Focusing on the major cases of genocide in twentieth-century Europe, including the Armenian genocide, the Holocaust and genocide in the former Yugoslavia, as well as mass killing in the Soviet Union, this book outlines the internal and external roots of genocide. Using the voices of the human actors in genocide, often ignored or forgotten, this volume aims to provide arresting new insights into the discussion of genocide in other continents and historical periods. Caroline Varin would have liked to see more content suitable for advanced readers and students, but would recommend this book to readers looking for a quick overview of the subject of genocides in Europe.

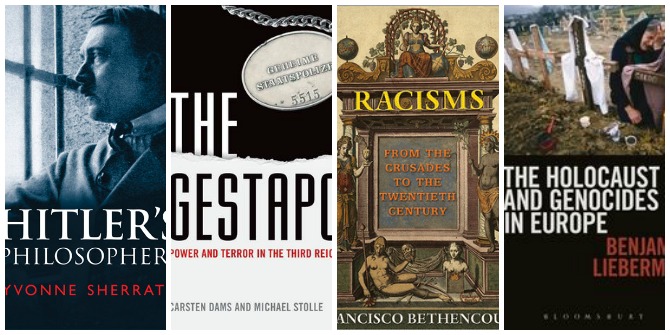

The Holocaust and Genocides in Europe. Benjamin Lieberman. Bloomsbury Academic. April 2013.

The Holocaust and Genocides in Europe. Benjamin Lieberman. Bloomsbury Academic. April 2013.

Europe in the twentieth century was arguably the most dangerous place in the world to be among the minority. The collapse of European empires, the emergence of national identity, and the wave of migrations across the continent all contributed to a growing hostility towards minority groups who could be easily identified and blamed for the ills of the nation. In The Holocaust and Genocides in Europe, Professor Benjamin Lieberman examines the causes that led to the targeted killing of entire groups of people who were perceived to be ethnically or religiously different.

The book presents four cases studies of genocide: the Armenian genocide, the Holocaust, ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia, and the killing of Kullaks in the Soviet Union. The book is fast-paced and easy to read, with study questions at the end of each chapter and suggestions for further reading. Although Lieberman develops several interesting ideas and the book appears factual – offering anecdotes and accounts from various sources – it is poorly referenced, which weakens the message of the author. Furthermore, it is difficult, if not impossible, to fully cover four European genocides in the space of one book. Lieberman’s narrative style makes assumptions about the reader’s previous knowledge on the subject, without really going into enough details to interest or be credible to a student of European history. I would recommend this book to readers who want a quick overview of the subject of genocides in Europe with the caveat that it is more descriptive than analytical.

Lieberman begins his study by examining the trends in European history that led to genocide across the continent in the space of just 80 years. Europe’s record of violence is anchored in its history of colonialism and imperialism, which led to the destruction of entire civilisations. This was justified through the politics of nationalism and the emergence of racial sciences. In several European countries, including the United Kingdom, governments infused these ideas into the population through the manipulation of the press and radio, enabling them to manipulate and influence popular sentiment.

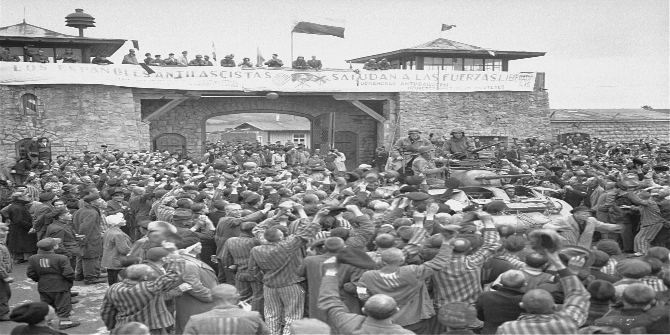

One of the most interesting ideas developed in this study is the role of bystanders. Although Lieberman argues that an inner core of perpetrators were responsible for carrying out genocide, a broader circle of perpetrators that includes bystanders and even victims enabled these events to take place. In Bosnia, for example, paramilitaries of ordinary citizens would come together during weekends to perpetrate their crimes; during the Holocaust, Jewish ‘U boats’ were encouraged to collaborate with the Nazis and search and denounce fellow Jews in hiding. Lieberman does an excellent job unveiling the myths that populations were not aware of the killings going on around them, and aptly demonstrates what he calls the ‘gray zone’, where ignorance and passivity of ordinary citizens turned into forms of compliance. Finally, Lieberman also shows that victims attempting to resist or escape genocide faced enormous challenges, not least the rejection by other nations who refused to offer sufficient assistance: Switzerland accepted approximately 30,000 Jews into the country, but it also turned away about the same number. In a famous episode in 1939, the United States refused entry to 900 Jews seeking refuge.

In the concluding chapter, Lieberman draws an interesting parallel between European genocides and genocides in other parts of the world. The author argues that most genocide takes place during times of war: anti-Jewish policies became increasingly deadly after 1942 when Germany invaded the Soviet Union; ethnic cleaning in Yugoslavia took place among the break-up of the nation and a secessionist war among its sub-groups; the Armenian genocide began during the First World War One in 1915; whereas the purging of the Kullaks in the Soviet Union did not take place exclusively during a war, it was facilitated by the conditions of two World Wars that framed and accelerated the government’s policy. This would suggest that the threat of genocide is increased in times of war. The inclusion of the Rwandan genocide in 1994, however, disproves this theory and instead underlines the importance of ideological trends such as radicalisation as the crucial factor in targeted group killings. Ideological pursuits of nationalism and ethnic purity, Lieberman argues, is facilitated during times of war, but is often rooted in the events of the past. This is evident in African genocides, where colonial politics set a trend of violence and inequality among local populations. Anti-Semitic sentiment, which has persisted in Europe since at least the Middle Ages, was exacerbated by significant movements of Jewish populations from the East to the West in the nineteenth century. More recently, anti-Western sentiment, which drove the Khmer Rouge in the Cambodian genocide, continues to inspire radical Islamist groups today in North Africa and the Middle East.

The Holocaust and Genocides in Europe puts forward several interesting theories on the causes and processes of genocide, which deserve further examination. The comparative method enables Lieberman to put forward his ideas by narrating events in different cases, but I feel he would have been more convincing if he aimed this study to a more advanced audience, which would allow him to be more analytical and persuasive.

———————————————————–

Caroline Varin obtained her PhD in International Relations from the London School of Economics and is currently working as an intelligence analyst for sub-Saharan Africa. Her areas of interest include security, terrorism studies, military affairs and intelligence gathering. Read more reviews by Caroline.

2 Comments