On 15 April 1989, 96 people were crushed to death and another 766 injured at the Hillsborough Stadium, Sheffield, during an FA Cup semi-final between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest football clubs. Following new inquests, earlier this year a jury ruled that those who died in the disaster had been unlawfully killed. In Hillsborough Voices, Kevin Sampson – in association with the Hillsborough Justice Campaign – foregrounds the memories and first-hand testimonies of survivors, friends, families, footballers, campaigners and politicians. This is an extraordinarily powerful account told by those who have fought for 27 years for the truth to be known, writes Tim Newburn.

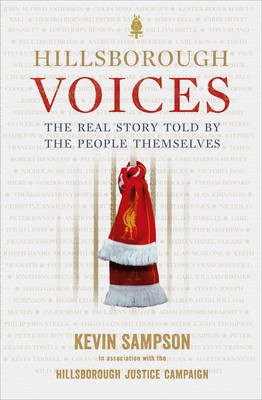

Hillsborough Voices: The Real Story Told By The People Themselves. Kevin Sampson (in association with the Hillsborough Justice Campaign). Ebury Press. 2016.

In light of the recent inquest verdicts, there are surely few who remain ignorant about what happened on 15 April 1989 at Sheffield Wednesday’s football ground during an FA Cup semi-final between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest. At least as importantly, there must now be far fewer than was once the case who remain ignorant as to the how and why.

In light of the recent inquest verdicts, there are surely few who remain ignorant about what happened on 15 April 1989 at Sheffield Wednesday’s football ground during an FA Cup semi-final between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest. At least as importantly, there must now be far fewer than was once the case who remain ignorant as to the how and why.

In short, 96 Liverpool fans died in an entirely avoidable crush and amidst scenes of chaos as the police and emergency services failed first to understand what was happening, and then failed entirely to cope with the unfolding disaster. They and others then compounded these horrific failures by the most extraordinary cover-up in which the fans themselves were blamed, the reputations of both those that died and those that survived were publicly traduced, and attempt after attempt by the families to have the truth made public was thwarted by dirty tricks that would hardly be out of place in the most tin-pot dictatorship.

This is the story in Kevin Sampson’s Hillsborough Voices: The Real Story Told By The People Themselves, an account of both the day itself and its aftermath, based on first-person testimony. Though I don’t know Sampson, we must have grown up fairly close to each other on Merseyside (he’s a couple of years younger than me). Certainly, his terrific first novel, Awaydays (1998), describes some of the more visceral realities of the Birkenhead of my youth all too authentically.

Following a career in music journalism and production, in television and as a highly successful novelist, Sampson has now brought his talents to bear on the scandal of Hillsborough. This book, though, is an oral history told through the words of only eighteen people – family members, survivors, footballers, campaigners and politicians – their voices woven together to tell the real story. Sampson himself hardly appears in the book, bar a short introduction where he writes of his experience of being at the match that day. He stands back, using his craft to construct a narrative that gives the individual stories space and respect, whilst simultaneously enabling the bigger picture to emerge.

Image Credit (Linksfuss CC 3.0)

Image Credit (Linksfuss CC 3.0)

It is a picture that began, as Sampson himself puts it, with Liverpool fans setting off on a fine spring morning ‘with hope in our hearts’. ‘It couldn’t get better’, thought Damian Kavanagh, then a 20-year-old insurance worker, on his way to his second successive FA Cup semi-final, at the same ground, with the same opponents and Liverpool once again wearing red. As Martin Thompson, a 19-year-old then working in a food factory, poignantly observes: ‘It was just one of those mornings where you open the curtains and the sun is shining and it just feels good to be alive.’

Many, however, already had forebodings. The Leppings Lane end of the ground, where Liverpool fans were once again to be located, had a long history of severe over-crowding. Many had experienced it before, and several of those in the book talk of taking precautions to get tickets for the stands if they possibly could in order to avoid the almost certain crush behind the goal. What few could have anticipated was that a police officer with no experience of such events would be put in charge of the match, that the Football Association would fail to make the appropriate safety checks in advance and that the emergency services would be entirely unprepared for a major incident of the type that unfolded that afternoon. In fact, in many respects those in charge – the football club, the police service and others – knew very well that there were considerable risks. As Stephen Wright, then a 20-year-old plumber, puts it, they were ‘playing Russian roulette’ with the fans’ lives. But in the main they didn’t care. As Jegsy Dodd, a 31-year-old musician at the time, rightly observes, ‘football fans were treated like animals in those days anyway’.

What then unfolds – even to those like me who know a fair bit about Hillsborough – is almost unrelentingly shocking. The fans ripping down hoardings to use as makeshift stretchers, using whatever first aid they knew and attempting elementary triage in order to get help to those most likely to benefit, whilst police officers stood helplessly to one side, or worse, continued to behave with extraordinary antagonism toward fans they saw as nothing more than trouble-makers.

The accounts of the agonising searches by friends and relatives for those with whom they travelled to the match but had lost contact are hard to read. The dawning realisation in some cases that they would never see their child, their sibling, their friend alive again, though it can be anticipated by the reader, remains heartbreakingly powerful. The extraordinary conduct of the police as the cover-up that would seek to blame everything on drunken fans quickly gathers pace is sickening.

Barry Devonside, father of Chris who died that afternoon, talks of being approached by police officers immediately after identifying his son and confirming his address and date of birth. Their first words: ‘Mr Devonside – could you tell us how you got to Sheffield today? Did you stop for a meal, or have a drink?’ Likewise Martin Thompson, only 19 at the time, who had just found the body of his brother Stuart in the gymnasium being used as a temporary mortuary:

Two coppers came over and sat me down. That part of the gym was laid out like a school exam hall – there were rows of tables like exam desks. They sat me down at one of these desks and said they needed to take a statement from me. There was no sensitivity about the way they spoke to you, no ‘Do you want to take a few minutes to collect yourself?’ or anything like that. It was straight into it – they slapped this sheet down and looked at me and said, ‘What have you been drinking?’

From early that Saturday evening, the conspiracy grew. Here, some of the most compelling testimony comes from Dr John Ashton, a medic then working at Liverpool University. He had worked valiantly on the pitch and elsewhere trying to save lives and to provide some form of organisation to the rescue attempts that the emergency services so signally failed to offer. Arriving back in Merseyside late at night, he immediately went on the offensive, taking to the airwaves, attempting to ensure that the truth of what had happened that afternoon became known. By Monday, Yorkshire’s Regional Medical Officer was on the phone warning him off, and behind the scenes, letters from and to NHS top brass, senior government figures and even the Royal Family were carefully creating the impression that the response of the emergency services was exemplary. Ashton knew better and never tired of telling people so.

Ashton was far from alone in coming under pressure to drop it all. Families and campaigners knew full well that their phones were tapped. Some were followed by plain clothes officers, others were openly threatened. One was assaulted by a police officer in front of a serving chief constable. The campaign to discredit everyone linked with the families’ campaign was tenacious, unrelenting and, it seems, went to the very top.

For over a quarter of a century, the Hillsborough Family Support Group, and the Hillsborough Justice Campaign that emerged later, had to battle to remove the stigma that had been so unfairly attached to those that died and to get a semblance of justice. Of course, many helped them, and all that did so deserve enormous credit. But, in the end, this is not a story about the big names but about the ordinary folk of Merseyside who prevailed, and prevailed against all the odds.

Hillsborough Voices is an extraordinarily powerful account of this most scandalous of stories. It is important on any number of levels. First and foremost, it gives us the opportunity to hear those voices that the authorities wanted for so long to drown out. As such, it can be added to the report of the Hillsborough Independent Panel and other documents in finally allowing the truth to be known. As Andy Burnham quite rightly observes:

establishing the full truth about Hillsborough is not just vital for the people who suffered directly, it fills the missing pages of the social history of our country […] It tells us how we were governed and policed in the second half of the twentieth century.

Indeed. It tells us that we were governed and policed by an elite that cared little for the lives of ordinary folk. It tells us that those that governed us cared little for truth and less still for justice. It is frightening how easy it was for those in power to close ranks and turn their backs. Nevertheless, the Hillsborough campaign has also shown what can be achieved in a democracy, even one in which the cards are so heavily stacked. One must now hope that the example of the Hillsborough campaigners, and the model of the independent inquiry established in this case, will be applied elsewhere where it is believed that major miscarriages of justice have occurred. Orgreave and the miners’ strike of 1984-85 would be a good start.

Tim Newburn is Professor of Criminology & Social Policy at the LSE and author (with Rogan Taylor and Andrew Ward) of The Day of the Hillsborough Disaster: A Narrative Account (Liverpool University Press, 1995).

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

1 Comments