When Frank Robinson died in 2004, he was among the most famous buskers in Britain. Poems eulogised him, obituaries flooded with tributes, and memorial campaigns began in his honour.[1] Years later, Robinson continues to inspire acts of public remembrance.[2] It will probably surprise many, then, that this legacy is owed to a distinct absence of ability. One historian opines that his act was “remarkable for his lack of musical talent as he plinked and plonked on his trusty toy metallophone.”[3] Another accuses Robinson of “bashing his instrument tunelessly”; The Times simply called him “hopeless”.[4]

Born in the Nottingham suburb of Cotgrave around 1932, little else is known about the so-called “Xylophone Man” before he appeared on the city’s Lister Gate in the late 1980s.[5] Such obscurity makes Robinson’s a historically peculiar life, if only peculiar for its ordinariness. Most knowledge of it is lost, destined for oblivion by what Thompson terms “the enormous condescension of posterity”.[6]

But the ordinary should not be condescended. As Hobsbawm writes, “collectively, if not as individuals, such men and women are historical actors. What they do and think, makes a difference. It can and has changed culture and the shape of history”.[7] That Robinson’s daily audience numbered in its thousands hints at this potential.

In this piece, I describe his commemoration before situating its quiet radicalism within an international and theoretical context. I then draw on the influence of Don Quixote after its English publication in the early eighteenth-century to explain how and why the public came to remember the eccentric Robinson in the first place. Discussing the social conformity that underpinned this remembrance, I argue that views of his character as being at odds with modern capitalism have parallels in the Renaissance and represent his most authentic historical impact.

Remembering the Ordinary

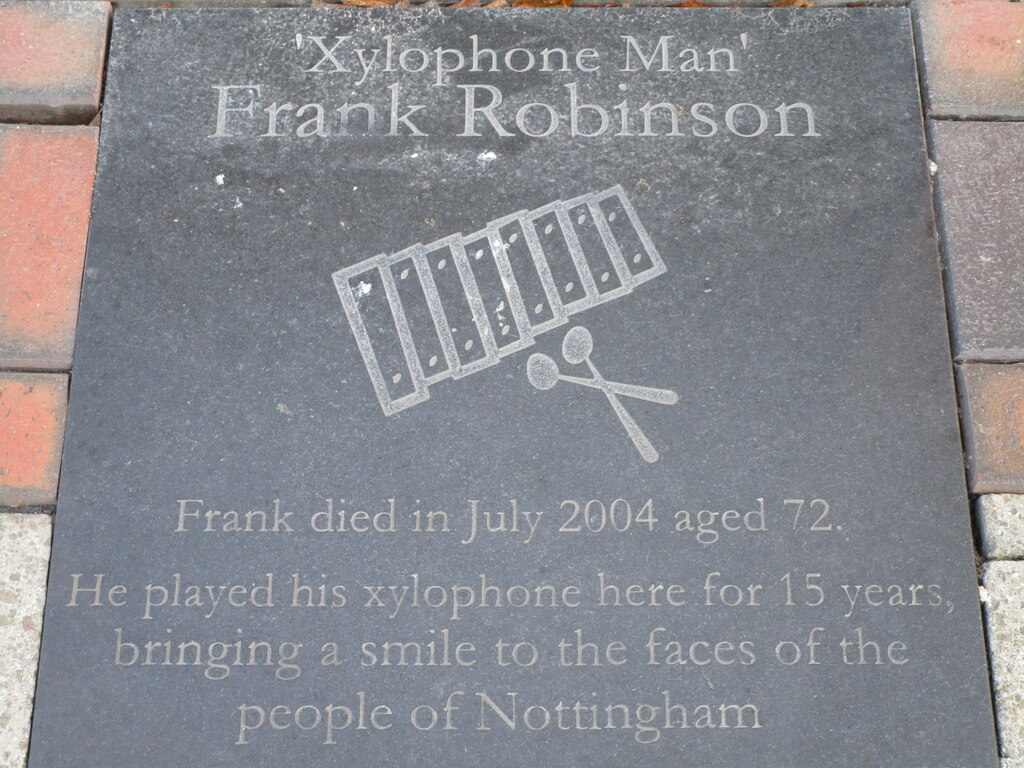

Robinson is an antithesis to the notion that public memory only respects great men of high politics.[8] In 2005, campaigners convinced Nottingham City Council to unveil a marker to him on the pitch he once busked. It reads: “He played his xylophone here for 15 years, bringing a smile to the faces of the people of Nottingham”.[9] A tribute band revisited the granite slab in 2014, and, four years later, Historic England publicised the memorial as one of several to celebrate “the often inspirational and poignant stories they tell.”[10]

Commemorating the ordinary is as global as it is radical. Spraycan tributes adorn the walls of neighbourhoods in New York, recalling loved ones killed by drugs, poverty, and police.[11] In Cairo, the murals’ subversiveness is more direct, reclaiming public space from authority while paying homage to the martyrs of the revolution of January 2011.[12]

According to Lefebvre, it is precisely this type of communal display–organic and “bottom-up” in its nature–that allows an urban area to be understood.[13] Official monuments, although easy to access and comprehend, must be seen as “deceptive fragments” used by the powerful to conceal social and historical realities.[14] Fittingly in our case, this connects to Lefebvre’s conception of the city as a musical “score” longing to be performed.[15]

In places where there is political upheaval, the implications of public remembrance (and amnesia) can and have been revolutionary. Renan famously posits that nations are based equally on what is forgotten than what is remembered.[16] Times have been much stabler in Nottingham. Regardless, behind Robinson’s memorial lies the fact that “after more than a decade on the streets Xylophone man [was] instantly recognizable to a wide range of the public. More so than any local politician [or] member of the council”.[17]

Indulging the Eccentric

What made Robinson so unforgettable? Cervantes’ Don Quixote became widely popular in Britain when Peter Motteux published an English translation in 1700–1703. Released in a European culture increasingly hostile to madness, this version diluted Quijano’s eccentricity– “which had always been grasped as a form of minor madness”–to conform to early modern behavioural expectations.[18] He was to be dotty but admirable, silly but benevolent.[19] The hidalgo was mentally ill with a loving heart.[20]

Foucault views Don Quixote and characters like him as the beginning of Europe’s “amused indulgence” of the eccentric, a social tolerance predicated on the belief that such behaviour was at once harmless and ridiculous.[21] But where there is ridicule, there is often scorn. The following passage reveals the discreet prejudice Robinson faced before reverting to an expression of the amused indulgence that ultimately secured him a favourable reputation:

“… the rumours spread. He was a millionaire who had gone a bit mad. He was a musical extortionist who would target shops in town, banging away until the manager came out with a tenner. He was an undercover Fed. In short, he was suspected of being everything except the thing he actually was; a genial old chap bonging away on a metallophone and yelping along to himself with undisguised glee because, well … he wanted to.”[22]

Seeking the Truth

A more candid theme in descriptions of Robinson presented him as proof that there was an alternative to the anonymity, repetition, and unfriendliness of twenty-first-century capitalism. One onlooker wrote that he “punctuate[d] the greyness with evidence of lives lived otherwise”, while another remarked that “coming out of your rammel job … you’d see Xylo bashing away with a smile … and you’d wonder who the really mad people in town were.”[23]

Here we must be wary of mankind’s veneration of Dryden’s noble savage, supposedly wiser for his rejection of civilisation.[24] By contrast, Lizzie Mackenzie’s film The Hermit of Treig (2022) is a recent and persuasive portrait of a social outcast’s life in Britain as being paved with loneliness, physical decay, and a constant awareness of death.[25]

Nevertheless, the idea of an eccentric embodying some higher truth does have earlier roots in the Renaissance. Within theatrical performances of the period–such as during the Feast of Fools in Flanders and Northern Europe–it was the role of the “madman” to demonstrate the folly of the self-styled “reasonable”. To deceive humanity’s deception of itself by not conforming, as if hiding a great and unknowable secret.[26]

Foucault argues that this influence of the “unreasonable” coincided with the fall of Gothic symbolism, claiming that the latter’s “network of spiritual meanings … had begun to unravel”.[27] Similarly, if we, like others, view Robinson’s presence as incongruous with everyday capitalism, he too can be seen to have challenged the system in a small and indirect way. For example, mentioning Robinson, The Observer wrote that buskers offered an “element of surprise” that the modern music industry had failed to replicate.[28]

Conclusion

“I don’t pretend that I’m Mozart, I’m just having a bit of fun and keeping people entertained”, insisted Robinson in his only published interview.[29] This comment is enough to make any historian squirm. He did not intellectualise himself, nor did most people that witnessed him. To study his personal past and psychology, if at all worthwhile, would require inaccessible sources. However, as part of a broader tapestry, Robinson can help us to understand the perceptions of historically ordinary people from across the world: of built environments, of others’ behaviours, and of the social systems that framed their lives.

Robinson is a radical example of a regular public commemorating what it alone considers to be significant, taking this decision away from self-interested authorities. Conversely, the reason for this remembrance indicates a more conservative popular attitude. To many, Robinson was cherished because he was a ridiculous eccentric who, in the end, still observed their basic behavioural standards. A more genuine compliment of Robinson was that he disturbed the mundanity of Britain’s capitalist culture. Evoking the Renaissance, a period unburdened by Don Quixote’s affable template, it was Robinson’s subtle and subconscious otherness that struck the truest chord with his listeners.

[1] Rosie Garner, “Xylophone Man Poem”, LeftLion, 2004: https://archive.ph/6mG9y; “Xylophone man is dead”, BBC News, July 2004: https://archive.is/nHio; Jared Wilson, “Xylophone Man Tram Update”, LeftLion, 8 September 2004: https://archive.is/mMjJo

[2] Akhila Thomas and Rebecca Sherdley, “Lister Gate’s dramatic artistic makeover transforms gateway to city”, Nottingham Post, 7 August 2023: https://archive.ph/9Us8n

[3] Stuart Burch, “‘Reading the City’: Cultural Mapping as Pedagogic Inquiry” in Nancy Duxbury, W. F. Garrett-Petts and David MacLennan (eds.) Cultural Mapping as Cultural Inquiry (London: Routledge, 2015): p. 204.

[4] Joanne Lee, “Life can always be different…”, Eccentricity, no. 1b (2008): p. 4; “City honours Xylophone Man”, The Times, 16 November 2005: https://archive.ph/TQcTJ

[5] Paul Speed, “When top Nottingham busker Xylophone Man used to lift our spirits”, Nottingham Post, 23 April 2022: https://archive.ph/QrsP2

[6] E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (London: Victor Gollancz, 1963): p. 12.

[7] Eric Hobsbawm, Uncommon People: Resistance, Rebellion and Jazz (London: Abacus, 1999): p. viii.

[8] Burch, “‘Reading the City’”, p. 205.

[9] “City honours Xylophone Man”, The Times.

[10] The Frank Robinson Tribute Band, “A Tribute to Xylophone Man”, Visit Nottinghamshire, 2014: https://archive.ph/cqiV2; “Uncovering England’s Secret, Unknown or Forgotten Memorials”, Historic England, 2018: https://archive.ph/4usfn

[11] Martha Cooper and Joseph Sciorra, R.I.P.: New York Spraycan Memorials (London: Thames & Hudson, 1994).

[12] Kelly Leilani Main, “Bombing the Tomb: Memorial Portraiture and Street Art in Revolutionary Cairo”, Berkeley Undergraduate Journal 28, no.1 (2015): p. 160.

[13] Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (Donald Nicholson-Smith trans.) (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991 [1974]): p. 149.

[14] ibid., p. 96.

[15] ibid., p. 211.

[16] Ernest Renan, What Is a Nation? (Ethan Rundell trans.) (Paris: Presses-Pocket, 1992 [1882]): p. 3.

[17] Jared Wilson, “Xylophone Man 1931–2004”, LeftLion, 6 July 2004: https://archive.ph/FjKDf

[18] Brian Cowlishaw, A Genealogy of Eccentricity (unpublished PhD thesis) (University of Oklahoma, 1998): pp. 13–14.

[19] ibid., pp. 29–30.

[20] ibid., p. 14.

[21] Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (Richard Howard trans.) (London: Routledge, 2001 [1961]): p. 191.

[22] Al Needham, “King Bong: The Xylophone Man”, LeftLion, 4 July 2012: https://archive.ph/e9UWC

[23] Lee, “Life can always be different…”, p. 4; Needham, “King Bong”.

[24] John Dryden, The Conquest of Granada by the Spaniards (London: Henry Herringman, 1672): pp. 7–8; cf. Rousseau, Dickens etc.

[25] Lizzie Mackenzie (dir.) The Hermit of Treig (Cosmic Cat, 2022).

[26] Foucault, Madness and Civilization, p. 11.

[27] ibid., p. 15.

[28] “A perfect pitch”, The Observer, 15 August 2004: https://archive.ph/1C0q5

[29] Wilson, “Xylophone Man 1931–2004”.

Featured Image: Plaque to Xylophone Man – Frank Robinson; Copyright: El Loco and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.