In The Violence of Austerity, editors Vickie Cooper and David Whyte bring together contributors to explore the negative impact of austerity upon citizens in the UK, covering such topics as health, education, homelessness, disability and the environment. This is a powerful description of the consequences of austerity policies for the UK’s most vulnerable people, writes Paul Caruana-Galizia, and should be read widely.

The Violence of Austerity. Vickie Cooper and David Whyte (eds). Pluto Press. 2017.

Milton Friedman used to say that you can’t have political freedom without economic freedom. Libertarians have taken up his saying as a mantra. There’s logic in it – taxes directly restrict your economic freedom and fund other government interventions – and rhetoric – it casts politics and government as dependent and redundant. But is it right?

We’ve been building up to an answer since the 2010 election of the Conservative-led coalition government in the United Kingdom. The country’s path to economic recovery, the coalition government argued, isn’t more government spending and intervention. It’s ‘austerity’: a sharp reduction in government spending or, in Libertarian terms, a sharp rise in economic and so political freedom. For context, Local Authority spending per person fell by 23.4 per cent in real terms between 2009 and 2015, and general government spending as a percentage of GDP fell by 11 per cent.

The Violence of Austerity, edited by Vickie Cooper and David Whyte, contains chapters on the relationship – always negative – between the UK’s austerity policies and such areas as health and education outcomes, homelessness, the environment, poverty, disability and even the Northern Ireland Peace Process. The book is varied in its coverage, but it shows one thing clearly: for a lot of people in the UK, austerity has created less economic and political freedom.

In Chapter Four, Jon Burnett and Whyte cover ‘workfare’: the welfare conditionality schemes in which people are made to work without pay to improve their employment prospects or risk losing their entitlement to benefit income. They show us that people in ‘workfare’ are often forced into unsafe, physically draining, unpaid jobs. Complaints about working conditions are met with threats of sanctions. Employers, with the government’s backing, have total coercive power. Every year, over 100,000 people are put onto workfare schemes (65). Every year, over a million sanctions are imposed on them (62).

Robert Knox’s chapter, ‘Legalising the Violence of Austerity’ (Chapter Nineteen), shows us that when a government cuts spending, it doesn’t simply provide fewer services. It compensates for lost revenues with harsher enforcement of existing regulations and the implementation of new ones. Local Authorities, for example, are now faced with declining core funding from the central government, and a legal obligation to balance their budgets. Failure to do so can result in fines, disqualification and even imprisonment, Knox tells us. He concludes: ‘austerity has been accompanied by the extension and intensification of legal frameworks into politics’ (185).

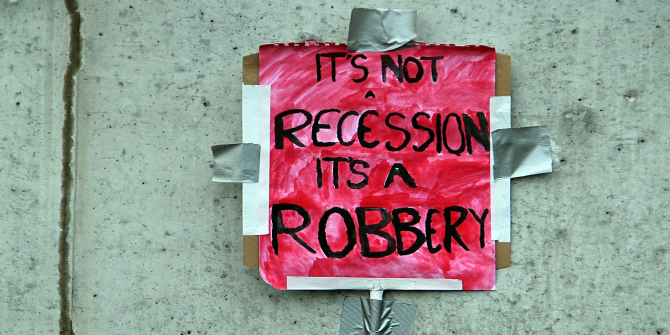

Image Credit: (Funk Dooby CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: (Funk Dooby CC BY 2.0)

A critic might respond: ‘fine, but when funding is limited it must be managed stringently.’ So where is the government making savings? On children, as Joanna Mack shows us in Chapter Seven. Not that there’s room for it: 27 per cent of the UK’s children live in poverty, a higher rate than most EU member states. On taking office in 2010, the coalition government froze the rate of child benefit. On winning the 2015 election, the Conservatives announced further spending cuts, including limiting tax benefits to two children. Lone parent households have experienced the sharpest falls in their incomes over this period (86-87).

Savings are also being made on those with mental illness, as Mary O’Hara shows (Chapter One). Again, not that there’s room for it: mental health services receive 13 per cent of the NHS’s budget while mental illness accounts for 23 per cent of the UK’s total loss of healthy years of life (37). Still, O’Hara writes: ‘mental health provision was hit hard and early by austerity measures and this pattern continued into 2016’ (38).

John Pring tells us that savings are furthermore being made on disabilities (Chapter Three). He quotes an estimate from think tank Demos that disabled people risked losing £28 billion in income support by 2018, in response to then-Conservative Chancellor George Osborne’s ‘emergency budget’ of June 2010 (52). And savings are also being made on those who are homeless, as we see in Chapter Eighteen by Daniel McCulloch. He writes that between 2010 and 2015, the number of people sleeping in rough in England has more than doubled, increasing year-on-year (172). The number has risen by a further 16 per cent from 2015 to 2016. McCulloch cites a study which found that 67 per cent of Local Authorities have seen a rise in rough sleeping as a direct outcome of welfare reforms (173). He also references another that shows that increasingly punitive benefit sanctions exacerbate the risks homeless people face and also the risk of homelessness (173). This is all sad enough to contemplate; sadder still when you see that the savings are a false economy.

The book’s introductory chapter, by Cooper and Whyte, nonetheless misses an opportunity when assessing the success of austerity policy on its own terms. The terms: faster economic growth by cutting fiscal expenditure and public debt, which makes room for private business investment and creates a more competitive economy. Cooper and Whyte argue that austerity was never necessary as UK public debt has been higher; that mainstream economists advised against it; and that Iceland experienced a similar crisis, but didn’t undertake austerity and recovered faster than the UK. The second and third points are fair, the first less so: public debt as a percentage of GDP spiked in 2009 and remains elevated. But this is the most fundamental criticism of austerity policy – a lot of harmful side-effects without the intended effects. We should read more on why this is the case, rather than be told that it just didn’t work.

Cuts in government spending are cuts in total demand, which lower output and raise unemployment. Cuts in government spending in a depressed economy depress that economy even further: they diminish demand when demand is already low. For this reason, an empirical study across a sample of OECD countries by the Peterson Institute for International Economics found no support for the argument that austerity is good for economic growth. Even in purely fiscal terms, austerity is self-defeating: whatever savings are made by, for example, cutting income benefit, are partly offset by lower revenue. There’s only so much fat you can cut before you hit the bone.

Another empirical study by the UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs found that austerity generates income inequality. As Ruth London’s chapter on fuel poverty shows, there are costs to cuts. Fuel poverty, for which the government is scaling back its support, costs the NHS £3.6 million per day (101). The costs are borne by those least able to bear them – children in cold, damp homes fall ill and miss school; adults miss work and lose jobs (Chapter Nine). Those who can afford to heat their homes remain unaffected. There are occasional attempts throughout the book to link austerity and inequality to the Brexit vote. A lot of work has been done on this, and the book feels like it should have had a chapter dedicated to it.

The Violence of Austerity is a powerful description of what’s happening to the UK’s most vulnerable people: more premature deaths, more malnutrition, more suicides, people freezing in their homes. On this basis alone, the book should be read widely. That is, even if you think some of the worrying trends explored in health and in the labour market pre-date austerity policies, the book shows us that a lot more people aren’t economically and politically free, but are suffering and struggling. You’d think they need more, not less, support.

Dr Paul Caruana-Galizia is a Visiting Fellow in the Department of Economic History at the London School of Economics. He is the author of The Economy of Modern Malta and Mediterranean Labor Markets in the First Age of Globalization. He tweets @pcaruanagalizia. Read more by Paul Caruana-Galizia.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Find this book:

Find this book:

2 Comments