Can the study of peace be separated from the study of war? In The Question of Peace in Modern Political Thought, editors Toivo Koivukoski and David Edward Tabachnick attempt to present an interrogation of peace as an independent strand of philosophical inquiry. While Alexander Blanchard suggests that challenging the conflation of the study of war and of peace may not be fully achieved, he welcomes the volume for exploring philosophers not usually associated with the concept of peace and for providing timely reflections on the question of cosmopolitan rights in the light of the current refugee crisis.

The Question of Peace in Modern Political Thought. Toivo Koivukoski and David Edward Tabachnick (eds). Wilfrid Laurier University Press. 2015.

It is strange that the question and the idea of peace, so recurrent and supposedly so important to us, have not received the refinement they deserve. Publicly, the way that peace is discussed and venerated is usually glib, inconsequential or even duplicitous: ‘Peace is a journey of a thousand miles and it must be taken one step at a time,’ said US President Lyndon B. Johnson, not too long before escalating the war in Vietnam. Perhaps this was a natural consequence of political language, but in political thought, social thought and philosophy, the question of peace has, on the contrary, been historically neglected. This neglect may be the result of two factors. Firstly, that peace has been thought about under a different rubric, or analogously, such as through utopian literature. Secondly, that the concept of peace has been subsumed under the more enthralling concept of ‘war’.

It is strange that the question and the idea of peace, so recurrent and supposedly so important to us, have not received the refinement they deserve. Publicly, the way that peace is discussed and venerated is usually glib, inconsequential or even duplicitous: ‘Peace is a journey of a thousand miles and it must be taken one step at a time,’ said US President Lyndon B. Johnson, not too long before escalating the war in Vietnam. Perhaps this was a natural consequence of political language, but in political thought, social thought and philosophy, the question of peace has, on the contrary, been historically neglected. This neglect may be the result of two factors. Firstly, that peace has been thought about under a different rubric, or analogously, such as through utopian literature. Secondly, that the concept of peace has been subsumed under the more enthralling concept of ‘war’.

The Question of Peace in Modern Political Thought contains a selection of essays that consider the contribution that has been made to our understanding of peace by those modern philosophers – from Martin Luther in the sixteenth century to Jürgen Habermas in our present century – who, though outstanding in the Western politico-philosophical tradition (there are no Eastern thinkers in this volume), are neither known for, nor set out, an explicit theory of peace (perhaps with the one exception of Immanuel Kant). From the outset, it is commendable that the editors of this volume, Toivo Koivukoski and David Edward Tabachnick, recognise the need to address the aforementioned conceptual conflation by separating an inquiry into the idea of peace from one into the idea of war. As they warn in their introduction: ‘it is insufficient for us to define peace simply in terms of what it is not, or else peace studies may morph into the study of war’ (12).

It is no fault of the authors whose essays comprise this volume that this separation is largely unachieved. Rather, it is an indication of the staying power that war has had within the Western philosophical tradition and the minds of its most principal thinkers – almost invariably men, regrettably. Thomas Hobbes, obsessed with the frightful reality of war in his own time, allowed his work to become possessed by the idea of it. John Locke began his ruminations on peace from the foundational principle that one’s ‘natural’ love of domination needs to be tempered. The dialectician Hegel believed that war is inevitable; that reason demands it; and that it is, therefore, in some ways desirable. The ontology of that apologist for Nazism, Martin Heidegger, led him to think ‘that a massive perpetration of external violence would in some way recapture a nearly lost ‘‘inner harmony’’’ (183). Jean-Jacques Rousseau recognised peace as having a much more extended significance than merely as an opposite to war as one can ‘interrupt and disturb the peace in several ways without proceeding as far as war’ (110). And yet, even Rousseau, greatly impressed by Hobbes, established the war of all against all in his own notion of amour-propre, and therefore failed to release peace from its opposite.

It seems that raiding the canon of philosophy for creative and original insight into peace was always going to be something of a doomed endeavour. Nevertheless, this volume contains some fine essays, notably by Benjamin Holland on Emer de Vattel and morally non-discriminatory peace, Toivo Koivukoski on Henry David Thoreau and seeking peace in nature and Hermínio Meireles Teixeira on Walter Benjamin and divine violence, an essay that explores with great clarity and dexterity some extremely complex and difficult ideas. But, as one reads over this set of essays, and as one sees the so-called refugee crisis unfold across Europe, it is Leah Bradshaw’s essay on ‘Kant, Cosmopolitan Right, and the Prospects for Global Peace’ that appears most compelling and timely.

Today we live with an antagonistic set of assumptions: the fundamental equality and autonomy of human beings on the one hand and, on the other, the claims of state sovereignty and religious, ethnic and racial identifications. It is more than just prophetic that Kant, writing during the Enlightenment before this thing we call ‘globalisation’, saw how pertinent this antagonism would become as the worldwide movement of people increased. Moreover, he saw something which the ideas that grew out of the French revolution have in some way obscured: although universal rights can be embraced by reason, they are upheld only by state institutions, by law and by force. Rights are not inalienable; they are political. Hannah Arendt, a refugee herself and a follower of Kant, stated much the same when she wrote that ‘the calamity of the rightless is not that they are deprived of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness […] but that they no longer belong to any community whatsoever’ (136).

Bradshaw asks how one rescues those that have lost their rights and the protection of a political community. The EU’s appalling response to the refugee crisis should be something of a worrying counter to those who advocate a cosmopolitan order comprised of international bodies and founded on the ‘right to have rights’ (139). Those ethnic, racial, religious and linguistic tensions which the EU has done little to ameliorate have seen many countries abrogate responsibility and shunt refugees across the continent. There are those, Bradshaw notes, who advocate adopting ‘a multiculturalism that adapts to the model of liberal nationhood’, a ‘“multination’’ conception of the state’ (141) in the same way that Kant saw the ‘entrenched differences among peoples as intrinsically linked to the modern sovereign state’ (142). Ultimately, and whatever the answer, Bradshaw’s analysis of Kant highlights an important concern for the modern Western polis.

For Kant, state-centred rights – citizenship – are the catalyst for cosmopolitan sentiment and right. Our fundamental obligation begins with the protection of external right within our political community, and this leads on to a defence of federations on the international level culminating in cosmopolitan right. Significantly, this structure cannot be inverted: ‘Cosmopolitanism is not the inspiration for the political protection of right’ (136). Moreover, ‘if states do not fulfil their mandate, the entire structure of right collapses’ (136). If, then, we in Europe (notably state institutions) are disinclined to protect cosmopolitan right, what might the fragility of our own fundamental political rights be were they to be tested? It is a frightening thought.

The Question of Peace in Modern Political Thought is to be highly recommended. Even those essays that do not provide the most incisive analysis of their subject – and this is predominantly because a number of essays are not given enough length to fully outline their contribution – provide a good introduction to those thinkers whom we do not normally associate with the idea of peace.

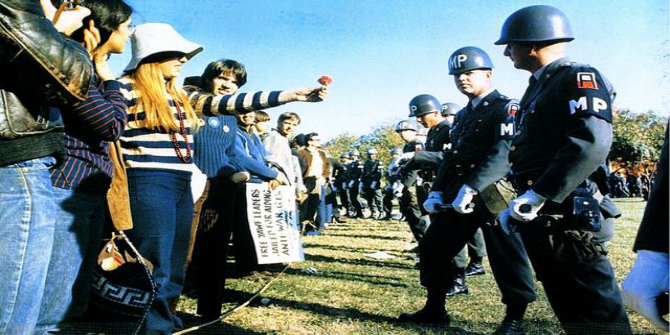

Image Credit: A demonstrator offers a flower to military police at a National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam sponsored protest in Arlington, Virginia, on 21 October 1967 (Wikipedia Public Domain)

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

2 Comments