In Unruly Equality: US Anarchism in the 20th Century, Andrew Cornell traces a prehistory of the contemporary anarchist movement in the USA, showing anarchism to be a complex and evolving ideology that cannot be reduced to the pursuit of individual freedom. The book will be of use to those looking to concern themselves with both the historical role and future prospects of anarchism as a political movement, intellectual tradition and a way of life, writes Ioannis Papagaryfallou.

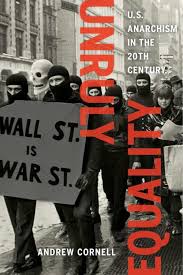

Unruly Equality: US Anarchism in the 20th Century. Andrew Cornell. University of California Press. 2016.

In Unruly Equality: US Anarchism in the 20th Century, the US anarchist and educator Andrew Cornell portrays anarchism as a complex and historically evolving ideology which cannot be reduced to the search for individual freedom. The writer’s primary historiographical purpose is to offer a prehistory of contemporary anarchism and to underline the importance of the period 1940-60, which is frequently seen as one of stagnation for the anarchist movement in the United States.

In Unruly Equality: US Anarchism in the 20th Century, the US anarchist and educator Andrew Cornell portrays anarchism as a complex and historically evolving ideology which cannot be reduced to the search for individual freedom. The writer’s primary historiographical purpose is to offer a prehistory of contemporary anarchism and to underline the importance of the period 1940-60, which is frequently seen as one of stagnation for the anarchist movement in the United States.

Although illuminating from a historiographical point of view, Cornell’s book arguably contains some overstretched claims regarding the importance of anarchism to the Left. It also tends to analyse anarchism’s complexity and heterogeneity in diachronic rather than synchronic terms; and often neglects the fact that even at a given historical moment, anarchism can mean different things to different people. Nevertheless, the writer’s association of anarchist ideas with a particular form of equality – an ‘unruly equality’ as he describes it – shows that anarchism is not so much an alternative to the Left than a corrective to its more hierarchical and bureaucratised expressions. Radicals in America and elsewhere should concern themselves more thoroughly with the historical role and the future prospects of anarchism, understood not only as a political movement but also as an intellectual tradition and a way of life.

The historical narrative of the book begins in the Progressive Era (1890-1920), during which US anarchists exerted an unprecedented social and political influence because of their links with organisations such as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and the cultural and educational activities of public personae such as Emma Goldman. Although this period represents the apogee of what Cornell defines as ‘classical anarchism’, a careful reading of the book reveals that even at this early point, anarchists were far from united regarding their priorities and the means of pursuing these.

Image Credit: (Lilian Wagdy , CC 2.0)

Image Credit: (Lilian Wagdy , CC 2.0)

The differences between anarcho-syndicalists, insurrectionists and bohemian anarchists were not academic in nature, but had significant consequences for the direction of the movement and the identity of the participants. The strategy of strikes and workplace sabotage implemented by the anarcho-syndicalists presupposed a more long-term point of view than the insurrectionist propaganda of the deed, and both syndicalists and insurrectionists felt uncomfortable with bohemian anarchists’ preoccupation with sexuality and personal self-expression. Indeed, the foundations of the contemporary alliance between anarchism and certain middle- class audiences were set by cultural innovators such as Goldman, whose social critique did not concern only the distribution of wealth and power, but also extended to issues that were later conceptualised as ‘biopolitical’, including the promotion of birth control and a more general emphasis on the rights of women.

Cornell’s somewhat harsh evaluation of the classical class-struggle-anarchism is broadly justified in the case of the interwar period where the anarchist movement in America did not make any significant progress because of a combination of state repression and internal disagreements. The entry of the United States into World War I and the subsequent threat of fascism divided anarchists and progressives alike, and made them abandon their earlier cultural explorations and experimentations.

For Cornell, the roots of contemporary anarchism – which appears fully formed by the early 1970s – should therefore be sought in the period 1940-60, a period characterised by osmosis between anarchists, pacifists and avant-garde artists. In the midst of total war and the gradual incorporation of the working class into socialised states that had little in common with their nineteenth-century liberal counterparts, the analyses of nineteenth-century thinkers and activists such as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Mikhail Bakunin started to seem outdated. Social revolution seemed very far away, and the state system threatened not only individual liberties but also the very survival of humanity. Anarchists able to take advantage of the findings of psychology and anthropology understood that the state does not rely exclusively on coercion, and that the material and immaterial structures underpinning domination cannot be wiped out by an act of will.

While Cornell’s emphasis on the years 1940-60 as the period when contemporary anarchism began to emerge makes sense, his arguments regarding anarchism’s supposed influence upon the American New Left are not particularly convincing. In an effort to save US anarchists from what E.P. Thompson in The Making of the English Working Class described as ‘the condescension of posterity’, Cornell leads the reader to the conclusion that anarchist ideas not only anticipated, but also accounted for the emergence of the various social movements comprising the New Left. The writer’s primary points of reference are the idea of participatory democracy and the libertarian agenda adopted by certain chapters of the organisation Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which was particularly influential during the 1960s.

However, to say that there are ways in which the transition from classical to contemporary anarchism resembles the transformation of the Old Left into the New Left is different from establishing causal relationships and connections. Because of its fluid and dynamic nature, anarchism was able to adapt to changing social conditions more quickly than the Left did, but this does not make participatory democracy by definition an anarchist idea. Indeed, the tension between anarchism as a form of radical democracy and anarchism as a belief in consensual decision-making remains largely unresolved in the book.

Although convincing and adequate as a prehistory of contemporary anarchism, Cornell’s book could have shed more light on events such as the ‘Battle of Seattle’ World Trade Organisation protests in 1999 and the broader global justice movement. In an effort to reconstruct a relatively unified anarchist tradition despite major intellectual and other departures, the writer does not explain how, for example, the ideal of nonviolence entertained by the activists of the 1940s was ultimately superseded by what today passes as black bloc tactics. The conceptualisation of anarchism as a form of participatory democracy certainly holds great scholarly promise, but it requires further theoretical elaboration and will probably have to overcome serious reservations within the anarchist movement. Not all anarchists would endorse a conceptualisation of anarchism that brings it close to democracy, however radical the latter may be. Finally, yet importantly, the book could have benefited from an examination of the different – and often conflicting – meanings that the idea of anarchy assumes today within the academic discourse of International Relations (IR). Anarchy ultimately is what people – and states – make of it.

Ioannis Papagaryfallou is a PhD candidate in the Department of International Relations at LSE. His research revolves around the relationship between history and theory and its consequences for the English School of International Relations as a research programme. Read more reviews by Ioannis Papagaryfallou.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.