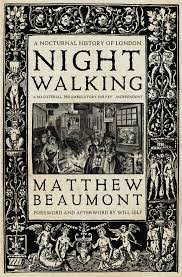

Nightwalking: A Nocturnal History of London offers a literary portrait of nighttime London, the writers who have wandered the city after sunset and the people they encountered on their walks. Matthew Beaumont offers an alternative account of the city streets through the prism of its historical ‘nightwalkers’, uncovering hidden topographies of nocturnal London. This is an excellent book offering a wealth of research conveyed with passion, finds Penny Montague.

Nightwalking: A Nocturnal History of London. Matthew Beaumont. Verso. 2015.

In nocte veritas; in night, truth. London’s nocturnal face is an unmasking of its diurnal façade. When one thinks of the London night in the present age, iconic images of Westminster, Piccadilly and the Thames Skyline are usually the first to emerge. The illuminations that we take for granted today are, of course, a modern innovation; in centuries past, traversing the streets of London at night was a perilous undertaking. London has been the home and muse of many writers over the last millennia, and its nocturnal thrills provide an artistic stimulus distinct from its daytime charms. In Nightwalking, Matthew Beaumont, co-director of the UCL Urban Laboratory, has written an ambitious and erudite sequel to his co-edited Restless Cities (2010), presenting the London night as a historical and literary phenomenon from the medieval period into the Victorian era.

In nocte veritas; in night, truth. London’s nocturnal face is an unmasking of its diurnal façade. When one thinks of the London night in the present age, iconic images of Westminster, Piccadilly and the Thames Skyline are usually the first to emerge. The illuminations that we take for granted today are, of course, a modern innovation; in centuries past, traversing the streets of London at night was a perilous undertaking. London has been the home and muse of many writers over the last millennia, and its nocturnal thrills provide an artistic stimulus distinct from its daytime charms. In Nightwalking, Matthew Beaumont, co-director of the UCL Urban Laboratory, has written an ambitious and erudite sequel to his co-edited Restless Cities (2010), presenting the London night as a historical and literary phenomenon from the medieval period into the Victorian era.

‘The day is for honest men, the night for thieves’ (Euripides). The belief that nightwalking was a precursor to deviancy precipitated the establishment of laws against nightwalking in England in 1285, aiming to reduce rising crime levels in town and cities, to regulate the lives of the general public and to restrict the movements of itinerants and vagrants. Announced by the ringing of church bells, the London curfew required the closing of the city gates from sunset to sunrise and the arrest by the city’s watchmen of those found on the streets after dark without sufficient justification. However, in actuality, the criminalisation of nightwalking was only applied to the poor and homeless, whilst the prosperous were free to walk the dark streets at will.

Beyond the first two chapters, the majority of the book tends to focus on nightwalkers from the upper end of the social scale, who are referred to as ‘noctambulants’: those nightwalkers whose pedestrianism was of an optional, rather than necessary, nature. The unemployed (or underemployed), referred to as ‘noctivagants’, are equivalent to Karl Marx’s lumpenproletariat: an underclass subsisting at the edges of industrial society. However, these divisions were not always unambiguous, creating a liminal space in which the different classes could intermingle and consume the unique offerings of the night. The relationship between these classes may be seen as symbiotic or mutually predatory. Indeed, the etymology of the terms ‘noctivagant’ and ‘vagrant’ hints at the notion of straying beyond established boundaries, and the night watchmen who were charged with protecting the city were often corrupt.

Image Credit: St Pauls Stairs (Davide D’Amico CC2.0)

Image Credit: St Pauls Stairs (Davide D’Amico CC2.0)

In addition to the differing treatments of rich and poor Londoners for whom night-time conditions were distinctly different, Nightwalking also reveals the divisions between the perceived activities of each gender. Female nightwalkers were regarded as either ‘streetwalkers’ or potential victims of predatory men. In fact, the term ‘common nightwalker’ had become synonymous with ‘prostitute’ by the eighteenth century, whilst male vagrants were chiefly categorised as ‘idlers and vagabonds’ (37). Although there are some fleeting descriptions of the female experience of nocturnal vagrancy, they are frequently filtered through the perceptions of the featured male writers, including Samuel Johnson’s articles about the prostitute Misella; William Wordworth’s poem about a ‘Female Vagrant’ and Thomas De Quincey’s apparent attachment to Ann, a fifteen-year-old prostitute. The brief mentions of figures such as Mary Young, a celebrated prostitute-turned-thief who was executed for her crimes against property, call for further exposition. Beaumont discusses The Midnight Ramble (157-61), an eighteenth-century story by an anonymous author (presumed male) of a pair of upper-class women who disguise themselves as monks in order to explore the streets of London at night; yet he does not mention that it shares several superficial similarities with Aphra Behn’s The Feigned Courtesans; or A Night’s Intrigue. In the latter narrative, written a century earlier, the female protagonists also use the concealment of night to overcome the restrictions of their class, albeit by disguising themselves as courtesans. As a political spy and popular dramatist of her time, Behn might have been an intriguing addition to this discussion of night-inspired writing and writers.

One of the strengths of Nightwalking is the way in which it uncovers the hidden historic topographies of London that lie beneath our cement-laden streets. As Beaumont argues, the night obscures the visual realm that distracts from the subterranean realities of the land. In a similar manner, Nightwalking uncovers the forgotten landmarks of London and unravels the urban transformations undergone over the centuries. For instance, Marble Arch now stands on the site where up to 60,000 public hangings were undertaken over a six-hundred-year period. The busy modern thoroughfare of Oxford Street was once the Tyburn Road, on which thousands of spectators would congregate in order to watch the latest mass execution at the Tyburn Tree.

Furthermore, the third chapter, ‘Affairs that Walk at Midnight: Shakespeare, Dekker & Co’, was a particular joy for this reviewer as it bridges the historical and the literary realms whilst also exploring the ways in which Shakespeare’s characters ‘[seek or exploit] the protection of darkness’ (74) in several plays, including Macbeth, Julius Caesar and King Lear. Another highlight was the final two chapters, which reveal that Charles Dickens’s frequent night walks were an essential aspect of his writing method (in an apparently similar way to Haruki Murakami’s use of long-distance running to sustain his writing). It was also fascinating to discover the interactions between Dickens’s night-long wanders and his fictional writing, such as the lengthy walk between Kent and central London undertaken by Pip in Great Expectations. However, as a text that appears to champion the act of aimless wandering over the direct navigation between two points, the central section of the book does appear to suffer from some meandering repetitiveness, although there are still moments of brilliance within those middle chapters.

In conclusion, Nightwalking is an excellent addition to the burgeoning field of psychogeography as well as the established domains of literary criticism and historical narrative. The main text is sandwiched between a foreword and afterword written by Will Self, prominent writer and psychogeographer, but this celebrity endorsement is hardly necessary due to the wealth of research and passion conveyed within the pages of the book. Beaumont comments that in the title of Dickens’s ‘Night Walks’, ‘night’ might be read as either an adjective or a noun. Similarly, this book’s own title and Beaumont’s discussion personify the night as it haunts London in perpetuity.

Penny Montague completed an MA in Literary Linguistics (with distinction) at the University of Nottingham in 2015 and graduated from The Open University with a first-class BA Honours in English Language and Literature. She tweets at @pjmontague. Read more by Penny Montague.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Very interesting!