In The Greens in British Politics: Protest, Anti-Austerity and the Divided Left, James Dennison draws on statistical data as well as interviews with UK Greens to offer an account of the recent evolution of the Green Party of England and Wales and the Scottish Green Party. While the book suffers from some repetition of content and its findings are somewhat overshadowed by changes in the aftermath of the 2017 General Election, this is still a useful point of departure for future research into the UK Greens, writes Erica Frazier.

The Greens in British Politics: Protest, Anti-Austerity and the Divided Left. James Dennison. Palgrave Pivot. 2016.

The Green Party of England and Wales added 13,000 new members in just one week leading up to the 2015 General Election. In just as little time, the Scottish Green Party saw its membership swell by 600 per cent. What caused this ‘Green Surge’? And where did its momentum go? Why is there now only one Green MP at Westminster?

In his new book, The Greens in British Politics: Protest, Anti-Austerity and the Divided Left, author James Dennison aims to not only follow the recent evolution of the Scottish Green Party and the Green Party of England and Wales, but also to explain the causes and impacts of these changes as well.

The first portion of the book follows a chronological structure, with Chapters Two through Five seeking to establish a narrative of the events leading up to the 2015 General Election. Chapters Six and Seven change their focus by aiming to explain the results of the election by focusing on voters and their constituencies. The book is structured to include keyword lists and abstracts at the beginning of each chapter. It also has a short index at the end for easy access to the most relevant pieces of information. These features are very helpful for readers who wish to glean quick takeaways from each section of the text. Additionally, all chapters incorporate an instructive literature review, which is useful for situating Dennison’s work in context.

Dennison begins his narrative with the results of the 2010 General Election, placing the two Green parties in their relevant political contexts before following the advances they each made. The book also tracks internal changes to party structure, particularly in the case of the English and Welsh Greens, as well as external events such as media coverage and the posturing of other leading political parties. The book draws together quantitative data such as electoral polls, surveys and election results, featuring the kind of statistical analysis so central to research on modern political parties. Dennison’s results are displayed in a number of graphs and tables making the data readily accessible. However, one of the book’s most unique features is the use of qualitative data: specifically, personal interviews with UK Greens. In a field which tends to be so extensively focused on ‘hard’ statistics, these interviews are very welcome.

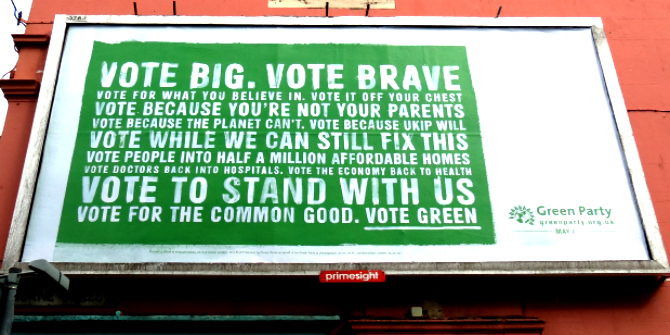

Image Credit: Green Party Billboard (ernie nell CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: Green Party Billboard (ernie nell CC BY 2.0)

In the book’s early chapters, excerpts from the interviews are used to propel the narrative and provide a window into the party’s internal dynamics. For example, Dennison quotes Mark Cridge, Management Coordinator for the party from 2011-15, to lay out the substantial transformation of the party’s online presence. Readers hear from Cridge himself about the once ‘horrific mess’ which became a functional ‘digital strategy’, paving the way for the ‘Green Surge’ (44).

Dennison also uses National Campaigns Director Chris Luffingham’s story of an unexpected bequest to add excitement to the narrative of a small party finding itself with almost dizzying new opportunities (44). Dennison then tempers this promising shift in financial resources and strategy with quotes about the internal tensions stoked by the ‘professionalisation’ of the party. Those in favour of a more centralised approach with a larger staff are contrasted with party members who believe that ‘volunteers’ and grassroots activists are the lifeblood of the party. This structure is a compelling rhetorical device, mimicking the simultaneous rise of the Green Party in the public consciousness and the internal alienation of some of its members.

Unfortunately, these interviews are not incorporated as extensively in the later chapters of the book, dampening the book’s capacity to tell an engaging story. Instead, the book’s final chapters consist of almost exclusively quantitative data, much of which seems to be repeated from earlier in the text and simply supplemented with short bits of new information. Readers might even wonder about the ‘value added’ of some chapters. These features make the text feel as though it is in fact a series of journal articles converted into a book. While the book itself is short, it could have been further streamlined by removing these last few chapters and integrating the information they contain into other portions of the text. Additionally, the prose can be difficult to follow at times. Some sections are rather dry or incorporate unnecessarily dense political science jargon, while others could have benefitted from more thorough editing.

Broadly speaking, The Greens in British Politics does present an instructive body of statistical analyses that highlight the evolution of the Scottish Green Party as well as the Green Party of England and Wales. However, it is possible to argue that, at times, the author may have been too quick to claim causation rather than state that a correlation exists. This is particularly notable in Chapter Six, ‘Who Voted Green and Why?’. Readers might also wonder why the Northern Irish Greens are excluded from the general narrative and statistical analyses, only being ‘considered intermittently’ (2) despite interviews with those close to the Green Party of Northern Ireland having been collected for the book (8).

In conclusion, Dennison offers some interesting quantitative analysis and direct insight into the Green parties’ inner workings. The elite interviews featured in the early chapters of the book are particularly interesting, both in terms of their narrative qualities and because the number and variety of interviews are quite impressive. However, some aspects of the book’s structure and style could be improved to make the text more accessible and compelling for readers. The book might also be considered a victim of unfortunate timing. Due to the surprise General Election of 2017, the tone of politics in Great Britain has already changed in ways which merit new exploration. As the public’s perceptions of the UK’s two largest political parties have shifted, so too has the position of the Greens. Nevertheless, this book provides a useful point of departure for future research on the Greens and their place in British politics.

Erica Frazier has recently obtained a joint PhD in political science under the direction of Prof. John Barry at Queen’s University Belfast in Northern Ireland and Prof. Karin Fischer with the REMELICE laboratory at the Université d’Orléans, France. Her research interests include political economy, green and labour politics and political discourses, cultures and movements in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Read more by Erica Frazier.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Find this book:

Find this book:

1 Comments