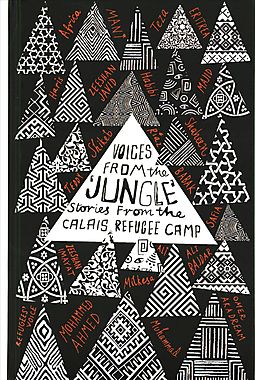

Voices from the ‘Jungle’: Stories from the Calais Refugee Camp offers a collection of individual testimonies written by a number of people residing in the so-termed Calais ‘Jungle’, the refugee camp in Northern France. While more accounts from women would have been welcome, this is a moving and timely anthology that seeks to give a voice to the lives, experiences and future hopes of those living in the camp, writes Sharon Wu.

Voices from the ‘Jungle’: Stories from the Calais Refugee Camp. Marie Godin, Katrine Møller Hansen, Aura Lounasmaa, Corinne Squire and Tahir Zaman (eds). Pluto Press. 2017.

In a political climate where refugees are often used as pawns in a global geopolitical game, Voices from the ‘Jungle’: Stories from the Calais Refugee Camp humanises those who suffer most from the current ‘refugee crisis’. Voices from the ‘Jungle’ is a collection of first-hand narratives gathered from the ‘Jungle’: the infamous Calais refugee camp located in the north of France. Although refugees seeking passage to the UK have set up informal camps around Calais for almost two decades, the Calais ‘Jungle’ in its largest and most recognised form existed from January 2015 until October 2016, when French officials evicted the camp. With the help of various humanitarian groups and volunteers, residents of the ‘Jungle’ established sanitation systems, restaurants, a library, healthcare facilities, educational services and all types of creative and artistic endeavours. They had arrived from all over the world, including Syria, Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan and Afghanistan, spending anywhere from a few days to a few months at Calais.

In a political climate where refugees are often used as pawns in a global geopolitical game, Voices from the ‘Jungle’: Stories from the Calais Refugee Camp humanises those who suffer most from the current ‘refugee crisis’. Voices from the ‘Jungle’ is a collection of first-hand narratives gathered from the ‘Jungle’: the infamous Calais refugee camp located in the north of France. Although refugees seeking passage to the UK have set up informal camps around Calais for almost two decades, the Calais ‘Jungle’ in its largest and most recognised form existed from January 2015 until October 2016, when French officials evicted the camp. With the help of various humanitarian groups and volunteers, residents of the ‘Jungle’ established sanitation systems, restaurants, a library, healthcare facilities, educational services and all types of creative and artistic endeavours. They had arrived from all over the world, including Syria, Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan and Afghanistan, spending anywhere from a few days to a few months at Calais.

The stories in this book were originally written for a short accredited undergraduate writing course on ‘Life Stories’ taught by the University of East London (UEL) in Calais in 2015 and 2016 in collaboration with a number of educational associations within the camp. UEL did not initially intend to publish a book from the class, but the students and instructors together decided that they wanted their voices to be heard by a wider audience. 22 refugees who escaped a perilous situation at home and safely arrived in Calais offer their testimonies, written under a mixture of real names and pseudonyms. The book is divided into five chronological chapters that follow their trajectories, beginning at home and ending at Calais, the UK or elsewhere in Europe. These written narratives are also accompanied by the writers’ poetry and photographs of the camp. All the accounts from Voices from the ‘Jungle’ are beautiful, striking and sorrowful in their own ways: they echo common themes of heartache, family, survival, freedom, discrimination and violence.

The first chapter starts at the beginning, with the writers narrating the initial decision to leave home and head towards Europe. They come from various places and circumstances, but all have one thing in common: home is a dangerous place for each of them. In deciding to flee, they leave behind family and friends without really knowing what is ahead.

The second chapter, titled ‘Journeys’, recalls the tortuous voyages between home and Calais. In addition to the infinite number of dangerous obstacles that refugees face in reaching Calais, this section also shows an often forgotten component of this expedition: waiting. Waiting to register at a border, waiting for a boat to reach land, waiting for a smuggler to say go, waiting for a call from a relative in Europe and waiting in many hours-long lines for all types of reasons. Majid (from Iran) writes:

This was so familiar to us now: Wait, wait, queue, and queue. Midnight came. They gave us tuna fish, bread, coffee, tea, and told us to sleep on the camp beds — and wait (92).

Image Credit: (malachybrowne CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: (malachybrowne CC BY 2.0)

Both the second chapter and the fourth chapter, ‘Living in and Leaving the “Jungle”’, explore the robust informal economy of smugglers who profit from providing safe passage. Smugglers are instrumental in assisting refugees in both reaching Calais and leaving it for the UK or elsewhere. With their expertise, many smugglers abuse their position of power over refugees. In describing his encounter with smugglers in the Saharan desert, Eritrea (from Eritrea) writes: ‘The smugglers are not good people. They are very cruel people, especially towards the ladies. We saw many evil things happening to the ladies. The smugglers liked to have sex with them. It was against their will; it happened by force. They were very cruel towards them’ (83). With their power, smugglers charge exorbitant prices, cram too many bodies into too small spaces and are often unreliable or unpredictable.

Upon arriving at Calais, refugees are faced with a whole new set of challenges. The chapters on life in the camp illustrate inadequate camp conditions in addition to a brutal police presence. Supplies and personal belongings are stolen from unguarded tents and shipping containers. People befriend each other only to betray them later. Infants are born without sufficient access to healthcare and proper vaccinations. The French police regularly and violently crack down on those trying to escape. However, the writers also discuss the community that develops from this adversity: how people come to help others despite language barriers, cultural differences and a lack of resources.

While a beautiful and timely anthology, Voices from the ‘Jungle’ suffers from an unevenness between individual stories. Each chapter begins with an introductory paragraph for background, and then additional, oftentimes unnecessary, explanatory paragraphs are interspersed throughout. These interrupt the flow of storytelling and often explain themes that don’t require clarification. In doing this, the editors’ voices often overpower those of the refugees’, and ultimately prevent readers from reaching their own conclusions. While this choppiness is most evident in the first chapter, ‘Home’, it does lessen as the book progresses.

As addressed in the book’s introduction, the book also lacks a female perspective, as the majority of students on the writing course were men. Safia (from Afghanistan) is the only female narrator in this collection, and she presents a wholly unique perspective amidst the male voices. While most of the male narratives focus on individual safety and survival, Safia writes about all these issues as well as discussing pregnancy, childcare and women’s health at Calais. In a rare moment of pleasure, Safia describes ‘Beauty Day’ at Calais: “‘Beauty Day’, organised by the Blue Bus, is good. It is good because you can have your nails polished and your eyebrows done. People come for massage, nail-polish, for makeup, everything. One time, someone came and I got my hair done, together with another woman’ (173). She delivers a glimpse into the lives of other women living in the camp as well, illuminating a whole host of daily struggles not mentioned by any of the other writers.

Despite the hardships of residing at Calais, many of the authors speak of the camp eventually feeling like a second home. Muhammad (from Syria) writes: ‘Saying goodbye to the camp is like leaving your home once more […] So many things are left behind. So many friends. So many attempts and too many wishes and too much love’ (206). In a later section, he echoes the same sentiment:

I think no man can enter the ‘‘Jungle’’ and leave it in the same manner, without changing. There were so many friends […] Everyone had their own stories and journeys which are greater than could be written in such pages as these (250).

There is still an enormous amount of uncertainty and instability for refugees if and once they sort out their legal status and settle into their new lives in Europe. Calais is just one of many stepping stones on their path towards a freer life. Voices from the ‘Jungle’ opens up this particular step, giving voice to the many who make this voyage.

Sharon Wu is an MSc candidate in the Conflict Studies program at the London School of Economics. She received her undergraduate degree from New York University and previously worked for an independent publisher in the San Francisco Bay Area. Find her on Twitter at @sharonlxwu. Read more by Sharon Wu.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

1 Comments