Fantasy Islands aims to explore Chinese, European, and American eco-desire and eco-technological dreams, and examines the solutions they offer to environmental degradation in this age of global economic change. Michael Veale finds this a refreshing read.

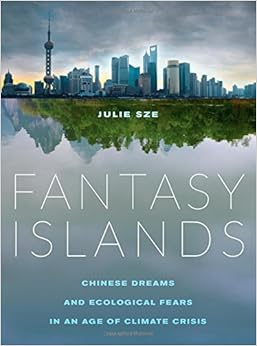

Fantasy Islands: Chinese dreams and ecological fears in an age of climate crisis. Julie Sze. University of California Press. 2014.

Fantasy Islands: Chinese dreams and ecological fears in an age of climate crisis. Julie Sze. University of California Press. 2014.

Julie Sze, a born-and-bred New Yorker and an American Studies scholar, subtitles her book Fantasy Islands as ‘Chinese Dreams and Ecological Fears in an Age of Climate Crisis’. This could, however, be misleading – her focus is not as much on these dreams and fears as the grey, occasionally contradictory, and often outlandish space that lies in-between. There is a gap powered by ‘eco-desire’ – a desire for harmonic physical spaces “somehow both rural and urban, Chinese and cosmopolitan, natural and artificial” (p. 17). Straddling these dreams and fears, Sze shows us the residents, businesses and developers hoping for an eco-utopian Shanghai full of green consumption, bird-song, and technological solutions to the staggering array of sustainability issues that China’s rapid development has left in its wake.

With a narrative approach, Sze explores the story of the postponed eco-city of Dongtan, an ambitious planof British engineering consultants Arup situated on the mud-flats of Chongming island, a little way north-east of central Shanghai in the mouth of the Yangtze river. Sze’s family originally hail from this island, albeit a different section, and her consequent curiosity to better understand rings clear. Chongming’s “rural character, open space, underdevelopment and lack of industry” are economic assets in ‘natural capital’ inspired discussions of Dongtan’s development. Dongtan would showcase the potential of technological solutions to solve the major environmental issues of the day. Today however, the Dongtan site consists only of 10 wind turbines, rather than a low-rise, food self-sufficient city, dotted with water taxis ferrying people to apartments surrounded by greenery. The Communist Party project co-ordinator was imprisoned for corruption and Arup came strongly under fire — their website shows little trace that they were ever involved in such a project. But this book is about the mindset that led to those plans, similar, existing developments around Shanghai, and the eco-utopian picture portrayed by the 2010 World Expo.

The pitch for Dongtan was a simplified ecological fairytale. Dark forces of pollution and urbanisation victimise birds, who are saved by heroes commanding cutting edge science, technology, and planning. Chinese suburbanisation has eco-characteristics, just as its urbanisation does. A journey through the eco-marketing deployed by the unsettling Shanghai satellite commuter towns of the ‘One City, Nine Towns’ project, each one designed by a different international firm in the styles of countries such as England, Germany, Sweden or Spain, further illustrates the tangle of local and global, the technological and the historical. The English development, Thames Town, equipped with a statue of Winston Churchill and red phone boxes, asks residents to “enjoy sunlight, enjoy nature, enjoy your life & holiday, dreaming of Britain“. Banners advertising “Low Carbon: The Original Ecological German Style Apartments” appeal to new property-hunters in the German town An Ting, who after half a century can now choose where they live. Green is high quality and green is luxury, and green is a selling point in changing Chinese real estate markets.

Yet Sze notes that the concept of ‘eco’ is by no means uniform. She interviews farmers displaced by the aborted development, confused that ‘eco-buildings’ they were moved to do not even use renewable energy, and inhabitants of Chongming island, who seem to equate the idea of an eco-island with an offshore financial centre. She describes the visual plans for Dongtan, which despite aiming to be ‘a Chinese City for the Chinese’, are laden with images of white inhabitants and élites, representing “Western modernity, but also, more precisely, an advanced, developed, and privileged social position and lifestyle” (p. 95-96).

Of course, the world teams with products claiming sustainability from countless different angles. That the differences in perceptions also exist in China is not particularly new or shocking, nor is the technological faith and fetishism, which is to be expected of a country which plans big and top-down, America’s very “enemy and [its] salvation” (p. 26). Striking from this book is the role post-materialist values play when a significant subset of a country’s citizens leapfrog to unprecedented levels of spending power and choice. Many purely economic theories of innovation hinge on the cost difference between invention and imitation. However in the Chinese case, we are shown an industry that can imitate technology while leading in conceptual scale, driven by an eco-desire which is partially an imitation of post-materialist concerns in Western markets, and part-driven by very Chinese experiences of development and environmental degradation. This combination does not seem to play well with existing mainstream theories, and narrative style studies like Sze’s can strengthen the foundations of future theorising considerably.

Absent from this work however is an engaging discussion of rigour and marketing in sustainability claims. While Sze critiques eco-cities as not challenging the systems of production that underpin the environmental crisis, she does not devote many inches to the actual or potential consequences of the developments themselves. Wide literatures, mostly focussing on the West but with some related to China or Taiwan, exist on the determinants and consequences of ‘green-washing’ (substance-free environmental claims solely for marketing purposes), yet many are highly econometric in nature (this paper, this paper, or this paper for example). A more qualitative, discursive method, especially in rapidly-industrialising and economically important countries such as China, would be an important addition to our understanding of how new consumers in these key economies are persuaded by green claims.

In sum, this book is recommended reading for both those trying to get to grips with green purchasing in developing countries, as well as those interested in what the people on the street think of planning green and thinking huge. It is also a refreshing read compared to media coverage on the issue, which tends to label developments as “hilarous” or “bizarre”, or just interview the big names involved, without providing much on-the-ground insight.

Michael Veale has a bachelor’s degree in Government and Economics from LSE and a master’s degree in Sustainability Science and Policy from Maastricht University. His main research interests are sustainability at the border of science and policy, private governance and certification, data visualisation, stakeholder participation and innovation. He is currently gathering experience in real-world public and private policymaking before hoping to return to academia to co-create some useful insights into complex problems.

2 Comments