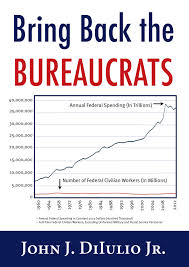

In Bring Back the Bureaucrats, John J. Dilulio Jr. concisely and passionately outlines the dangers of Big Government by stealth in the USA as bureaucratic tasks become increasingly outsourced to proxies including charities, business contractors and local government. Ruth Garland writes that the book resonates with current debates over the provision of public services in the UK and therefore opens up useful discussions for UK government-watchers as well as university students looking to explore these issues.

Bring Back the Bureaucrats. John J. DiIulio Jr. Templeton Press. 2014.

This short book about the dangers of Big Government by stealth in the US, written by a political scientist who proclaims his devotion to the principles of the Founding Fathers and his love for the US government, might seem parochial. In fact, John Dilulio’s argument, and the ‘blizzard of facts’ that he marshals to support it, resonate powerfully and repeatedly with the UK situation, where, we are told, public services must provide ‘more for less’. Only last month, the former Cabinet Secretary, Lord Andrew Turnbull (2002-05), accused the Chancellor George Osborne of using the rhetoric of debt control as a ‘smokescreen’ for a smaller state.

This short book about the dangers of Big Government by stealth in the US, written by a political scientist who proclaims his devotion to the principles of the Founding Fathers and his love for the US government, might seem parochial. In fact, John Dilulio’s argument, and the ‘blizzard of facts’ that he marshals to support it, resonate powerfully and repeatedly with the UK situation, where, we are told, public services must provide ‘more for less’. Only last month, the former Cabinet Secretary, Lord Andrew Turnbull (2002-05), accused the Chancellor George Osborne of using the rhetoric of debt control as a ‘smokescreen’ for a smaller state.

Dilulio argues passionately that while governments of all political colours like to claim, as Bill Clinton did in 1996, that ‘the era of big government is over’, in fact they are simply displacing the tasks formerly carried out by federal government employees onto more expensive, less effective and less controllable ‘proxies’, such as charities, business contractors and local government. The result is Leviathan by Proxy: a federal government that is ‘at once hyperactive and anemic, overgrown and understaffed’ (92).

In 2013, he states, the federal government spent $3.5 trillion – in real terms, five times more than it spent in 1960. Yet, by 2005, the number of civilian federal bureaucrats was around 1.8 million, the same number as in 1960. Dilulio is especially scathing about the administration of Medicaid, a means-tested programme that pays the medical expenses of people receiving welfare support. In 2011, Washington spent $275 billion and the states $157 billion on Medicaid – a service that is funded and administered via central and local government, but delivered largely by private contractors and the voluntary sector. As a proportion of GDP, the US spent 17.7% on healthcare in 2011, compared to an average for all OECD countries of 9.3%.

Other departments, too, are top-heavy with contractors: the Department of Homeland Security for example, has 200,000 contractors and only 188,000 employees. Dilulio argues that the massive expansion of outsourcing has left a shrunken, demoralised, de-skilled and undervalued federal bureaucracy to administer an increasingly complicated and unaccountable web of contractors, each of whom lobbies incessantly for the expansion of its own services. The result is a proliferation of ‘waste, fraud and abuse’ and ‘well-documented cases of federal agency fragmentation, overlap, duplication and forgone cost-savings’ (23).

The stranglehold over power wielded by the two-party system contains an inherent and ultimately unsustainable contradiction that makes it much harder to reverse the policy of Leviathan by Proxy than it was to unleash it in the first place. Democrats are the party of ‘benefit more’ and Republicans are the party of ‘tax less’, Dilulio claims, while Congress is addicted to action. He agrees with Martha Derthick, who said in 2001: ‘Congress loves action – it thrives on policy proclamation and goal setting – but it hates bureaucracy and taxes, which are the instruments of action’ (35). Congress has enacted 2,500 new laws and thousands of new rules and regulations since 1999: a situation the author describes as ‘uniquely American’.

Image Credit: Red Tape Dispenser (Lilly_M)

Image Credit: Red Tape Dispenser (Lilly_M)

In fact, this will feel uncomfortably familiar to UK government-watchers and especially to readers of Anthony King and Ivor Crewe’s influential book, The Blunders of Our Governments (2013), which chronicles a series of dramatic and expensive policy failures that owed more to political over-expectation than to evidence-based analysis. What both books fail to explore in any detail though, is why this might be happening. Dilulio hints that the widening gap between what politicians say they do, and what actually happens, is at least partly related to politicians’ media responsiveness and the media’s own anti-public sector bias, but he does not develop this argument. Similarly, he has an interesting view on the role of lobbyists employed by contractors to preserve their growing government-linked business interests, making it harder for politicians to clamp down on government expenditure on contractors. This too has profound implications for democratic and deliberative decision-making.

Again, Dilulio neither develops this into an argument about how an increasingly mediatised politics might make certain policy decisions difficult or even impossible, nor does he examine the connection between private contractors’ business interests and those of some politicians. In fact, he largely excludes the profit motive from the discussion, taking an equivocal approach to profit and non-profit government contractors. He suggests that checks and balances within European political and administrative systems, including those of the UK, appear to be more successful in upholding the public interest in relation to contractors. We saw an example earlier this year in the recent crisis at the UK voluntary sector service provider, Kids Company, where a highly successful engagement with leading politicians over decades met resistance from accountable officers within the Civil Service, leading to the decision to pull the plug on government funding and the closure of the agency, but this may be the exception rather than the rule.

Dilulio contends that the consequences of Leviathan by Proxy are extremely serious: the practical impossibility of monitoring this ‘vastly complicated’ edifice (7) is undermining the democratic accountability of public administration and bringing about ‘the derangement of our constitutional system’ (24). His solution is the title of this book.

At just 142 pages, and with plenty of passion and colourful phrases, Bring Back the Bureaucrats could easily be read over a weekend by the average over-stretched bureaucrat. It is not an academic book, but is full of clearly presented and pertinent facts that would provide a useful starting point for discussion for university students.

Ruth Garland is a researcher and PhD student in Media and Communications at the London School of Economics, looking into UK government communications. Read more reviews by Ruth Garland.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

1 Comments