Following success in the recent European elections, the UK Independence Party (UKIP) is the most significant new party in British politics for a generation. In Revolt on the Right, Robert Ford and Matthew Goodwin put UKIP’s revolt under the microscope and aim to show how many conventional wisdoms about the party and the radical right are wrong. The book offers a thorough analysis of a movement that has until now received only limited scholarly attention, writes Lise Herman.

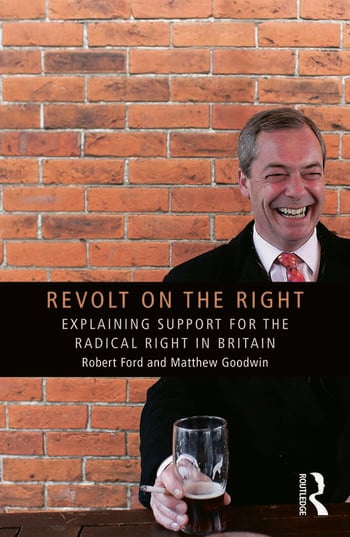

Revolt on the Right: Explaining support for the Radical Right in Britain. Robert Ford and Matthew J. Goodwin. Routledge. March 2014.

Revolt on the Right: Explaining support for the Radical Right in Britain. Robert Ford and Matthew J. Goodwin. Routledge. March 2014.

With UKIP’s recent triumph in the 2014 European elections, the recent publication of Revolt on the Right: Explaining Support for the Radical Right in Britain could not have been more timely. Robert Ford and Matthew J. Goodwin trace one of the major phenomenon of British politics over the last two decades: the transformation of a single-issue pressure group that David Cameron once described as a bunch of ‘fruitcakes, loonies and closet racists’ into a fully-fledged political party with national reach.

Indeed, beyond the double-digit results obtained in the last three European Parliament elections, UKIP has further proved its political credentials in a series of parliamentary by-elections between 2011 and 2013, and unprecedented results in the 2013 local elections. This evolution is all the more remarkable given the historical stability of the British party system, a national identity still grounded in World War II anti-fascism, and the institutional hurdles imposed by Britain’s first-past-the-post electoral system. Combining an approachable statistical analysis of UKIP’s electoral basis over the period 2004-2013 with first-hand testimonies from both elite and grass-root artisans of the movement’s success, this work delivers a comprehensive analysis of the dynamics underlying contemporary support for the radical-right in Britain.

The study’s first two chapters offer a chronological account of the successes and misfortunes of UKIP from its foundation in December 1993 up to the present day. Media coverage, academic studies, and interviews with key insiders – including founder Alan Sked, former figurehead Robert Kilroy-Silk, and current leader Nigel Farage – provide material for this detailed history of the movement. In a colourful literary style, the authors paint precise pictures of the major events and personalities that have contributed to shaping the party. These include, for instance, a vivid description of the heated atmosphere of a UKIP meeting that united 900 activists in January 2000, and an analysis of the pivotal role of former Conservative MP Roger Knapman’s leadership between 2002 and 2006 in professionalizing UKIP’s campaign strategies.

Ford and Goodwin also offer insight on the divisions that have perpetually affected the organisation. Beyond the ego clashes inherent to party political life, the study convincingly demonstrates the existence of more profound internal tensions over two key issues of party strategy and ideological positioning. The first concerns the way in which the organisation relates to the British National Party. Indeed, while the UKIP leadership has always been anxious to distance their platform from the more openly xenophobic stances of these radical counterparts, building this ‘reputational shield’ has proved a complicated endeavour. Not only have political adversaries been keen to point towards overlaps in the two parties’ ideas, electorates, and militant base, but in 2007-2008 this common ground also sparked demands within UKIP’s National Executive Committee for the conclusion of informal alliances with the BNP. A second ambivalence underlined by the authors concerns UKIP’s broader political objectives, and the party’s attitude towards the conquest of power. A share of their leaders and activists still perceive Britain’s distancing from the EU as a prime political objective, in line with the party’s enduring reputation as a single-issue pressure group. This has contradicted the ambitions of those, such as Nigel Farage, who advocate campaigning on a broader platform. It has also sparked regular dissensions over whether UKIP should informally ally with Eurosceptic hardliners within the Conservative party.

The remaining chapters provide a more traditional analysis of the wider social and political trends within which the UKIP vote can be interpreted. In chapter 3, the authors blend social cleavage theory with a spatial analysis of trends in voting behaviour to explain the rise of UKIP; a type of reading party scholars will be familiar with. Their point of departure is thus the deindustrialization and tertiarisation of the British economy, the decline in the traditional working class electorate and rise of the middle-class, and a resultant shift in concerns of the ‘median voter’ towards post-material values. Responding to these changes, mainstream parties would have broadened their appeals to address this growing middle-class, leaving behind voters disgruntled with the platforms of economic moderation and cultural liberalism mainstream parties have increasingly come to share. This is the population that would be forming the bulk of UKIP’s support.

In chapter 4 and 5, the authors support this analysis by providing an overview of the sociological and attitudinal traits of UKIP supporters. Relying on the British Election Study’s (BES) monthly-run Continuing Monitoring Survey (CMS), the study accounts for the responses of 5593 participants who declared their intention to vote UKIP in the following elections over the period 2004-2013. In line with the results of a wealth of studies on the socio-demographic characteristics of far-right electorates in Europe, the study shows that UKIP voters are more working class than the average population, have less formal education, and are predominantly male. The attitudinal traits of this group also closely resemble those of other far-right electorates in Europe. UKIP voters are first and foremost eurosceptics, but they are also either strongly positioned against immigration, and/or reject mainstream politics and politicians. They are also more likely to cast negative judgements on mainstream party performance. There are a number of more surprising findings in this analysis. The reader discovers, for instance, that over the years UKIP has won voters from both Labour and the Conservative Party, albeit more from the latter, and that dislike for the personality of David Cameron has played an important part in the recent surge for UKIP support. 57% of UKIP voters are above 55 years old, contradicting the wider European trend of a relatively young far right electorate.

Revolt on the Right offers a thorough analysis of a movement that has until now received only limited scholarly attention. While, to this extent, the study fills a clear gap, it may disappoint those looking for a broader theoretical contribution to the vast literature on radical-right parties in Europe. Generally speaking, the authors engage very little with this literature, making only passing mention to the way in which UKIP compares to other European far-right movements, and to existing theoretical frameworks that have helped explain surges of support for them. Chapter 3, for instance, develops the idea of a ‘competitive space’ left open by mainstream parties and successfully exploited by the far right. But the authors make no mention of Herbert Kitschelt’s work, whose argument is mirrored here, or even to spatial theories of voting more generally. And while the authors argue at several points that their perspective counters the ‘conventional wisdom’ on UKIP, their analysis endorses, in fact, a common reading of right-wing support as the ‘outgrowth’ of wider social and attitudinal changes mainstream elites have failed to capitalize on.

This is all the more regrettable that the very strong analysis and nuanced understanding of the development of UKIP’s strategy since its foundation in the first two chapters of the book offered this study a very strong potential for theory-building. Based on these findings, it could have made a more marked contribution to an emerging body of work on the European radical-right, which attempts to articulate the ‘demand’ for these organisations (the sociological and attitudinal pre-conditions for their success) and the ‘supply’ of far right-wing parties (how these organisations capitalize on these pre-conditions).

————————————-

Lise Esther Herman is a PhD candidate at the London School of Economics and Political Science, European Institute. She studies contemporary party politics in Europe, with a specific focus on the political identities of grass-root party members in the French and Hungarian political mainstream. Read more reviews by Lise.

4 Comments