What has been the impact of digital technologies on the development of today’s youth? And how has the digital world changed the way we see ourselves and relate to each other? In Ctrl Alt Delete: How I Grew Up Online, blogger, author and digital consultant Emma Gannon shares her experiences of coming of age, living and working in the digital era. Gannon enfolds illuminating facts and figures into her engaging and relatable personal memoir to examine both the risks and opportunities afforded by digital technologies, writes Emma Wilson.

Emma Gannon spoke alongside Rachel Coldicutt and Deana Puccio as part of the LSE Space for Thought Literary Festival 2017. ‘Growing Up Online: A Digital Revolution?’ explored the risks and benefits for young people growing up in cyberspace – listen to a recording here.

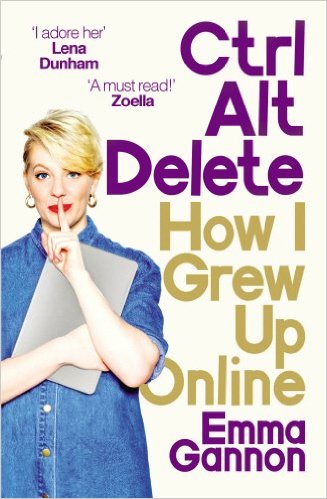

Ctrl Alt Delete: How I Grew Up Online. Emma Gannon. Ebury Press. 2016.

Digital technology has revolutionised the ways we navigate through life. We are living in an ever-connected world that has fuelled a perpetual quest for knowledge acquisition. An entire generation has now grown up with the Internet and Emma Gannon is one of these individuals. Writing in an autobiographical style, the author, born in 1989, shares her account of living and working under a digital spotlight.

Digital technology has revolutionised the ways we navigate through life. We are living in an ever-connected world that has fuelled a perpetual quest for knowledge acquisition. An entire generation has now grown up with the Internet and Emma Gannon is one of these individuals. Writing in an autobiographical style, the author, born in 1989, shares her account of living and working under a digital spotlight.

Ctrl Alt Delete: How I Grew Up Online is written from the perspective of a young British woman living in the internet age, with a good integration of facts and figures to support her arguments. The book is both a personal memoir and a piece of discourse that encourages debate. As a fellow British-born millennial with an affinity to Twitter, I found the book very relatable. From becoming a professional at airbrushed selfies to forming a digital identity through social networking sites, the forthright and matter-of-fact way in which Emma delivers anecdotes from her life makes the book highly engaging from the start. Such personal insight enables the reader to feel more connected to the author. Most of all, I appreciated how the author finds a balance between discussing the risks of technology and highlighting the opportunities it can present to future generations.

Ultimately, Ctrl Alt Delete seeks to explore how technology and the Internet is forming and developing our social identity: ‘Everyone is looking at everyone else’s feeds to try to work out what the truth is about other people’s lives, but mainly worrying about creating their own online identity’ (81). Such a phenomenon has only developed over the past decade or so, mainly with the proliferation of social networking sites. Within this book, the author focuses her discussion on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.

Digital technology enables us to manipulate how we are perceived and the way in which we perceive others, and has an impact on our self-esteem, sense of worth and relationships with those around us. To illustrate these points, the author recounts the particular impact of online communications in her romantic encounters:

I clued myself up using online music forums and I could tell he was impressed. This soon started to become an obsession, faking my interests to grab his attention and affection […] I could also begin to easily fake things – and by things, I mean myself: my own personality (68).

Physical appearance can also be manipulated. In Chapter One, ‘Photoshopping Myself’, Gannon describes, at the age of 13, her endless obsession with editing photographs of herself: ‘I became more and more transfixed on making my online self look a certain way. By a ‘‘certain way’’ I mean more desirable in the context of what I thought society wanted. It started with the airbrushing of my face, the brightening of my eyes, the saturation of my skin’ (15).

I found this chapter particularly relevant to the pressures faced by today’s generation of young people. Although size zero models and airbrushing techniques are not new, technology has created an environment in which we are hounded by a constant stream of unobtainable perfection. With the press of a button via an app on our smartphones or through launching an extra tab on our computer’s web browser, we can immerse ourselves in the lives of total strangers. We can follow, in real-time, the most popular ‘trends’ on Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr. From hashtags that glamorise self-harm and anorexia to online abuse towards feminists and minority groups, the author is justified in voicing her concerns with social media. By addressing topics such as body image and online bullying – or ‘trolling’ – the author highlights some of the issues that policymakers are struggling to address. Without an ‘Internet Police’, what can be done to protect people when they go online?

Image Credit: (Pixabay CCO)

Image Credit: (Pixabay CCO)

Despite the dangers posed by living in an ever-connected world, the author also presents a sense of optimism. The digital world can, in fact, be a force of good: from encouraging entrepreneurialism to providing marginalised groups with a platform to get their voices heard. Gannon spends much of the second half of the book presenting some of the opportunities afforded by technology: ‘The Internet allows a new kind of freedom where we don’t need to work the same nine-to-five office jobs any more because we are more connected than ever’ (172).

In Chapter Nine, the author describes the changing landscape in the context of employment. She cites two interesting statistics: 1) by the year 2020, 40 per cent of the workforce will consist of freelancers and independent consultants (174) (Source: Intuit); and 2) in a 2015 survey of 2,348 people aged 18-25, the most popular career choice was to become a ‘blogger’ (183).

Technology is not simply about structural change. We are, in fact, witnessing a shift in attitudes, behaviours and personal preferences within society. Millennials are beginning to rebel against the status quo. According to the author, jobs-for-life are becoming less desirable and the Internet has ‘killed hierarchy’ (174). Today’s generation are far more restless and agitated with the state of the world, and technology provides a platform to voice discontent and strive towards change.

Most significantly, the variety of jobs has diversified, creating a space for start-up companies and web-based business. In 2016, 70 per cent of marketers reported increased spending on social media, and 55,000 people have the term ‘influencer’ in their LinkedIn job titles (160). This poses an important question for the education sector: given the increased importance that employers are placing upon digital competencies, should there be a modification of the curriculum and the styles in which learning takes place? Should technology play a more integrated role in the classroom? The points made in Chapter Eight present a very convincing argument for such change.

Finally, the author discusses how social media has created ‘a new kind of democracy’ and provides a platform for ‘everyone to have a voice’ (233). Emma focuses her commentary on the rise in online feminist movements such as #HeForShe, #AskHerMore, #LikeAGirl and #EverydaySexism. The opportunity to build global communities and campaign for change is, ultimately, one of the great successes of social media.

Overall, Emma’s first publication provides some very interesting insights into the impact of technology on today’s generation – particularly young women in British society. Looking ahead, I would be keen to read about and compare the experiences of individuals from other nationalities, genders and ethnicities. It would also be interesting to further discuss some of the reasons behind a shift away from the jobs-for-life employment market. Could it be a change in personal preferences or an unwanted consequence of job insecurity in the labour market? Given the increase in fixed-term and temporary employment, zero-hours contracts and unpaid internships, these are important considerations that must be addressed.

To conclude, Ctrl Alt Delete: How I Grew Up Online provides confirmation that we are living in an increasingly connected and digitised world. A holistic understanding of the online environment will, ultimately, help direct future policy. In turn, this will help us to address current challenges and capitalise upon the many opportunities afforded by digital technologies.

Emma Wilson is an alumna of LSE with a background in mental health research, policy and communications. She is currently working as Research and Evaluation Graduate Intern within the Learning Technology and Innovation team at LSE. Her main areas of interest are the mental health of children and young people, and the impact of the digital world in today’s society. The topic of her Masters thesis focused on the role of technology in the design and delivery of supporting young people with anxiety and/or depression. Emma can be found on Twitter (@MindfulEm), where she actively promotes news stories that address matters of health, education and digital policy.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.