February 1922.

[10] Revista de Economía Argentina, 1930.

[11] Bruno Maçães. The Dawn of Eurasia: On the Trail of the New World Order. (London: Penguin Books, 2019).

[12] “British Trade in Argentina.” Buenos Aires Herald, 2 March 1927.

[13] Emphasis added by author. The U.K. National Archives. FO371/11957. “General Correspondence, 1927.” Memorandum, 04/01/1927.

[14] Derived from: Mitchell, B. R. International Historical Statistics: The Americas, 1750-1988. (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1993). p. 435 & 471.

[15] Gravil. “Anglo-US Trade Rivalry in Argentina and the D’Abernon Mission of 1929.” p. 41-65.

[16] Rock, David. The British in Argentina: Commerce, Settlers & Power, 1800-2000. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019) p. 267.

[17] “La Argentina y Gran Bretaña abrense reciprocamente un credito de $100.000.000.” La Nación, 10 September 1929.

[19] See: Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2017). Maçães. The Dawn of Eurasia.