The Food History Reader is a very welcome addition to the field of food history and will serve as a most valuable text to introduce students and researchers alike to the innumerable possibilities afforded by the study of documents which discuss historical food consumption. Josie Freear finds that it will be essential reading for any university course on the subject and will also appeal to a wider audience interested in how what we eat today has been shaped by the food practices of the past.

The Food History Reader. Ken Albala. Bloomsbury. 2014.

The Food History Reader. Ken Albala. Bloomsbury. 2014.

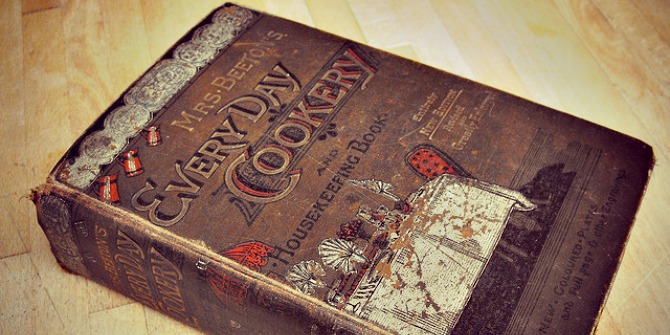

From Medieval Islam to McDonalds, Ken Albala’s thoughtfully curated selection of primary sources exemplifies the wealth of material available to researchers of food history. This collection of excerpts from written historical documents, spanning recorded human history and ranging from Herodotus and the Egyptian Book of the Dead to Mrs Beeton and Rousseau, serves to illustrate the myriad opportunities offered by using food as a lens to explore cultural, social, and political history.

The author is particularly well-qualified to command this material, as he founded a course in the Global History of Food over a decade ago at the University of the Pacific and has published not only monographs, edited volumes, and research papers, but also fully-fledged cookery books. His considerable experience in the field of food history is brought to bear with this history reader, and his enthusiasm for the subject matter is imbued in the breadth and quality of the written sources assembled in this book. For those new to the area or for those just seeking inspiration, this text serves as a useful starting point for stimulating discussion and a convenient reference book for seminal cultural and political writings and core religious texts concerning food, eating and diet.

One of the key areas of interest in this collection are the sources which discuss the relationship between individuals, food and health. The texts that deal directly with this theme find a common viewpoint in that they assign particular foods as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ for the health of individuals. These include an excerpt from Galen on the principles of humoral theory as a means of understanding the properties of different foodstuffs, Ayuverdic medicine in Ancient India, and Maimonides’ twelfth-century ‘Regimen of Health’. A seventeenth-century coffee advertisements expounds the use of coffee as a cure for ‘Dropsy, Gout and Scurvy’ and serves to illustrate the continuity of the application of humoral theory into the modern era. A related theme within the sources is the discussion of food as it relates to notions of purity and hygiene. These documents invoke Mary Douglas’ idea of dirt as being ‘matter out of place’ and aid our understanding of cultural constructions of cleanliness.

The chapters on the nineteenth-century industrial era and the twentieth century contain sources which chart the transformation of western nations from agrarian production-based economies to consumer societies. In the former, the documents range from social commentaries on welfare and excerpts from books on household management to key texts concerning the rise of food science and nutrition. Dietary reformer Sylvester Graham’s A Treatise on Bread, and Bread Making gives us insights into the constructions of gender norms in mid-nineteenth century American society. Elsewhere, Wilbur Atwater’s pioneering work on nutrition, which brought food’s calorific values to public attention, is particularly illuminating when viewed alongside the excerpt on Fletcherism, an early precursor to fad diets.

The final chapter looks at sources from the twentieth century and, whilst valuable for understanding the dominant influence of US consumer culture, is perhaps too limited in scope to give a comprehensive overview of the century’s rich food history. Whilst the material, solely published in America, has notable highlights, there is not much here for historians of British, European or ‘Global’ food history. An excerpt from Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle is one such highlight in this concluding chapter and proves to be particularly pertinent in light of the recent food fraud scandal. The source explains the networks of early-twentieth-century pork distribution and shows how these complex foodways resulted in old, mouldy sausages being sent back from Europe to be ‘dosed with borax and glycerine, and dumped into the hoppers, and made over again for home consumption’.

Whilst fans of the Great British Bake Off and historical cookery programmes will find plenty to whet their intellectual appetites, with eighteenth-century instructions for ‘how to dress a turtle’ and Mrs Beeton’s list of seasonal produce reproduced in full, the lack of visual sources and brevity of contextual information mean that a great deal of further research is required on the part of the reader if these sources are to be usefully understood. Albala’s intentionally minimalist approach to introducing the excerpts gives readers the bare essentials and leaves interpretation of the documents wide open for debate.

The real strength of this book is the richness and variety of the sources presented, for which Albala must be highly commended. Arranging these historical documents side by side encourages readers to make intertextual links and to identify trends, patterns and continuities in food history that might otherwise go unnoticed. It contains a comprehensive bibliography of both primary and secondary sources which will serve as a useful point of reference for researchers and provide a solid grounding in the relevant literature for students.

The Food History Reader is a very welcome addition to the field of food history and will serve as a most valuable text to introduce students and researchers alike to the innumerable possibilities afforded by the study of documents which discuss historical food consumption. It will be essential reading for any university course on the subject and will also appeal to a wider audience interested in how what we eat today has been shaped by the food practices of the past.

Josie Freear is currently completing her PhD thesis at the University of Leeds, focussing on the social history of food in twentieth-century Britain. She explores the role that food retailers have played in shaping the British diet since the 1950s. She is also a Research Assistant on the AHRC funded project ‘Climate Change, Ethics and Responsibility: an interdisciplinary approach’, where she is exploring what can be learned from rationing and ideas of fairness during the Second World War and applied to future debates on the regulation of carbon in response to climate change. Read more reviews by Josie.

Modern diets have changed radically from what our ancestors used to eat – and with the change has come an exponential increase in the numbers of people dying from such conditions as high blood pressure, heart disease, arthritis, gout, diabetes, etc. At a time when diets such as the paleo (caveman) diet are becoming increasingly popular Ken Albala’s book is quite timely.