Despite the severity of Enver Hoxha’s regime as Albanian leader between 1944-85, relatively little has been written about him. In Enver Hoxha: The Iron Fist of Albania, Blendi Fevziu provides the first English-language biography of the dictator, drawing upon hitherto unseen documents, first-hand interviews and Hoxha’s own writings and memoirs. Simeon Mitropolitski particularly recommends this read to those looking to widen their understanding and knowledge of Albania and its history.

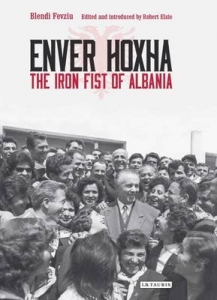

Enver Hoxha: The Iron Fist of Albania. Blendi Fevziu (trans. by Majlinde Nishku). I.B. Tauris. 2016.

In his book Enver Hoxha: The Iron Fist of Albania, Albanian journalist Blendi Fevziu presents English-language readers with the first comprehensive account of the life of the longest ruling communist leader in Eastern Europe (the original, Albanian-language version was published in 2011 after a series of TV programmes by Fevziu in the early 2000s). The author summarises his goal as painting the portrait of a real person, of what Hoxha was really like (3), without exaggeration, unjustified denigration or bias (9). Throughout the book we find the image of a ruthless and skillful politician using any misstep by other leaders for his own advantage. This interpretation may seem exaggerated for an ordinary politician, but Hoxha indeed rose to absolute power, and the system created by him survived beyond the end of his life for some years.

In his book Enver Hoxha: The Iron Fist of Albania, Albanian journalist Blendi Fevziu presents English-language readers with the first comprehensive account of the life of the longest ruling communist leader in Eastern Europe (the original, Albanian-language version was published in 2011 after a series of TV programmes by Fevziu in the early 2000s). The author summarises his goal as painting the portrait of a real person, of what Hoxha was really like (3), without exaggeration, unjustified denigration or bias (9). Throughout the book we find the image of a ruthless and skillful politician using any misstep by other leaders for his own advantage. This interpretation may seem exaggerated for an ordinary politician, but Hoxha indeed rose to absolute power, and the system created by him survived beyond the end of his life for some years.

Methodologically, the book is based on a multitude of primary sources, some published under communism and others after its end. The Albanian leader, through eighty publications including thirteen volumes of memoirs, set out the main milestones of his life, leaving his biographers with the uphill task of challenging his interpretation of events. Memoirs of Hoxha’s political friends and adversaries represent another layer of documents that either confirm or reject the dictator’s interpretation of more than forty years of Albanian history. The formerly secret Albanian state archives, open since the early 1990s, add a completely new dimension that puts in context and often challenges the memoirs. Last but not least, the author, as an investigative journalist, gathers important information from people who witnessed some of the events firsthand.

The structure of the book does not strictly follow the life of Hoxha chronologically. It begins with the days before his death in April 1985 and ends in May 1992, when his remains were transferred to the Tirana municipal cemetery. In between, the author tells the story of a French lycée student from a bourgeois family who climbs the stairway of power; of a communist fighting Italian and German occupation; and of a leader keeping power for the rest of his life, blocking every real and imaginary threat, both domestic and international.

Several chapters deal with Hoxha’s physical elimination of his adversaries. This process began in the 1940s, when Albania was still under foreign occupation, and ended forty years later after the prime minister, Mehmet Shehu, committed suicide in 1981. Another narrative concerns Hoxha’s foreign policy, moving from close relations with the Yugoslav leader, Tito, to taking sides with Joseph Stalin against Tito and then siding with China against Moscow, until finally fully isolating Albania from the rest of the world. This part of Hoxha’s biography is well-documented by the dictator himself, who dedicated a number of memoirs to his relations with the leaders in Belgrade, Moscow and Beijing. It is as if Hoxha, listening to British wartime leader Winston Churchill’s advice, wanted to make history kind to him by writing it himself.

Image Credit: ‘Tirana – Enver Hoxha souvenirs’ by Andreas Lehner licensed under CC BY 2.0

Image Credit: ‘Tirana – Enver Hoxha souvenirs’ by Andreas Lehner licensed under CC BY 2.0

I found particularly captivating the chapters of the book in which Hoxha is shown more as a real life person, either through detailing his interactions with his closest friends and family or through his actions on matters relatively apart from pure politics. That is where his personality becomes richer and contradictory, where standard clichés about the absolute tyrant become questionable. Hoxha leads people to the brink of the abyss and then suddenly backs off, lending them a helping hand. The example with famous writer Ismail Kadare is telling in this respect. Informed of Kadare’s intention of writing a book on the breakdown of Albanian-Soviet relations, Hoxha (through his wife) invited Kadare and his wife to his home, where he shared with the writer his views on the events. Kadare’s The Great Winter later used this firsthand testimony in the chapter ‘Dinner in the Kremlin’. Even though Hoxha had given his blessing, no sooner had the book been published in 1973 than a vociferous campaign was unleashed against it and its author. Suddenly Hoxha, without whom this condemnation would have been impossible, unexpectedly rose in defence of Kadare and approved the book, while calling for minor corrections.

Saving Kadare from the trap laid down by Hoxha himself is not unique in the life of the Albanian dictator. Why play with his subjects? Why show generosity without any political reason? The author calls these episodes symptoms of a ‘split personality’ and dedicates an entire chapter to different cases that illustrate it. He never discusses the possibility that Hoxha had a comprehensive personality that found its best expression in brutal and generous actions. The book centres on brutality as a norm and presents the generosity as an exception. The first part of this statement is hard to challenge, given the mountain of evidence. The second part, however, is questionable, and it will leave readers puzzled and curious to learn more about the man who personified Albania for more than forty years.

This book targets the general public, not just specialists on Albania or on communist studies. The writing style does not include technical language and reading is also made easy thanks to the translation provided by Majlinda Nishku. In addition to the main text, the book includes a chronology of the life of Hoxha, a glossary of key figures, a section of notes, a bibliography and an index. These additional sections will help non-Albanian readers who otherwise may find themselves lost in the sea of names, dates and events.

Comparatively speaking, the communist period in Albania is not well studied within communist studies. To put the research interest toward this country in perspective, only 62 articles mentioning Albania were published in the journal Communist and Post-Communist Studies, compared to 158 on Bulgaria and 241 on Romania, two other Balkan former communist countries. In this respect, the present book fills a gap regarding communist Albania and provides fresh encouragement for those studying the history and current political developments of the country. Fortunately, this book goes beyond the narrative of bringing yet one more exotic country to modern political science. Albania provides a unique opportunity for comparative analysis of communist countries, an analysis that may jeopardise bounded generalisations regarding the countries from the Soviet bloc. The Albanian case also calls into question models in which certain patterns of communist development require the presence of mentally unstable leaders.

On a critical note, the book needs to go further beyond the simple accumulation of facts about the late Albanian dictator into the realm of contemporary politics. No doubt Albania, like any other country, wears vestiges of its past. The question that needs to be answered is: what kind of legacies left by Hoxha are still shaping Albania, an open multiparty political system and a member of NATO? The answer may be obvious for Albanian readers who feel these legacies and remember the totalitarian past; it is, however, not obvious for those who have never been to Albania, and especially for those for whom this book represents their first encounter with the country. Another weakness is letting the facts speak for themselves, a risky endeavour that may mislead readers. It would have been wiser to present the facts as illustrations for particular general arguments. In some chapters, for instance on political purges, the topics and arguments seem to overlap. In other chapters, however, such as on Hoxha’s foreign policy, the absence of the author’s own arguments is apparent.

These limitations notwithstanding, the book is a very useful read both for people curious to learn more about Albania, and also for those who will update their knowledge of one of the most mysterious post-communist countries in Europe.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Hoxha was a tyrant in all ways.