In Veiled Threats: Representing the Muslim Woman in Public Policy Discourses, Naaz Rashid explores how Muslim women are represented in UK policy discourse, with a particular focus on critically examining and challenging the aims of counter-terrorism initiatives that purport to empower Muslim women. Maria W. Norris welcomes this as a vital, timely study that should be required reading for scholars of counter-terrorism policy, nationalism and feminism as well as policymakers involved in reviewing and implementing these policies.

Veiled Threats: Representing the Muslim Woman in Public Policy Discourses. Naaz Rashid. Policy Press. 2016.

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

Muslim women – their bodies, their choices, their clothes – are never far from the Western imagination. Several European countries have recently banned the burqa, and this summer fifteen towns in France also banned the burkini, the swimsuit favoured by some Muslim women. French Prime Minister Manuel Valls backed the move, stating that the burkini ‘symbolizes the enslavement of women’. David Lisnard, the Mayor of Cannes, the first town to ban the burkini, has claimed they are symbols of Islamic extremism. Striking photos of four armed officers forcing a Muslim woman to undress in Nice have astonished the world. The woman was also issued with a fine ticket, which said that her outfit was not ‘respecting of good morals and secularism’. Whilst most of the bans have now been overturned, the summer was a stark reminder of the power governments have to regulate women’s behaviour.

Muslim women – their bodies, their choices, their clothes – are never far from the Western imagination. Several European countries have recently banned the burqa, and this summer fifteen towns in France also banned the burkini, the swimsuit favoured by some Muslim women. French Prime Minister Manuel Valls backed the move, stating that the burkini ‘symbolizes the enslavement of women’. David Lisnard, the Mayor of Cannes, the first town to ban the burkini, has claimed they are symbols of Islamic extremism. Striking photos of four armed officers forcing a Muslim woman to undress in Nice have astonished the world. The woman was also issued with a fine ticket, which said that her outfit was not ‘respecting of good morals and secularism’. Whilst most of the bans have now been overturned, the summer was a stark reminder of the power governments have to regulate women’s behaviour.

In this climate, Naaz Rashid’s Veiled Threats: Representing the Muslim Woman in Public Policy Discourses is a timely and crucial read. The book provides vital discussion of the gendered aspect of counter-terrorism. Focusing on counter-terrorism initiatives that seek to empower Muslim women, it begins with a vital question: ‘How is the empowerment of Muslim women causally related, or even connected, to preventing violent extremism?’

This answer is explored over the course of nine chapters, including a prologue and an epilogue. These chapters flow from each other, exposing different angles of the problem. Rashid writes in a clear and authoritative style from the outset, showcasing the many ways that projects that seek to empower Muslim women often have the counter-productive effect of removing their agency.

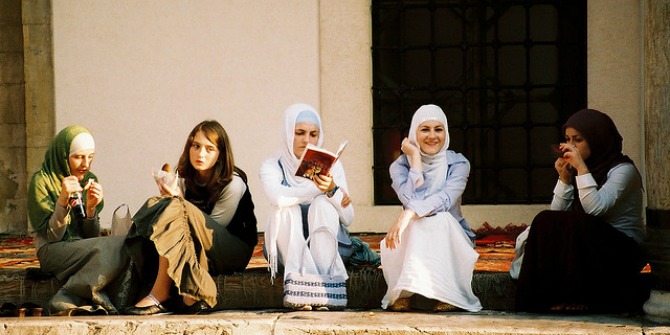

Image Credit: Crop of ‘The Face of Terror…or what you can be easily led to believe’ by Steve Snodgrass licensed under CC BY 2.0

Image Credit: Crop of ‘The Face of Terror…or what you can be easily led to believe’ by Steve Snodgrass licensed under CC BY 2.0

In particular, Rashid focuses on the way ‘in which Muslim women are seen solely in relation to their religious affiliation. This is based on Orientalist stereotypes of the uniquely misogynist Muslim man, inflected with contemporary representations of problematic Islamic masculinity in the post 9/11 world’ (162). In this context, she argues that policy initiatives geared towards empowering Muslim women are ‘part of a broader imperative to define national (and European) borders against a background of racism and post-colonial guilt rather than ‘‘women’s liberation’’ per se’ (5).

The book is at its most valuable when it deconstructs how the feminist rhetoric of empowerment and personal freedom has been co-opted as a civilising mission in counter-terrorism policy. Through Chapters One to Three, Rashid evaluates the Prevent programme and its endorsement of Samuel Huntington’s ‘Clash of Civilisations’ theory. The Prevent programme is the branch of UK counter-terrorism concerned with stopping people from becoming terrorists. It has grown from a modest proposal in 2006 to effectively becoming law in 2015. For years, Prevent has framed Muslim communities as being at best passive about, and at worst complicit with, extremism. Rashid deftly compares the Prevent programme to an immunisation programme: ‘Once the backward and barbaric practices are treated and the community modernised, partially through the ‘‘empowerment’’ of women, then it will be resilient from the disease of radicalism’ (161).

The same civilisational drive is present when discussing how feminism works in the context of UK counter-terrorism strategy. Rashid argues that it is part of a ‘civilisationist discourse in which it is positioned as part of a modernising mission. This perspective claims ownership of and responsibility for feminism as a Western value, thus ignoring a whole history of black feminist critiques of white feminism and also the existence of ‘‘native feminisms’’’ (10).

The book’s policy analysis is augmented by interviews with Muslim women who were involved with or affected by projects to empower Muslim women. This is a particular strength of Chapter Five, which analyses the role of motherhood present in counter-terrorism policy. Rashid points out how counter-terrorism’s concern with Muslim families is rooted in imperial constructions of pathologised, ‘Othered’ families, with violent fathers and sons and submissive mothers and daughters. Most of Chapter Five is dominated by an analysis of the role models roadshow that was held with the goal of addressing the low levels of economic activity among Muslim women. Rashid explains how the roadshow is embedded in a neoliberal discourse that has appropriated feminist language. The focus of the roadshows was on Muslim women as mothers ensuring their daughters’ academic success through sufficiently high aspirations. Here, structural inequalities that Muslim women may experience as a result of the socioeconomic position related to their citizenship status is not seen as something that needs to be dealt with.

The answer to the question of how Muslim women have become connected with counter-terrorism policy thus lies in how these very policies have refused to see women as agents. This, in turn, makes Muslim women – and their sartorial choices – barometers of both integration and extremism, representing what is acceptable and what is deviant in British society. As Rashid concludes:

Policy focused on ‘‘Muslim women’’ collated together all women who are Muslim, a disparate and multiply-differentiated group and de facto attributed any problematic issues to religious affiliation. As well as perpetuating anti-Muslim rhetoric, such policy discourses, focused on religious affiliation alone, also obscure continuities with earlier racisms as well as other axes of social division in society, such as class and regional inequalities which also affect non-Muslims (175).

Recently, The New York Times has claimed that radicalised women are now playing an active role in planning and executing terrorist attacks in Europe. This ensures that European countries will redouble their focus on Muslim women. As such, Rashid’s book should be required reading not only to academics researching counter-terrorism policy, nationalism and feminism, but also to policymakers tasked with reviewing and implementing such policies in Europe. The Prevent programme remains the flagship UK counter-terrorism policy, and Rashid’s book is a stern warning to policymakers of how problematic it is when security policy approaches identity in a reductive way.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.