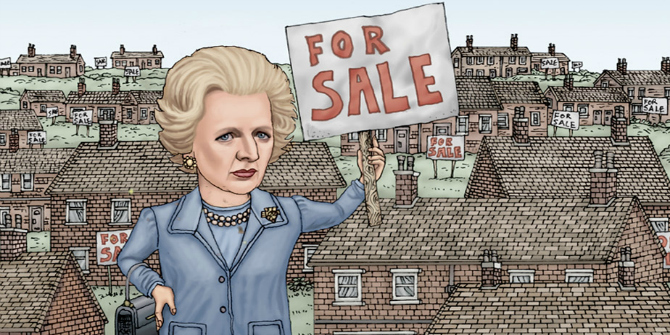

In Culture, Economy and Politics: The Case of New Labour, David Hesmondhalgh, Kate Oakley, David Lee and Melissa Nisbett focus on the emergence of cultural policy as a key concern under the Labour party between 1997 and 2010. Drawing particularly upon interviews with key figures, this is a valuable, even-handed book that is recommended reading for any course exploring UK culture and politics post-Thatcher, writes Jonathan Vickery.

Culture, Economy and Politics: The Case of New Labour. David Hesmondhalgh, Kate Oakley, David Lee and Melissa Nisbett. Palgrave Macmillan. 2016.

The spectre of New Labour returned on 6 July 2016, on the publication of The Iraq Inquiry Report. Interviewed by BBC News on the occasion, Lord Butler (former Cabinet Secretary) remarked that ‘New Labour was a small cell inside the Labour Party, and a small cell inside the government’ (1). The sudden reappearance of New Labour architect and leader Tony Blair on international news was also a sober reminder of the complex role of political rhetoric in New Labour’s self-representation and ways of communicating policy. What mysteries endure about New Labour often pertain to the initial emergence and implementation of new policies (often referred to as ‘initiatives’) – a process that was mediated by a micro-managed press delivery of rhetorical flourish as much as informal and personality-driven priorities. As Diane Abbott remarked during the same round of interviews: there was no cabinet government under Tony Blair.

The spectre of New Labour returned on 6 July 2016, on the publication of The Iraq Inquiry Report. Interviewed by BBC News on the occasion, Lord Butler (former Cabinet Secretary) remarked that ‘New Labour was a small cell inside the Labour Party, and a small cell inside the government’ (1). The sudden reappearance of New Labour architect and leader Tony Blair on international news was also a sober reminder of the complex role of political rhetoric in New Labour’s self-representation and ways of communicating policy. What mysteries endure about New Labour often pertain to the initial emergence and implementation of new policies (often referred to as ‘initiatives’) – a process that was mediated by a micro-managed press delivery of rhetorical flourish as much as informal and personality-driven priorities. As Diane Abbott remarked during the same round of interviews: there was no cabinet government under Tony Blair.

Among the many books on the New Labour period, Culture, Economy and Politics: The Case of New Labour is different insofar as it avoids the tangle of political rhetoric and personality, the inter-departmental territorialisation and the factional ‘project’ of the New Labour ‘cell’. It rather attempts to charter the originary stages in the formulation and implementation of a certain species of policy – ‘cultural policy’ (although New Labour rarely used that term). So, the book asks: aside from the transformation of Labour political discourse through the rhetoric of communitarianism, ‘the stakeholder society’, the Third Way, Blair’s Christian Distributism and so on and on, why and how did policies for the arts and culture become (apparently) so important under the New Labour government (1997-2010)? Bear in mind that the political reasons for our habitual conflation of ‘New Labour’ and ‘Government’ remain outside the parameters of this book.

Replacing the Department of National Heritage (1992-97), the Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) became symbolic of the new economic landscape of innovation and creativity, technology and fast-globalising media industries. ‘Creative industries’ is now a commonplace term because of New Labour and the fundamental innovations it affected in public policies for just about everything else (except its few and notorious areas of neglect – transportation, manufacturing and heavy industry among them). This book, based on a funded collaborative research project, attempts a historical-critical overview of the policy innovations in arts and culture, specifically framed so as to register the politically-engineered interconnections of culture, economy and new organisations (such as NESTA). Unsurprisingly, the most effective research method for such a task is the in-depth interview, here conducted with 45 key individuals and used in both narrative and quotation.

Image Credit: Department of Culture, Media and Sport (Howard Lake CC BY SA 2.0)

Image Credit: Department of Culture, Media and Sport (Howard Lake CC BY SA 2.0)

New Labour’s aims were often clear enough, but the origin and sudden implementation of policies betray a tangle of intriguing rationales. The book frames its investigation around the broad concerns of historical social democracy to which, one assumes, New Labour must be understood in direct relation. The book does well to delineate the political and institutional contexts within which policy emerged, and then to show how the usual lobbying, agenda-setting and deliberations that accompany policy formation took somewhat unpredictable forms throughout the New Labour epoch. While more recent theories of networks or governance go some way towards explaining New Labour’s policy complexity, this study is assiduously tied to its empirical content and determined to provide an open and frank narrative account of the ideological shifts on the level of values, party allegiance and national identity. If the book fails, it is only to underscore just how – like the Iraq war – the consequences of New Labour are still all around us.

The book opens with two very informative chapters, ‘Culture, Politics and Equality: The Challenge for Social Democracy’ and ‘New Labour, Culture and Creativity’, both of which set out the conceptual issues and a brief mapping of the actors and agencies involved in the New Labour policy phenomenon. Blair’s ‘Cool Britannia’ has to get a mention, even though there’s not a great deal to say about it; more interesting is the rise of ‘creativity’ as a policy concept, the explosion of new policy ideas for generating social value, central of which was the ‘creative industries’, animated by Chris Smith and the new DCMS, Lord (David) Puttnam, John Newbigin and others. It was not until the 2000s that real policy and dependable funding began for the arts and cultural sector; but with the flow of funds came a radically new modus operandi of professional administration, monitoring and measurement, rationalisation and reporting, outlined by a very good Chapter Three, ‘The Arts: Access, Excellence and Instrumentalism’.

Apart from the stuff of public policy – funding systems, the National Lottery and so on – the book also offers useful accounts of film policy, the sudden importance of copyright and IP, the new frontiers of the digital as well as more traditional Labour issues, such as the settlement for the regions, urban development and the inclusion of ‘the people’ (increasingly segmented in a new market framework of identity politics and minority interest groups). Heritage is a relatively discrete subject in the book, whose chapter concludes with the salutary statement: ‘The story of heritage under New Labour demonstrates the fundamental point that much about culture happens independently of public policy’ (183).

The book opens with admirable aspirations – ‘a sociology of policy that recognises complexity, contingency and power […] the viable goals of cultural policy in a modern democratic society’ (15). New Labour effectively reinvented historic social democracy, but in ways so complex and compromised (in relation to so-called neoliberalism) that the book really required a lot more critical theory to make full political sense of its very valuable empirical content (with regards to this as an argument yet to fully unfold, see also David Hesmondhalgh et al 2014 and Bob Jessop 2007). The financial disaster of the Millennium Dome, university fees, decreasing free speech on campuses, mass surveillance, the routine banning of artists and musicians from the country because of their political incorrectness and so on, furthermore all remain outside the main focal points of this book. Also outside is the failure of New Labour to support the 2003 UN Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage as well as its odd lack of enthusiasm for the 2005 UN Convention on Cultural Diversity, particularly in the face of what is surely New Labour’s greatest cultural policy legacy: multiculturalism and the integration of identity politics into every area of public service provision.

Nonetheless, this is a very valuable book, in part as it fills a huge gap in the research. It attempts to be even-handed, at once supporting the earnest social democratic aspirations of New Labour’s ‘heroic’ years, but also identifying its failings – ultimate failings as far as cultural policy is concerned. Depending on what you take cultural policy to be – whether policy is indeed the intervention of government for the public good and not the imposition of political will on an otherwise autonomous public realm – it became a multiplicity of things with New Labour, and we would need another book entirely to explore the fate of what was once called ‘public’ culture. One cannot deny the huge public subsidy New Labour engineered for the arts, museums and galleries and heritage (including their financially strategic use of the once-controversial mechanism of the National Lottery). But, at the same time, the attenuation of cultural autonomy and institutional self-determination under New Labour, was, in places, extreme. In all, this book covers a huge territory as it is, and given its achievement in presenting a series of complex situations with admirable clarity, it should become a core text on any reading list relating to UK culture and politics since Thatcher.

Dr. Jonathan Vickery is an Associate Professor in Warwick University’s Centre for Cultural Policy Studies. He is Director of the Masters programme in Arts, Enterprise and Development, and is currently involved in research projects on global cultural policies, the impacts of European cultural industries and creative industries in Shanghai. Read more reviews by Jonathan Vickery.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

1 Comments