Characterised by fractured political elites and fraught economic policies, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran and Iraq embody a mosaic of ethnicities. Amin Saikal, a distinguished Afghan-born scholar of international affairs, aims to provide a sweeping new understanding of the complex contemporary political and social instability encompassing the region. Caroline Varin finds this a topical and important book.

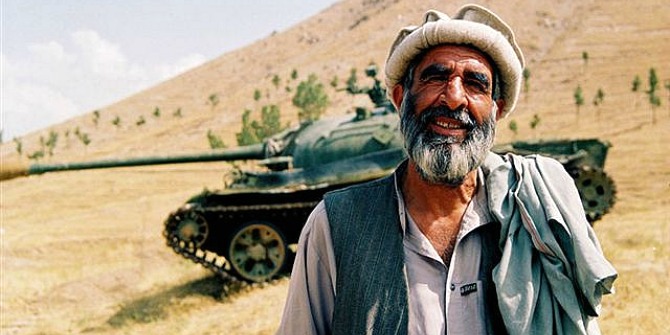

Situated at the fault lines between Asia and Europe, the countries of Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran and Iraq share the symptoms of a history of foreign invasions. All have been minor players in a ‘Great Game’ where rivals including Tsarist and Soviet Russia, Great Britain and the United States have competed for influence in the region. With their borders shaped by external powers, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran and Iraq continue to suffer from the legacies of the past and the ongoing interest of distant neighbours.

In Zone of Crisis, Amin Saikal – Professor of Political Science and Director of the Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies at the Australian National University – introduces the region and highlights the problems that obstruct the development and stability of each of these four countries. This is a relatively short book to cover such a vast and complex region, and Saikal’s focus on the political and social upheaval post-2001 leaves out a necessary analysis of historical developments. Nonetheless, he offers some ideas for how each country can move forward, suggesting that the ongoing chaos characteristic of the area is not inevitable.

Perhaps the most original contribution of this book, beyond assessing the similarities and differences between Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran and Iraq, is the realization that all four countries are irrevocably interdependent. Saikal shows that the fate of each country over this stretch of over 1,500 km depends very much on the political will of their immediate neighbours. For example, Afghanistan finds itself constrained by two ambitious countries, Iran and Pakistan, who are competing for influence in the region by supporting opposing militant groups in Afghan territory. In addition, each state is embroiled in separate territorial clashes with other countries, such as the Indo-Pakistani dispute over Kashmir. Finally, elite manipulation of ethnic differences continues to fuel civil and cross-border conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq and Pakistan. As Saikal puts it “every political decision ripples across the landscape to surrounding nations, with destabilizing effects that often create zones of conflict” (p.184).

The instability in the region is exacerbated by endemic corruption and fragmented political elites in all four countries. Saikal laments the lack of strong leadership, a problem in most of the world today. He highlights the greedy and self-serving attitudes of politicians, which have led to a rise in “patronage, corruption and inefficiency in both the civilian and military spheres at all levels” (p.35). In the cases of Afghanistan and Iraq, he strongly lays the blame on poor and short-sighted US policies, which have enabled the arguably corrupt leadership of Karzai and al-Maliki. However, Iran and Pakistan also suffer from a dysfunctional and fragmented elite due in large part to ethnic and religious differences among the population

Political failure inevitably leads to economic mismanagement, a problem that Iran, Iraq, Pakistan and Afghanistan all share. A recurrent issue seems to be the inefficient and elitist taxation system. Taxes make up just 7% of Iran’s GDP, with 50% of the population exempt and the rest mostly evading taxation. Likewise, only 2% of the population in Pakistan pays taxes. This has inevitable consequences on the public sector with reduced spending in education and health care. In the case of Iran, the economic plight has been exacerbated by international sanctions (as a consequence of its adamant pursuit of its nuclear enrichment programme). The other three countries have become increasingly dependent on foreign and especially US aid, thereby perpetuating the trend of external actors shaping domestic policies.

Saikal dedicates a considerable part of the book to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and US interference in Pakistan and Iran. This does come at the cost of further analysis on the ethnic dynamics and historical legacies in the region which are arguably essential for a thorough understanding. Saikal criticizes America’s democratization agenda in the area, and argues that policies have been implemented without a thorough review and understanding of the complex dynamics affecting each country. He does strike a positive note, however, by arguing that pluralistic and inclusive foreign support is indeed desirable and necessary to enable sustainable development in West Asia. Foreign interference in the 21st century is unavoidable.

Zone of Crisis is an important and topical book, particularly in view of the problems facing contemporary society. The divide between secularists and Islamists continues to widen, with extremists actively seeking to grab territory and topple governments. The relative military successes of ISIS in Iraq and the Taliban in Afghanistan are the result of failing policies, a fractured political elite and foreign interventions that weakened the state and left a gap for non-state actors to step into. Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran and Iraq will always be on the fault lines between the East and the West, and will thereby continue to attract the attention of great powers seeking to determine the fate of the international system, with inevitable consequences.

Caroline Varin is a lecturer at Regent’s University where she specialises in global conflict and international security. She received her PhD from the London School of Economics and is the author of Mercenaries, Hybrid Armies and National Security, forthcoming from Routledge. Read more reviews by Caroline.

2 Comments